Luer Fittings

Named after German instrument maker, Hermann Luer, Luer fittings are among the earliest medical fittings designed to provide leak-free connections between syringes and needles and maintain a continuous lumen for fluid flow. The mated fittings are cone-shaped with a 6% taper. When pressed together, the compression of the inner wall against the outer wall of the taper is designed to produce a leak-free connection. The use of the Luer connection is most associated with vascular access; however, it has been used for other medical applications as well (e.g., enteral connections and pneumatic connections). To eliminate hazardous, often fatal, cross connections, the recently developed ISO 80369 standard Luer fitting limits its use to vascular applications only.

Luer fittings are manufactured most commonly from plastic; however, they can also be made from glass or metal. The new standard for intravascular connectors, ISO 80369-7, imposes restrictions regarding the softness of plastic fittings to help ensure that the connection will not deform under pressure.

Types of Luer Fittings/Connections

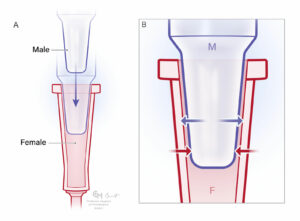

Figure 1: A) Male and female Luer taper connectors unengaged. B) Luer Taper connectors engaged to form a leak-free connection. Arrows indicate compressive forces between the inner and outer walls of the taper. The connection is secured by the combination of compressive forces and friction between the contact surfaces. Note that dry connections are typically less likely to disconnect than when the taper surfaces are wet.

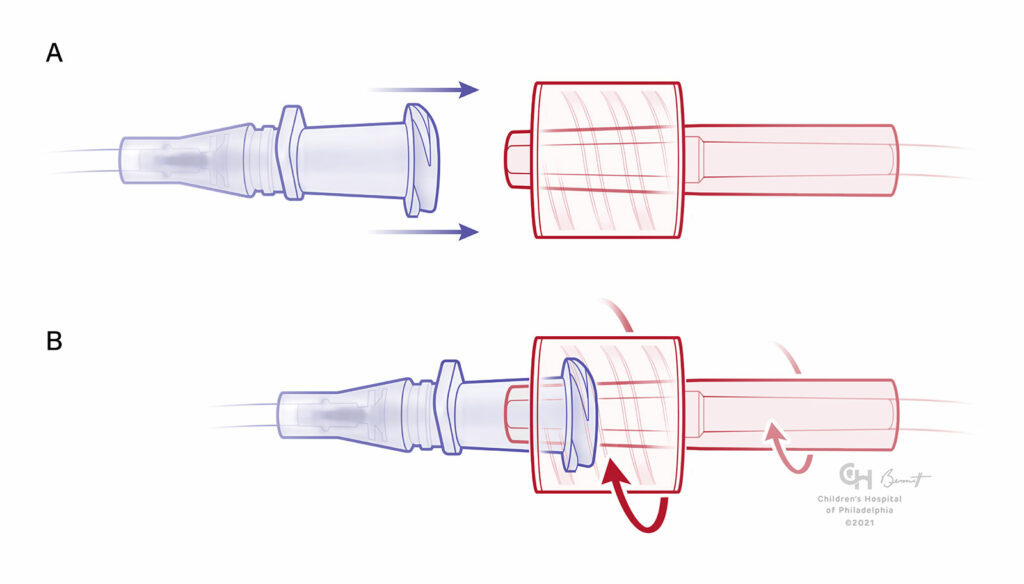

The Luer Taper fitting often referred as the Luer Slip, is the original design and relies solely on the compression forces and resulting friction between the opposing conical surfaces to maintain a leak-free connection (Figure 1). Accidental separation is possible with this design whenever pulling force is inadvertently applied to the connection. As a way to mitigate accidental separation, Luer-lock fittings were developed and are comprised of a male taper with an associated threaded “skirt” and a female taper having flanges to engage the threads called “lugs” (Figure 2). When the two fittings are screwed together, the tapered surfaces are compressed in the same manner as the taper connection; however, with the addition of the threaded coupling, the connection cannot be simply pulled apart.

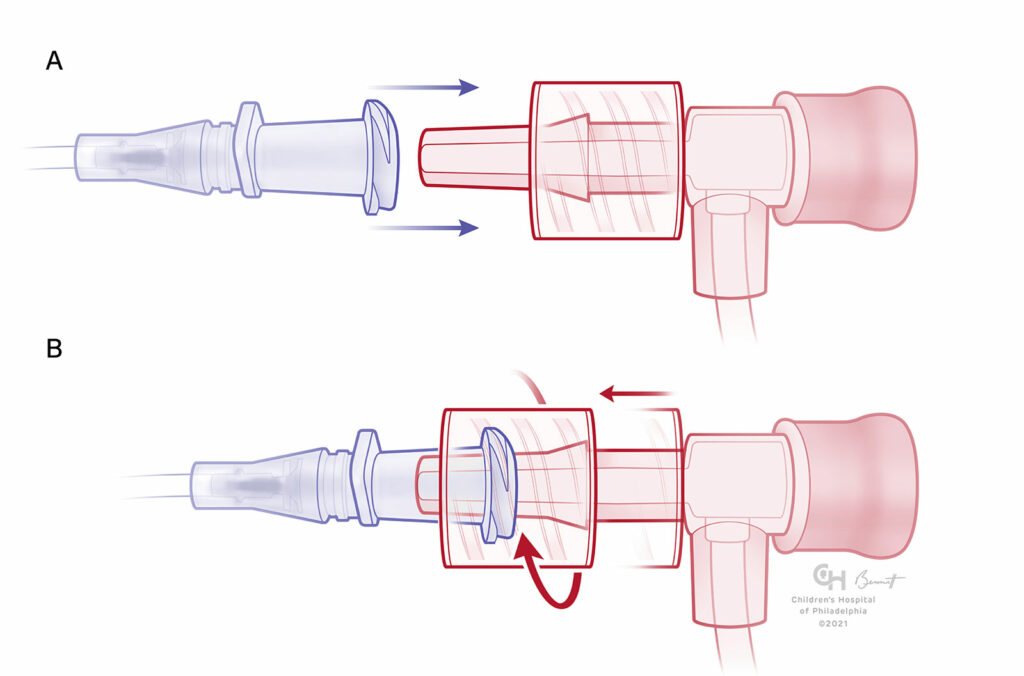

There are two versions of the Luer-lock connector. The male Luer-lock fitting may have a “fixed” skirt in which the skirt and Luer taper are a single piece or it may have a “swivel” skirt in which the skirt and taper are separate pieces (Figures 2 and 3). The swivel skirt allows for the taper fit to be engaged and then secured with the skirt without imparting any twist to the intravenous tubing.

Figure 2: A) Male Luer-Lock with fixed-skirt and receiving female component unengaged. B) Fixed-skirt male component “locked” in place. Note that a fixed-skirt connector can put a twisting force (torque) on any tubing attached to the connectors.

Figures 3: A) Male Luer-Lock with swivel-skirt and receiving female component unengaged. B) Swivel-skirt male component engaged. Note that the swivel skirt allows the Luer taper to be engaged first and then secured with the skirt to avoid any twisting force on the attached tubing.

Luer Misconceptions

Despite the name, Luer-lock, these fittings do not make a true “locking” connection. When the connection is made, there is no associated latching mechanism. Furthermore, the skirt does not provide additional leak protection. Luer-lock connections are also vulnerable to unintended separation; while not easily pulled apart, they are subject to accidental unscrewing. The Luer-lock connection requires the skirt to be unscrewed to separate the tapers. With the proliferation of bulkier Luer components, the opportunity for accidental unscrewing has increased due to the greater torque (i.e., leverage) that can be applied to the Luer-lock connection. For example, a syringe connected to a three-way Luer stopcock can easily loosen the luer-lock connection perpendicular to the syringe. ECRI has adopted the term “Luer leverage” for such circumstances. Because the skirts have very coarse threads, it only takes ~¼ turn to loosen the connection between the male and female tapers.

As an example of the ramifications of Luer leverage, a patient died from hemorrhage and air embolism attributed to a jugular sheath disconnection from a hemostasis valve with an integral 6-inch sideport connected to the sheath using a Luer-lock connection. At the time the sheath was placed, its hub was sutured to the patient’s skin, preventing the female hub from rotating. At some point, the IV tubing connected to the hemostasis valve sideport tubing was pulled, applying sufficient torque to unscrew the Luer-lock which led to exsanguination from the sheath and entrainment of air.

Complications of Luer Connection due to Partial or Total Separation

Luer separations result in four types of complications that can happen separately or in combination: infection, blood loss, air embolism, and medication leakage at the connection. Blood loss and/or air embolism will be the focus of this section. Separations can be complete or partial. Partial separations occur when the components appear to be connected, but are not tight enough to prevent a leak, and can be difficult to detect.

All that is required for blood loss or air embolism to occur is a leak between the vascular system and the atmosphere, and a pressure gradient favorable for bleeding or air entrainment. The degree of blood loss or air ingress is proportional to the magnitude of the pressure gradient, the resistance in the leak and the length of the conduit. When the pressure in the tubing lumen is higher than ambient air pressure, blood can leak out of the Luer connection. Conversely, if the pressure in the lumen is lower than ambient air pressure, air can potentially enter the bloodstream. Loss of blood or ingress of air resulting from naturally occurring pressure gradients are passive events. When pressure or vacuum applied by devices such as syringes and pumps are involved, these are active events, and pressure gradients are generally much greater than naturally occurring pressures. For example, during a Luer disconnection of a hemodialysis catheter blood loss can occur at a very high rate.

Luer Connection Management

Despite the fact that the Luer-Lock is not a truly secure connection, there are strategies for use that can mitigate the potential for complications from leaks or separations. This section will focus on mitigation strategies for Luer-lock connections, but the majority apply to the Luer taper connections as well.

Making the Connection(s)

- When possible, make the connection using dry male and female Luer components. Since the connection integrity depends on the friction between the male and female Luer taper, dry fittings will be more secure than wet fittings (i.e., those having solution or blood on/in the tapers or the skirt). Even so, wet connections are often unavoidable (or even preferable), and can be completed without leaks when done properly.

- Luer fittings should only be tightened by hand. Use of grasping instruments should be avoided because the fitting can be damaged, increasing the potential for leak or air ingress. Grasping instruments can be used with caution to separate Luer fittings when/if the connection is too tight to separate by hand.

- Avoid making Luer connections with fittings made from different materials (i.e., metal to plastic).

- Be careful not to cross-thread the male Luer skirt threads on the lugs of the female taper. Because the male taper extends beyond the end of the threaded skirt, the tapers engage before the skirt and help to maintain the alignment of the fittings. When using the swivel skirt design, retracting the skirt and making the taper connection first will also help with alignment.

- Finally, make no more connections than necessary. The number of connections is directly proportional to the risk of an unwanted separation.

Maintaining the Connection(s)

Once the Luer connection is made, it needs to be protected from forces that can separate the connections. Such forces can be mitigated in following ways:

- Maintain some slack in the lines near Luer connections to indwelling catheters.

- Run lines in a manner that prevents them from being snagged when moving the patient, surrounding equipment or other persons. Note that too much slack increases this risk.

- Avoid Luer leverage by minimizing the use of devices that extend perpendicularly from the adjacent Luer connections. To the degree possible, orient such devices so that if they are snagged or lines connected to them are pulled, they will not unscrew the adjacent Luer-lock.

- Unused Luer ports should be maintained with solid (non-vented) Luer caps. Stopcocks and pinch clamps should not be relied on as the sole means of preventing leakage or air ingress at unused Luer fittings.

Monitoring the Connection(s)

The following points are useful guidance based upon experience with accident investigation.

- To simplify monitoring Luer connections, avoid locations that conceal the connection and/or make the connection difficult to access, such as under bed clothes or beneath drapes. In particular, never cover any connections to extracorporeal circulation equipment which may fail to detect disconnections until potentially life threatening blood loss or air ingress has occurred.

- Inspect the lines proximal and distal to the Luer connection for potential entrapment that could permit separation forces to be applied to the connection. For example, drooping lines that could be snagged by foot traffic around the patient.

- Inspect IV lines downstream from their connections for the presence of air segments. When air is detected, the tightness and condition of the upstream connections should be assessed.

- Inspect dressings that cover Luer connections for wetness or blood. When possible, use clear dressings that permit direct observation of the connection.

Like any medical device, the potential for patient harm from a Luer connection can be reduced by understanding the design considerations, potential for injury, and strategies for proper use. Following the guidance provided here should reduce the potential for a Luer-related adverse event or outcome.