Summary:This article highlights ICU safety challenges, emphasizing structured handoffs and infection prevention as critical strategies to reduce patient harm. Evidence-based communication protocols and perioperative infection control bundles are central to improving ICU outcomes.

Intensive care units (ICU) emerged in the 1950s to localize the knowledge and resources needed to treat patients with respiratory failure. This care concept was effective, and ICUs have become ubiquitous in hospitals throughout the world. There has always been a close relationship between anesthesia professionals and the specialized field of critical care which has developed alongside the evolution of ICUs. Many hospitals have more than one ICU, which allows for sub-specialization in critical care. Outside of operating rooms and emergency departments, ICUs are the locations for treating our sickest patients, especially those suffering from shock, respiratory failure, and other life- or limb- threatening illnesses.

While not all anesthesia professionals practice intensive care, some do. The frequent movement of patients back and forth between operating rooms, procedural areas, and the ICUs makes critical care practice relevant to anesthesia professionals. As an example, adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is an all-too-common cause of respiratory failure in the ICU with a high associated mortality. The Acute Respiratory Management in ARDS (ARMA) trial, published in the year 2000, changed the paradigm of respiratory care to emphasis the protective effects of low tidal volume ventilation.1 Since the adoption of low tidal volume ventilation, the incidence and mortality of ARDS have both been declining.2 Low tidal volume ventilation prevents ventilator-induced lung injury by “dosing” tidal volumes using a formula based on the patient’s ideal body weight. Higher tidal volumes have been found to increase inflammation even in uninjured lungs.3 The practice of low tidal volume ventilation has transferred, although slowly, from the ICU to the operating rooms. Lung injury from large tidal volume ventilation is preventable. The story of lung protective ventilation shows that we can embrace practice changes to reduce preventable harm.

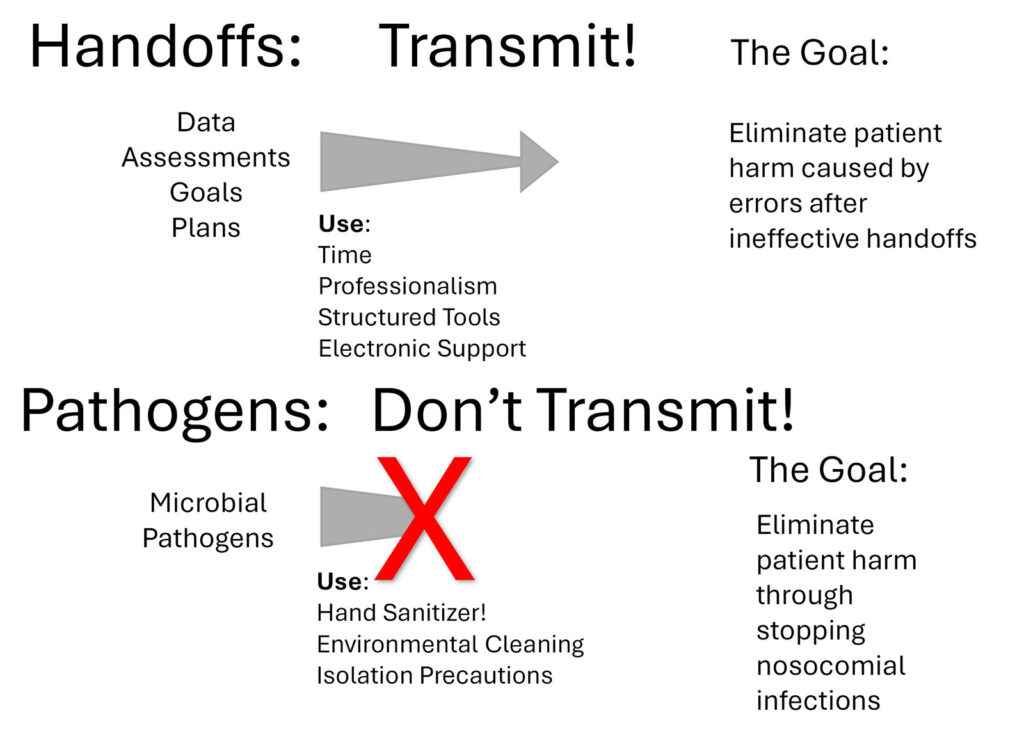

The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) has been inspiring anesthesia professionals to eliminate preventable patient harm since 1985. As we mark the 40th anniversary of the APSF, let’s extend its vision to eliminating patient harm in ICUs as well. Two patient safety frontiers for ICU patients are highlighted here: information sharing during handoffs and preventing the transmission of pathogens (Figure 1). These are complex areas where our knowledge is still growing, but research exists prompting us to act in order to prevent patient harm.

HANDOFFS

Handoffs between ICU professionals occur regularly. Shorter duty periods in the ICU have reduced sleep deprivation but increased the number of handoffs between team members working in the ICU. Additionally, ICU patients often transition to the care of non-ICU teams for surgery, procedures, and diagnostic tests. This creates additional handoffs both when a patient leaves and returns to the ICU. Managing the flow of information during these handoffs is an ongoing challenge. Hemodynamic monitoring, imaging procedures, pharmacologically relevant genetic testing, medication administration history, and the patient’s own wishes and requests can result in a mountain of information. Transmitting even a portion of this information to providers is challenging and this communication gap can lead to errors. Adverse events in the ICU are common, and more than half of them may be preventable.4 A recent multicenter trial that compared the impact of extended duration duty shifts of 24 hours or more with shift work of among trainees in the ICU found that there were more medical errors in the shorter duration duty periods and more errors unit wide, hypothesizing that the increased number of handoffs is a contributing factor.5

Optimizing handoffs both during anesthesia care and for ICU patients remains an area of research. Synthesizing the relevant information to effectively support a transition of care can be difficult and time-consuming. In the ICU, structured handoff approaches such as using the I-PASS tool suggested by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality may be helpful.6 Successful handoffs between anesthesia professionals and ICU teams require time and attention and may benefit from the use of structured handoff tools. Electronic tools have been developed to facilitate information transfer during transitions of care.7,8 Perhaps more important than the format of the handoff is the culture of excellent attention to detail that should be displayed during each handoff. The Multicenter Handoff Collaborative (MHC) is supported by the APSF as a special interest group to research, educate, and promote safe handoffs and has resources for the implementation of perioperative handoff initiatives.

The frontier for patient safety in handoffs of care in the ICU involves clinicians both recognizing the importance of excellent communication and utilizing the appropriate tools to ensure that a successful transition is completed. Even with advancements in computer technology providing new tools to process and present patient information, anesthesia and ICU team members are essential to successful patient handoffs.

PREVENTING PATHOGEN TRANSMISSION

While the ICU concept localizes critically ill patients to optimize patient care from specialized teams, it also creates an environment for potential pathogen transmission. While many patients come to the ICU to receive treatment for life-threatening infections, others develop nosocomial infections in the ICU that become life-threatening. Most of these nosocomial infections are preventable. Understanding the serious infectious risks for ICU patients and tools that are available to prevent nosocomial infections are the responsibility of all professionals who provide care to critically ill patients inside and outside of the ICU.

The challenges of pathogen transmission in the ICU mirror those in the operating room. Multidrug resistant pathogens are of particular concern in the ICU environment. In addition to usual modes of transmission, bacteria with antibiotic resistance may develop other characteristics, like biofilm creation, which allow them to survive on environmental surfaces longer than expected. A threshold of contamination of 100 colony forming units of any bacteria recovered from highly contacted surfaces in the ICU environment has been associated with the detection of major bacterial pathogens on that surface.9 Once these bacteria establish a reservoir in an area that is touched frequently, like the bed-rail in the ICU or the adjustable pressure-limiting valve in the operating room, these bacteria will continue to spread to both providers and patients until effective decontamination occurs.

Many of the same interventions that generate life-saving care in the ICU also produce opportunities for pathogens to create new infections. Vascular access catheters, including central lines and mechanical circulatory support access points, urinary drainage catheters, endotracheal tubes, and surgical or traumatic wounds are all susceptible to nosocomial infections. Often, it is the hands of the health care providers that directly cause the transmission of these pathogens.

Basic bacterial identification can reveal which pathogens are causing a particular infection, but they do not suggest a pattern of movement or transmission. After all, everyone has some bacteria on their skin. Research using bacterial genome analysis of bacterial populations contaminating anesthesia work environments and the hands of anesthesia professionals has shown that transmission of pathogens does occur in the operating room.10 Similar research in the ICU has shown that poor hand hygiene plays a crucial role in the transmission of pathogens, leading to health-care-associated infections (HAIs).11

Methods for preventing the spread of pathogens are well defined in the medical literature and enabled by tools already at our disposal. Such methods for anesthesia and ICU professionals include frequent utilization of alcohol-based hand sanitizers, and attention to isolation requirements.12 The APSF Patient Safety Priorities Advisory Group for Infectious Diseases has recommended the use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer at least 4 times per hour while caring for patients in the ICU and at least 8 times per hour while providing care in the operating room.13

Since the introduction of ICUs more than 70 years ago, there have been dramatic improvements in the life-saving interventions that can be provided. There have been consistent improvements in mortality associated with the treatment of respiratory failure and shock. While improvements in these areas continue to be sought after, there is also an urgent need to make progress in the areas of handoffs, and prevention of transmission of nosocomial pathogens. If health care members are provided the necessary information during a handoff they can make the best decisions, and our patients will have better outcomes. When nosocomial infections are prevented, patient outcomes will also improve. Our goal should be to transmit optimal information during handoffs and not transmit pathogens during patient care.

REFERENCES

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, Brower RG, Matthay MA, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301-8.PMID: 10793162

- Hendrickson KW, Peltan ID, Brown SM. The epidemiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome before and after coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(4):703-716. PMID: 34548129

- Pinheiro de Oliveira R, Hetzel MP, dos Anjos Silva M, et al. Mechanical ventilation with high tidal volume induces inflammation in patients without lung disease. Crit Care. 2010;14(2):R39. PMID: 11847522

- Martins NRS, Martinez EZ, Simoes CM, et al. Analyzing and mitigating the risks of patient harm during operating room to intensive care unit patient handoffs. Int J Qual Health Care. 2025;37(1). PMID: 39699203

- Landrigan CP, Rahman SA, Sullivan JP, et al. Effect on patient safety of a resident physician schedule without 24-hour shifts. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2514-2523. PMID: 32579812

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Tool: I-PASS. July 2023. Available at: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/curriculum/communication/tools/ipass.html. Accessed 6/27/2025.

- Shah AC, Oh DC, Xue AH, et al. An electronic handoff tool to facilitate transfer of care from anesthesia to nursing in intensive care units. Health Informatics J. 2019;25(1):3-16. PMID: 29231091

- Benton SE, Hueckel RM, Taicher B, Muckler VC. Usability assessment of an electronic handoff tool to facilitate and improve postoperative communication between anesthesia and intensive care unit staff. Comput Inform Nurs. 2020;38(10):500-507. PMID: 31652138

- Koff MD, Dexter F, Hwang SM, et al. Frequently touched sites in the intensive care unit environment returning 100 colony-forming units per surface area sampled are associated with increased risk of major bacterial pathogen detection. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e68317. PMID: 39350803

- Loftus RW, Dexter F, Parra M, et al. The importance of the detection of staphylococcus aureus strain characteristics associated with perioperative transmission of antibiotic resistance. Cureus. 2025;17(4):e81885. PMID: 40342447

- Clancy C, Delungahawatta T, Dunne CP. Hand-hygiene-related clinical trials reported between 2014 and 2020: a comprehensive systematic review. J Hosp Infect. 2021;111:6-26. PMID: 33744382

- Tschudin-Sutter S, Pargger H, Widmer AF. Hand hygiene in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(8 Suppl):S299-305. PMID: 20647787

- Charnin JE, Hollidge M, Bartz R, et al. APSF Newsletter. 2022;37(3):103-106. https://www.apsf.org/article/a-best-practice-for-anesthesia-work-area-infection-control-measures-what-are-you-waiting-for/ . Accessed 6/27/2025.