Aubrey Samost-Williams, MD, MS; Jeffrey Cooper, PhD; Arney Abcejo, MD; Elizabeth Rebello, MD, FASA, FACHE

Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Vol 40 No 3 Oct 2025

The APSF has spent four decades advancing medication safety in anesthesia through research, education, system design, and advocacy. Progress includes labeling standards, technology adoption, and cultural changes that continue to reduce preventable harm.

As anesthesia professionals, improving patient safety can easily feel like running on a treadmill—each day we jump on, sprint forward, and as tired as we may get, it can seem that we are making no forward progress. However, as we celebrate 40 years of the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF), we hope to show you that we should also celebrate 40 years of steady progress towards the goal of zero preventable harm to patients from medication administration.

As anesthesia professionals, improving patient safety can easily feel like running on a treadmill—each day we jump on, sprint forward, and as tired as we may get, it can seem that we are making no forward progress. However, as we celebrate 40 years of the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF), we hope to show you that we should also celebrate 40 years of steady progress towards the goal of zero preventable harm to patients from medication administration.

Since its founding in 1985, the APSF has consistently prioritized medication safety in anesthesia practice. The APSF identified medication errors as a significant patient safety concern early in its history. In 1987, the APSF Newsletter addressed issues related to look-alike medication errors.1,2 Over the years since, the APSF Newsletter has published over 140 articles on medication safety, emphasizing the importance of standardizing drug concentrations and equipment to reduce confusion and errors.3 Through the APSF Newsletter, the organization has disseminated research findings, best practices, and expert recommendations to mitigate medication errors in the perioperative setting.

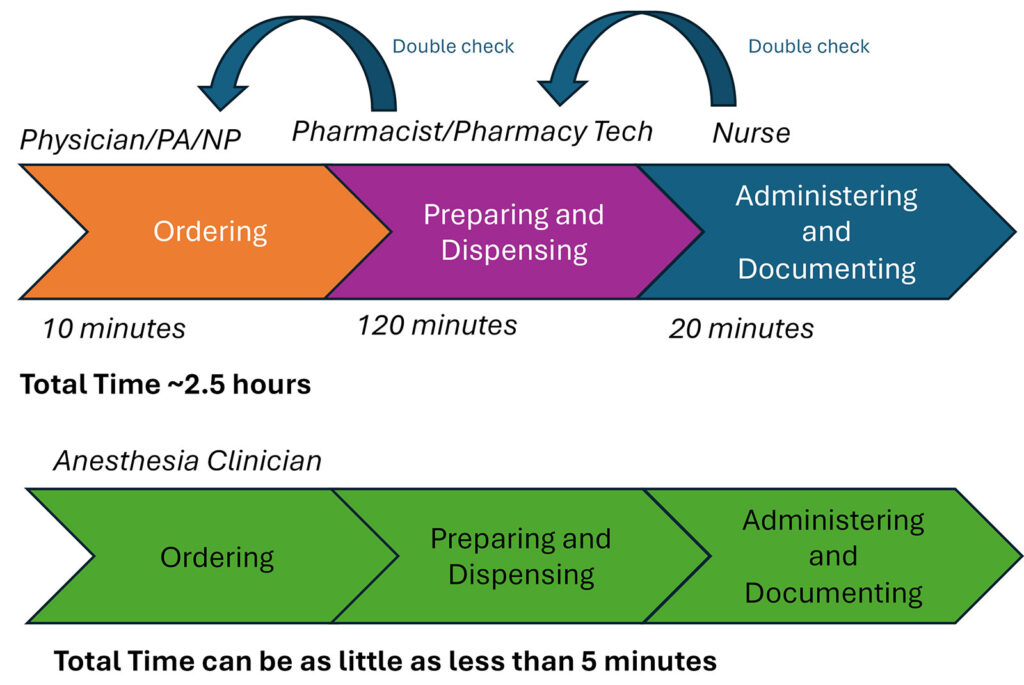

Medication administration in the operating room is a unique and challenging process (Figure 1). Nowhere else in the hospital does the same person (1) select the medication and dose, (2) prepare the medication, and (3) administer the medication. Elsewhere, these three functions are done by (1) the physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner, (2) the pharmacist or pharmacy technician, and (3) the bedside nurse. These independent team members provide monitoring and double-checking throughout the process. In the operating room, these same three tasks are done by a single anesthesia professional and are typically done quickly, as seconds count in acute life-saving situations.

Figure 1: Comparison of the inpatient medication administration process and the OR medication administration process. Timing estimated from Bhansali and colleagues,7 Yen and colleagues,8 and internal pharmacy data.

Early medication safety efforts focused on the behavior of the anesthesia professional, with efforts to improve safety typically through educational programs encouraging close reading of labels and design work to make those labels more readable. As safety science matured, the emphasis on attentiveness was recognized as inadequate for prevention of medication errors. Rather, emphasis was refocused on forcing functions and creating feedback mechanisms and constraints. This need to shift the paradigm in thinking of medication errors led to the 2010 APSF Stoelting Conference focused on medication safety.

2010 APSF STOELTING CONFERENCE ON MEDICATION SAFETY

This conference focused on creating an expert consensus-based framework for moving medication safety beyond admonishing clinicians to pay more attention, instead creating the Standardization, Technology, Pharmacy/Prefilled/Premixed, and Culture (STPC) framework (Table 1).4

Table 1: 2010 Recommendations and STPC Framework.

| Standardization |

|

| Technology |

|

| Pharmacy/ Prefilled/ Premixed |

|

| Culture |

|

STPC: Standardization, Technology, Pharmacy/Prefilled/Premixed, and Culture

2018 APSF STOELTING CONFERENCE ON MEDICATION SAFETY

In 2018 the APSF annual conference again focused on medication safety. This conference continued some of the same themes from 2010, such as an emphasis on standardization and human factors, but expanded to further consider new challenges in medication safety, including drug safety profiles and drug shortages (Table 2).5

Table 2: 2018 Stoelting Conference Medication Safety Recommendations.

| Drug Safety Identify and promote potentially safer anesthetics |

|

| Drug Shortages Share information, simplify ordering, and establish contingency plans |

|

| Reducing Drug Administration Errors Standardize procedures and doses, carefully document administration, and simplify preparation |

|

| Standardization and Innovation Collaborate across specialties and establish consensus for refined standards |

|

ACTIVITIES BETWEEN MEETINGS

While the Stoelting Conferences on medication safety have provided large pushes and paradigm shifts in our collective work on promoting safer use of medications, it would be remiss to ignore the hard work that has come in between. Here are a few recent efforts and wins to highlight:

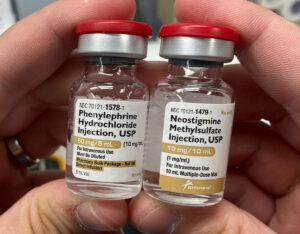

- In 2018, following the Stoelting Conference, APSF began hosting the Look-Alike Drug Vials Gallery (Figure 2). The stark visualizations of the risks to our patients has helped us form industry partnerships to begin to tackle these challenges.

- In 2021, APSF formed Patient Safety Priority Advisory Groups, one of which focused on medication safety. This group included a diverse membership of key stakeholders, including anesthesiologists, certified registered nurse anesthetists, anesthesiologist assistants, anesthesiology residents, pharmacists, perioperative nurses, a lawyer specializing in medical malpractice, and industry partners representing pharmaceutical and device companies. Currently, the group is working on implementing the recommendations arising from the recent 2024 Stoelting Conference.

- APSF reported on a series of medication errors involving intrathecal administration of tranexamic acid (TXA).6 Through advocacy and industry partnership, they were able to promote the availability of TXA in infusion bags and the reduction of the use of TXA vials in the perioperative environment.

- Additionally in 2024, APSF partnered with the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) to investigate increased reports of coring of vial tops when preparing medications for administration and released an alert to anesthesia professionals nationwide in the US.

- In 2023–25, APSF helped advocate for the reinstatement of American Society for Testiing and Materials (ASTM) standard D4774, which standardizes the color-coding used on labels for different medication classes. While this sounds esoteric, APSF’s lobbying for these industry-wide standards ensures that the concerns of practicing anesthesiology professionals are incorporated into the equipment that we work with every day in the OR.

2024 APSF STOELTING CONFERENCE: TRANSFORMING ANESTHETIC CARE: A DEEP DIVE INTO MEDICATION ERRORS AND OPIOID SAFETY

Finally, in 2024 the APSF Stoelting Conference again focused on medication safety. As in 2018, the unique context and challenges of the moment brought a different perspective on the problem of medication safety.

The intervening six years since the prior Stoelting Conference focused on medication safety brought about significant advances in our understanding of the harms of opiates, not just in the immediate postoperative period, but even beyond, as we have witnessed communities ravaged by the epidemic of opiate addiction. With the rise of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols with their multimodal pain management approach and a debate over the proper role for and dosing of perioperative opiates, there was a robust discussion about how to use opiates wisely.

Additionally, we are witnessing the rise of artificial intelligence to a level not imaginable just six years ago. We now have the ability to move past simple electronic double-checks of medications, where we might scan the label and have the software confirm that the patient is not allergic to it. Now we can imagine clinical decision support tools that can help determine whether the medication to be administered is a good choice given the patient’s current physiological state. This type of technology opens new avenues for promoting safety, while also raising new challenges and new safety risks.

Despite these new technologies and new challenges, this meeting also recognized that many of the challenges being faced in medication safety have been present since the founding of APSF 40 years ago. We continue to face challenges with basic syringe swaps and medication dosing errors due to differing concentrations. The prior two conferences approached these challenges with calls for work grounded in human factors and system safety principles. Despite recognizing the importance of improving these processes and identifying best practices for medication safety, there exists a significant implementation gap.

In a preconference poll prior to the 2024 APSF Stoelting Conference, attendees, a group self-selected for interest and leadership in medication safety (n=69), reported that fewer than half of their institutions had fully implemented practices such as standardized drug labeling, prefilled syringes for at least three unique medications, or standardized medication drawers for automated dispensing cabinets or medication trays. Respondents reported top standardization strategies for medication safety should include syringe label design, color-coded syringe labels, standardized concentrations, prefilled syringes, and standardized medication storage locations during surgery. In addition, preoperative assessments, postoperative monitoring, and research into nonopioid alternatives are measures that should be prioritized to prevent opioid-related harm.

Therefore, pivoting the focus on the relatively new field of implementation science may better identify the barriers to implementing these medication safety best practices. Recommendations this year will continue to encourage the practices highlighted in prior years, but the work products will aim to help institutions successfully implement measures that we know can save lives.

CONCLUSION

Forty years is a long time. Our medication administration has evolved from copper kettles to variable bypass vaporizers, and from relatively few medication options to an entire automated medication dispensing cabinet. But just as our care has evolved, our medication safety practices have evolved from education and policy interventions to strategies incorporating human factors, cutting-edge technology, systems engineering, and implementation science. There has been an increased focus given to systems issues and less blame on an individual. Through work in this field, we can safeguard our communities and patients by developing into perioperative clinicians with a lens that broadens beyond the operating room and PACU. Much of this progress has been made collaborating as a team with pharmacists, nurses, institutional leadership, industry, safety organizations, standard-setting organizations, and federal agencies. It has been an exciting journey over the past 40 years, and we look forward to seeing what the next 40 years will bring.

REFERENCES

- Brauer, Rendell-Baker L. Fatal potassium error. APSF Newsletter. 1987;2(2). https://www.apsf.org/article/fatal-potassium-error/ Accessed June 30, 2025.

- Rendell-Baker L. Better labels will cut drug errors. APSF Newsletter. 1987;2(4). https://www.apsf.org/article/better-labels-will-cut-drug-errors/ Accessed June 30, 2025.

- APSF Newsletter Archives—Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. https://www.apsf.org/apsf-newsletter/archives/ Accessed June 30, 2025.

- Eichorn J. APSF hosts Medication Safety Conference. APSF Newsletter. 2010;25(1). https://www.apsf.org/article/apsf-hosts-medication-safety-conference/ Accessed June 26, 2025.

- Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Recommendations of the four work groups at the 2018 APSF Stoelting Conference on Medication Safety. https://www.apsf.org/medication-safety-recommendations/ Accessed June 26, 2025.

- Lefebvre PA, Meyer P, Lindsey A, et al. Unraveling a recurrent wrong drug-wrong route error—tranexamic acid in place of bupivacaine: a multistakeholder approach to addressing this important patient safety issue. APSF Newsletter. 2024;39:37, 39–41. https://www.apsf.org/article/unraveling-a-recurrent-wrong-drug-wrong-route-error-tranexamic-acid-in-place-of-bupivacaine/ Accessed June 30, 2025.

- Bhansali P, Birch S, Campbell JK, et al. A time-motion study of inpatient rounds using a family-centered rounds model. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3:31–38. PMID: 24319833.

- Yen PY, Kellye M, Lopetegui M, et al. Nurses’ time allocation and multitasking of nursing activities: a time motion study. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2018;1137–1146. PMID: 30815156.