Department of General Anesthesiology

Cleveland Clinic Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Professor of Anesthesiology

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University

Cleveland, Ohio

University of Florida College of Medicine

Gainesville, Florida

President-Elect

Society for Airway Management

Director, Pediatric Anesthesia Research

Department of Pediatric Anesthesiology

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago

Professor of Anesthesiology

Northwestern University

Chicago, Illinois

Vice Chair for Clinical Affairs

Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care

The University of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois

Chief, Division of Neuroanesthesia

Department of Anesthesiology

Montefiore Medical Center

New York, NY

Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital

University College London Hospitals

Honorary Senior Lecturer

University College London

London, United Kingdom

President, Difficult Airway Society

University of Toronto

Staff Anesthesiologist

Toronto Western Hospital

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

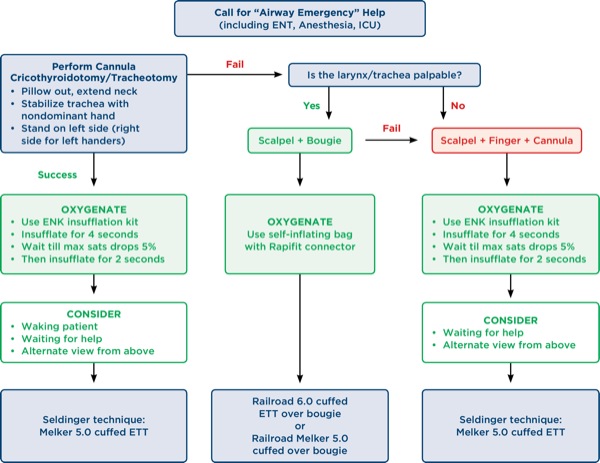

Dr Berkow: Several studies have reported increased complications with percutaneous cricothyroidotomy methods. I think there is a bigger issue here—the importance of training and practice for clinicians to perform front-of-neck access (FONA). Two editorials, one by Timmermann et al2 and the other by Booth and Vidani,3 discuss the human factors aspect of FONA. Both editorials discuss the concept that anesthesiologists are more adept and comfortable with Seldinger technique procedures as opposed to scalpel techniques, since we perform these types of procedures regularly (ie, central or arterial line placement), and that “psychological preparedness” also may play a role in a clinician’s willingness to perform a surgical procedure. These human factors may be a reason why often there is a delay in performing a FONA technique.

Dr Doyle: Needle cricothyroidotomy in conjunction with transtracheal jet ventilation (TTJV) is sometimes advocated as a last-ditch option to avoid death in a CICO situation. In TTJV, oxygen is injected percutaneously under high pressure (eg, 20 psi) via a narrow-bore, high-resistance cannula, typically using a 12- or 14-gauge intravenous catheter or a purpose-built catheter, such as that made by Cook Medical. Unfortunately, this technique of ventilation is associated with a number of safety concerns based on the fact that expiration of the injected gas in this setting must take place via the nose or mouth since passive gas expiration via the transtracheal catheter is minimal. As a result, in situations where complete airway obstruction exists and no gas egress pathway exists, repeated injections of oxygen will cause pressure build-up that may produce barotrauma events, such as pneumothorax or subcutaneous emphysema, which lead to hemodynamic deterioration or even full cardiac arrest.

In a meta-analysis by Duggan et al,4 44 studies involving 428 procedures were reviewed. The authors found that device failure occurred in 42% of CICO emergencies, with barotrauma occurring in 32% of CICO emergencies. In some cases, TTJV-related subcutaneous emphysema made subsequent attempts at airway management much more difficult. The authors concluded that “TTJV is associated with a high risk of device failure and barotrauma in the CICO emergency” setting, and “recommendations supporting the use of TTJV in CICO should be reconsidered.”

Duggan et al4 are not alone in being concerned that TTJV via cannula cricothyroidotomy is potentially perilous. The NAP4 study1 offers the following commentary:

“There was a high failure rate of emergency cannula cricothyroidotomy, approximately 60%. There were numerous mechanisms of failure and the root cause was not determined; equipment, training, insertion technique, and ventilation technique all led to failure. In contrast, a surgical technique for emergency surgical airway was almost universally successful. The technique of cannula cricothyroidotomy needs to be taught and performed to the highest standards to maximise the chances of success, but the possibility that it is intrinsically inferior to a surgical technique should also be considered. Anaesthetists should be trained to perform a surgical airway.”

The results of the NAP4 study and the experience of others have led many experts to recommend the abandonment of cannula cricothyroidotomy methods in favor of using a surgical approach. The Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults (Freck et al)5 note that “scalpel cricothyroidotomy is the fastest and most reliable method of securing the airway in the emergency setting,” and emphasize that “whilst a wire-guided technique may be a reasonable alternative for anaesthetists who are experienced with this method, the evidence suggests that a surgical cricothyroidotomy is both faster and more reliable.”

Dr Jagannathan: The NAP4 study1 has taught us that percutaneous transtracheal ventilation has poor success rates and is an unreliable approach to emergency airway rescue. Given these findings, needle cricothyroidotomy with percutaneous transtracheal ventilation should no longer be taught. Rather, the efforts for emergency FONA should focus on a reliable, universal, and standardized approach (eg, scalpel bougie technique). Percutaneous transtracheal ventilation via a narrow- and/or wide-bore cannula has major drawbacks, including:

- failure of the cannula caused by kinking, malpositions, or displacement;

- a significant risk for barotrauma, as cannula techniques require a high-pressure oxygen source; and

- inefficient ventilation.

An even bigger issue is the differences between various cannula kits and oxygen sources (eg, ENK flow modulator, jet ventilator, and breathing bag) available for use. This makes standardization of training difficult for FONA since standardized equipment may not be universally available. I agree with the Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines5 that there is convincing evidence suggesting that a surgical cricothyroidotomy is faster, more reliable, and easier to teach and implement as a standardized approach for emergency FONA.

There are 3 conclusions I reach from these findings:

- We cannot rely on small- or large-bore cannulae for eFONA.

- Anesthesia providers should receive training with scalpel-based FONA techniques, including the “scalpel-bougie-tube” approach. In this sequence, a scalpel is used to incise the skin and cricothyroid membrane. Then a bougie or other tracheal introducer is placed through the hole into the trachea and a small endotracheal tube (ETT) is advanced over the introducer. This training can be achieved using anatomic models, cadavers, and/or larynx specimens from animals such as pigs or sheep.

- Despite the strengths of the NAP4 study,1 these findings are prone to confounding. It is impossible to determine if the success of the larger tubes was due to the devices or the fact that surgeons were the ones placing the devices. Regardless, anesthesia providers should receive training in and maintain skills for establishing FONA. The face value of the scalpel-bougie-tube technique is very high and is recommended by many surgeons and airway experts.

Dr Osborn: I don’t have a problem teaching the technique of needle cricothyrotomy because most anesthesiologists are quite familiar and skilled with the Seldinger technique and more likely to employ it compared with a scalpel. Although I have only used it once in my career, I can see its usefulness in head and neck surgical cases where the airway is lost or fiber-optic intubation has failed. It must be employed early with appropriate equipment, such as the Melker kit (Cook Medical). Once the airway is established, the proper system for ventilation must be available. I am hoping to use the Ventrain system when it is approved in the United States because I think it will be very effective with needle cricothyroidotomy.

Dr Patel: The NAP4 study1 was a national audit in the United Kingdom documenting all serious airway complications in one year. Nothing of this sort had been undertaken prospectively on such a scale. The data showed when emergency airway rescue was required, anesthetists failed to insert and ventilate via a small-bore (needle cricothyroidotomy) 37% of the time. By contrast, a surgical airway with knife (scalpel) and tube was successful 100% of the time. There were differences in the time pressures for surgical airway and needle cricothyroidotomy, but multiple other studies have shown similar differences in success rates between needle cricothyroidotomy and surgical airway using scalpel and tube.

In the United Kingdom, the Difficult Airway Society came to the conclusion that despite many decades of teaching needle cricothyroidotomy when it was used in emergency airway rescue in the United Kingdom, it was failing more often than it was successful. Concerns with needle cricothyroidotomy were:

- misplacement,

- simplicity of use (multiple types and sizes, guidewire Seldinger techniques in high-stress states),

- experience with and understanding of high-pressure source ventilation through a small-bore cannula,

- placement with poor landmarks, and

- protection from aspiration.

The Difficult Airway Society considered it better to teach everyone a single technique with the greatest success in airway rescue—a scalpel-bougie-tube technique—than have multiple techniques with multiple equipment across the country. This is what is currently taught as the “baseline” airway rescue technique in the United Kingdom and what we would expect everyone to be familiar with. We have not stopped needle cricothyroidotomy use, but we do think if it is used, it should be by an expert in such techniques who have to ensure it is practiced by all staff in that hospital or region, including trainees who would be expected to be equally expert if they were to use the technique. The equipment must also be immediately available in every anesthesia location, and staff must also be familiar with a scalpel-bougie-tube technique if the needle technique fails.

Dr Wong: My short answer is yes. The NAP4 study1 indicated a nearly 100% success rate with 33 surgical cricothyroidotomies or tracheostomies performed by surgeons. In 25 cases where FONA was attempted by anesthesia, the success was about 40% to 60%. My interpretation of the success of FONA is primarily driven by the operator rather than the technique. Anesthesiologists are generally averse to using a scalpel, especially in a crisis. On the other hand, we are generally more familiar conceptually with a wire-guided Seldinger or the scalpel-bougie technique. In a Canadian anesthesiologists’ survey,6 given a CICO scenario, 39% chose wire-guided cricothyroidotomy, 28% selected narrow-bore cannula, 23% would defer to surgeons, 8% chose open surgical cricothyroidotomy, and 3% selected scalpel-bougie. Training and simulation are obviously important to improved success in real-life CICO situations. However, my bias is that anesthesiologists are much less reluctant to use a wire-guided Seldinger or narrow-bore cricothyroidotomy than an open surgical cricothyroidotomy. Anesthesiologists should be trained for 2 FONA techniques.

Dr Berkow: Mannequin-based studies have been widely used for airway research and have several advantages: They are less expensive, do not require informed consent, can be performed in a shorter period of time, and do not put actual patients at risk. However, the question is, can results obtained in a mannequin model be extrapolated to human subjects?

Schebesta et al7 compared the airway anatomy of several airway simulators and airway trainers with actual patients by performing CT scans on both groups and measuring several cross-sectional areas and volume parameters of the upper airway for similarity. They found that the pharyngeal airspaces of the mannequins were significantly different from actual patients.

Another concern related to the use of mannequin studies, which often use time to intubation or time to device insertion as a measurement, is whether it is appropriate to extrapolate these data points to human subjects. Two studies, for example, found significantly different success rates for supraglottic airway (SGA) insertion in mannequins compared with human subjects.8,9

Another argument for the use of mannequins is that a consistent intubating environment can be created, allowing for the creation of comparative data; yet actual patients are often unpredictable and variable! And I think everyone would agree that a plastic or silicone mannequin does not accurately simulate human tissue, and lacks blood or secretions.

Rai and Popat,10 in their editorial “Evaluation of airway equipment: man or manikin?” performed a literature search of mannequin studies of airway devices, and could not find a single study in which the authors followed up with a similar study in humans to validate their results. They declared, “It is time for serious researchers to move on to study patients.”10

On the positive side, mannequins and simulators are valuable tools for teaching familiarity with airway devices to providers before use on actual patients, and for communication and team training exercises without actual patient risk.

Dr Doyle: I frequently tell the trainees struggling with learning intubation using a mannequin that in real life, intubation is typically easier. In fact, some training courses, recognizing this fact, use the course participants themselves as human subjects for awake intubation!11,12 Also, remember that not all airway simulation mannequins are the same in terms of performance. For instance, Silby et al13 assessed 4 commercially available airway mannequins as simulators for insertion of the LMA Classic (Teleflex) and found great differences in performance. Jackson and Cook14obtained similar findings in studying other SGA devices. Finally, learning fiber-optic intubation need not start with an expensive mannequin. Appelboam and Snow15 have shown how one can make a simulated bronchial tree using 3/4-inch washing machine Y-pieces at very minimal cost. In the end, my take on this is that airway simulators are a great place to start with clinical airway training, but will never be as valuable as experience on real patients.

Dr Jagannathan: While mannequin studies may be suitable to teach, train, and acquire and assess skills by emulating rarely encountered clinical situations, mannequin studies have major drawbacks. Although a difficult airway mannequin may be useful for teaching and training purposes, the results observed from mannequin studies may not be translated to real-life clinical conditions. Certain variables, such as secretions and dynamic changes (reflex activation of the airway, light anesthesia, oxygen desaturations) are difficult to emulate, thereby limiting their clinical relevance.

Even high-fidelity simulation with better features cannot completely remove the sense of an artificial environment and may not be reflective of real clinical practice or behavior. The time pressure and stress experienced in actual clinical practice cannot be replicated and experienced during performances on a mannequin. Although these limitations exist, mannequins have been a valuable tool to train on and enhance clinical education. Situations exist where it may be unethical to perform a clinical trial or test experimental equipment on human subjects. In these situations, the use of mannequins and/or animal models becomes a more suitable study model; however, the translational value of a mannequin is highly questionable.

Dr Klock: Airway simulators, mannequins and trainers were developed to train people to improve performance of specific tasks. When they were developed, they intended to mimic the mechanics for mask ventilation and tracheal intubation. A 2012 study compared the airway dimensions of a series of patients with 2 popular airway trainers and 4 high-fidelity patient simulators. They found that none of the mannequins had anatomic dimensions that consistently replicated the sample of human subjects assessed.16 In addition to significant differences between human anatomy and the pharyngeal dimensions of the airway mannequins, “tissue fidelity” is a significant problem. The currently available mannequins do not simulate tissue coefficients of static and dynamic friction, secretions, compressibility, and range of motion in a convincing manner.

I believe that mannequins have an important role in education and training. They may be useful for specific studies of human behavior, learning, and performance in special circumstances, like limited access to the patient’s head or a simulated toxic environment. I do not believe that mannequins should be used to evaluate the efficacy of devices or to compare airway management techniques. Airway mannequins are great tools for training, but like any tool, they can be harmful if used for a purpose other than that for which they were designed.

Dr Osborn: I have never been a fan of mannequin studies, although I appreciate the difficulty of conducting clinical research in humans. They might be valuable to a certain degree in terms of ability to quickly learn a new skill, but performance of the device in a human that has secretions, reflexes, and variable anatomy is another challenge altogether. Case reports and small clinical studies are still appreciated.

Dr Patel: Mannequin studies are of limited value but they still do have a role in teaching, training, and familiarization with equipment in a way that may not be possible in human studies. There is a further ethical question in that if we believe only human studies on known difficult airway patients are of value in assessing new devices, how do we gain the experience to use these new difficult airway devices?

Dr Wong: Yes, I agree. The validity of transferring learning models to real-life patient situations is not established.

3. What airway device is underused or undervalued?

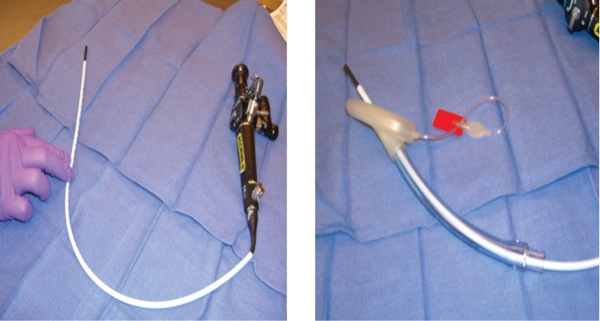

Dr Berkow: If I had to pick one device that I think is underused or undervalued, I would choose the Aintree Intubation Catheter (AIC; Cook Medical). In combination with a flexible fiberscope, it is a great device for intubation via an SGA device. It is especially useful in the CICO scenario where the SGA has saved the day and restored ventilation and oxygenation, but waking up the patient is not an option. In this scenario, where an ETT is needed but the thought of removing the SGA is scary, this technique is a great choice, as it allows ventilation and oxygenation during placement of the Aintree catheter with fiberscope combination.

The AIC is a hollow catheter that allows gas exchange via an adaptor and also will accommodate a 4.5-mm or smaller flexible fiberscope (Figure 2). It is important to note that larger-bore flexible scopes will not fit inside this catheter. The AIC with flexible scope combination can fit inside an SGA, and the catheter is long enough to allow removal of the SGA while the catheter remains in the trachea. After the SGA is removed, an ETT 6.5 mm or larger can be passed over the catheter into the trachea. If a swivel adaptor is used, ventilation can be continued through the majority of the procedure. Several articles have described the value of this technique.17,18

Dr Doyle: In my view, the most underused or undervalued airway device is the airway introducer, also sometimes called an Eschmann stylet or somewhat incorrectly, a gum elastic bougie, or even just plain bougie.19 The device is potentially useful in 5 situations:

- whenever a good view of the glottis is not immediately available,20,21

- as an aid to the insertion of some SGAs,22,23

- to facilitate tracheal intubation when using an SGA as a conduit for intubation,17

- as an aid during tracheal tube change procedures,24 and

- as an aid to conducting an emergency cricothyroidotomy.25

Finally, always bear in mind that these devices can occasionally be responsible for airway injuries.26

Dr Jagannathan: The Intubating LMA (Fastrach, Teleflex) and the LightWand (Vital Signs). Both of these devices are useful in the bleeding airway, or any clinical situation where video laryngoscopes or fiber-optic bronchoscopes would be difficult to use because of copious secretions and/or bleeding. I feel that trainees are not being taught these techniques, particularly the use of blind intubation via the LMA Fastrach, which is associated with a relatively high success rate in adults. Light-guided techniques have also become relatively obsolete as companies are not manufacturing these devices anymore. The main issue is that lack of exposure during anesthesiology residency leads to lack of use of these devices when these residents become attendings, leading to a ‘training gap’ for these valuable devices.

Additionally, I have observed the same pattern of disuse with flexible fiber-optic intubation. Given the effectiveness and availability of video laryngoscopes in recent years, the use of fiber-optic bronchoscopes has gone down dramatically. Given that the skill set of being comfortable with use of the LMA Fastrach, LightWand, and fiber-optic bronchoscope is very steep when compared with use of video laryngoscopes, I predict we may have another training gap in a few years when it comes to performing flexible fiber-optic intubation. This device also soon may be underused because more and more young clinicians are more adept in the use of video laryngoscopes.

Dr Klock: I expect that many of my co-authors will nominate the gum elastic bougie for the most underused and undervalued device. Although I believe this is a very effective, low-cost, high-yield airway device, I will nominate the flexible intubation scope, also known as the fiber-optic bronchoscope, as most underused or undervalued. The NAP4 study1 collected data in 2008 and 2009. One of the major findings of the study was that there were numerous cases where awake fiber-optic intubation was indicated but not used. Suggested reasons for non-use included lack of skills, lack of confidence, poor judgment, and lack of equipment. Since that study was conducted, many hospitals (including my own) have seen increased use of video laryngoscopes and decreased use of flexible intubation scopes. I am a frequent user of video laryngoscope technology, and I acknowledge its convenience and utility. However, I also make a point of using a flexible intubation scope with my trainees and CRNAs. The flexible intubation scope can be used for the awake or anesthetized patient, with or without neuromuscular blockade, and it can gently steer around friable tumors, radiated tissue or distorted anatomy. The flexible intubation scope also can be used to facilitate intubation in those frustrating cases where VL lets the operator see the vocal cords but difficulty is encountered passing the tube into the trachea.

I encourage my colleagues to use the flexible intubation scope at least monthly in routine cases. This provides familiarity with equipment setup and maintenance of one’s skills. I worry that increased use of video laryngoscope technology and decreased use of the flexible intubation scope will cause the latter to become the next underused and undervalued airway technology.

Dr Patel: The gum elastic bougie. In the United Kingdom, it is probably the single most important tool that most anaesthetists use (along with video laryngoscopy) when dealing with difficult airway patients.

Dr Wong: My choice is the flexible bronchoscope. The lack of use and skill in performing a flexible bronchoscope–guided intubation is a direct result of our success with video laryngoscopy. Also with failure to intubate, the majority of cases can be rescued with an SGA, [and] awaken the patient to safety. In many parts of the world where I visit, seasoned clinicians and trainees are doing far less flexible bronchoscope intubations than 2 decades ago. Some don’t even do one a year.

But of course, waking up a patient is not always an option, and tracheal intubation is important to achieve. At that critical moment, the loss of the skill to do a flexible bronchoscope intubation can make the difference between life and death.

4. Under what conditions would a “tracheostomy under local anesthesia” be your recommended approach to airway management?

Dr Berkow: There are actually very few patients who require an awake tracheostomy, in my opinion. Most patients with a narrowed airway who require airway management can be intubated via an awake fiber-optic intubation. These patients may have glottic masses or subglottic stenosis, and usually present with mild to moderate stridor. In the absence of significant stridor, the airway is probably patent enough to accommodate a small-caliber ETT. If it is suspected that airway collapse may occur with sedation or induction of general anesthesia, an awake approach to the airway is probably the safest option.

However, some patients in whom the airway is so narrow that even a small-caliber ETT will not pass, should probably receive an awake tracheostomy under local anesthesia. These patients, especially if the airway narrowing is due to a glottic tumor, will ultimately need a tracheostomy anyway for their airway to remain patent.

Awake tracheostomy allows the patient to maintain spontaneous respiration as well as airway patency, and provides the surgeon with time to safely perform the tracheostomy. Some patients, however, may have significant anxiety and/or agitation due to hypoxia, and may be challenging to manage awake with just local anesthesia. Careful, judicious sedation may be used in these patients, with the goal to relieve anxiety while maintaining adequate respiration.

A recent study, published in 2015 by Fang et al,27 found that 85% of patients who underwent awake tracheostomy presented with acute upper airway obstruction due to malignancy, and most had advanced disease. Over half of those patients presented with hoarseness or stridor.

Dr Doyle: Figure 3 provides a nice example from the literature.28 Typically, the suggestion of a tracheostomy under local anesthesia comes from the surgeon and often involves a stridorous patient with a nasty laryngeal tumor that would make conventional airway management inappropriate. I distinctly remember one such case where we gave Heliox (70% helium, 30% oxygen) to the patient by face mask during the initial part of the tracheostomy procedure, with the stridor soon vanishing as a result of the significantly reduced gas turbulence. The reduced work of breathing also greatly helped put the patient at ease.

Dr Jagannathan: A “tracheostomy under local anesthesia” would be my recommended approach to airway management in patients with complex head and neck masses (tumors) where the supra- and/or subglottic larynx is distorted and occupied by tumor. Moreover, trans-oral/nasotracheal intubation may be impossible, associated with bleeding, coring, and/or airway obstruction by the tumor. Given that many of these patients can have impending airway obstruction, administration of sedative agents can result in worsening airway obstruction, and this approach can have benefits. For all of the above reasons, a tracheostomy under local anesthesia may be the most suitable option for airway management in these patients. With newer approaches for complex head and neck patients, such as the use of THRIVE (transnasal humidified rapid-insufflation ventilatory exchange), the frequency of “awake tracheostomy” may be reduced.

Dr Klock: Awake FONA through either the trachea or cricothyroid membrane is not used frequently in my hospital. Scenarios where this might be employed as the primary approach include, but are not limited to:

- inability to open the patient’s mouth and contraindication to nasal intubation,

- severe facial trauma that makes it likely that mask ventilation and/or intubation will be difficult or impossible, and

- known friable supraglottic tumor causing critical airway obstruction.

Dr Osborn: I have been asked to assist in this type of case, usually when the patient has significant airway distress from a laryngeal tumor or tracheal stenosis. It usually goes well when certain precautions are taken and the patient can be kept calm throughout the process.

Dr Patel: This is the question to which all trainees want to know the perfect answer; I don’t believe there is one. The decision to undertake a tracheostomy under local anesthesia depends on, in my opinion, 5 factors:

- the experience of the anesthesiologist,

- the experience of the surgeon,

- the condition of the patient,

- the immediacy of airway intervention, and

- the hospital environment and assistance.

Consider a patient who presents with stridor to a tertiary care center with experience in managing complex airways and stridor. It may be entirely appropriate to induce anesthesia and attempt intubation, but recognize this may fail, and have the team available to perform rigid bronchoscopy or jet ventilation or insert a TTJV catheter or an immediate surgical airway. The same patient presenting to an isolated small hospital without the equipment or experience in advanced airway management may be managed completely differently and entirely appropriately for that environment—ie, tracheostomy under local anesthesia.

My own thresholds for a tracheostomy under local anesthesia are the combination of a high probability of failure to ventilate and intubate in combination with grossly distorted neck anatomy, making any kind of emergency surgical airway rescue impossible.

Dr Wong: This is a rare occurrence. To do a trach under local, the risk involved in attempting an awake intubation must be deemed excessively high. The most common situation I can think of is a critically narrowed upper airway in a stridorous patient. The etiology of upper airway obstruction may be tumor, abscess, or hematoma. In the case of an impending upper airway obstruction, one can plan to do an awake intubation with a double setup—the neck is prepped and a team is ready to do a surgical airway. However, while attempting topicalization and fiber-optic bronchoscope insertion into the pharynx/glottis, complete airway obstruction may ensue, resulting in rapid hypoxemia and arrest. A slash surgical airway rescue may not be immediately successful. If the surgical team or anesthesiologist is quite concerned with this scenario, then an awake trach may be a safe and more comfortable option.

5. Should anesthesiologists attempt mask ventilation prior to administering neuromuscular blocking drugs during the induction of general anesthesia?

Dr Berkow: Many provocative editorials have debated this question in the literature.29,30 Several factors that occur during induction of anesthesia, such as delivery of sedatives and narcotics, contribute to airway collapse and increased airway reflexes and may be factors in causing difficult mask ventilation. The administration of neuromuscular blockade (NMB) can mitigate these increased airway reflexes and may also facilitate placement of an SGA for rescue ventilation. The argument that giving NMB removes the option of waking the patient up does not take into account the effects of these other medications on the ability to wake a patient up and restore a patent airway. And now, with the availability of sugammadex (Bridion, Merck), reversal of nondepolarizing muscle relaxants occurs much faster. It is important to note that reversal of NMB does not necessarily equate to adequate spontaneous ventilation and oxygenation in a patient who is difficult or impossible to ventilate, especially in the setting of other sedating medications.

It is rare to encounter both difficult mask ventilation and difficult intubation in the same patient. In the patient with difficult mask ventilation, intubation will be easier if muscle relaxation has already been given.

Two recent studies in patients predicted to have difficult mask ventilation measured tidal volumes both before and after the administration of muscle relaxation and found significantly higher tidal volumes after delivery of NMB.31,32 These recent studies support the argument that NMB facilitates mask ventilation, and that confirming mask ventilation prior to NMB administration is not required.

Dr Doyle: When I was a resident some 3 decades ago, the conventional wisdom was that one should always attempt mask ventilation after anesthesia was induced before any neuromuscular blocking drug (NMBD) is administered. The only exception was for patients undergoing a rapid sequence induction (RSI). The rationale at the time was that should mask ventilation be impossible, the patient could be more easily returned to their awake native state and a new plan (eg, awake intubation) launched.

Since that time, the world’s collective experience has forced a reappraisal of that dogma. Early critics of the dogma pointed out that in such circumstances, severe hypoxemia is more likely to be avoidable by intervening pharmacologically rather than simply relying on repeated attempts to optimize mask ventilation. In particular, when mask ventilation becomes near impossible because of laryngospasm (certainly among the most common reasons that post-induction mask ventilation may be impossible), the situation can often be improved either by deepening the anesthetic (eg, giving more propofol) or—even more reliably—by administering a muscle relaxant.

The value of muscle relaxants in improving mask ventilation is supported by solid scientific evidence. For example, in a study by Joffe et al31 involving 210 patients, the authors measured tidal volumes during mask ventilation under initial and post-relaxant conditions and noted that face mask ventilation (FMV) was better when patients were given a muscle relaxant.

Given these considerations, as well as the launching of sugammadex (finally!), a reappraisal has taken place among the thought leaders in our profession. For example, Calder and Yentis wrote:

“Practitioners who believe that the administration of a NMB might help when difficulty with the airway is encountered should be able to exercise their judgement without fear of criticism. If anaesthetists hesitate to give NMB agents when necessary, this will be a retrograde step in patient safety.”30

Similarly, in a review article by Priebe, the author wrote:

“Thus, the earliest administration of a muscle relaxant following induction of anesthesia may well be the most effective and safest practice. Insistence on demonstration of adequate FMV before administration of a muscle relaxant is more of a ritual than an evidence-based practice. It should therefore be abandoned.”33

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Dr Jagannathan: No, anesthesiologists should not attempt mask ventilation prior to administering NMBDs during the induction of general anesthesia. Facemask ventilation is more effective following NMBDs, as shown by a number of studies. Use of NMBDs effectively reduces pharyngeal/laryngeal tone, often improving mask ventilation, conditions for SGA placement, and intubating conditions. The first step in difficult airway management is the decision to induce anesthesia versus perform an awake technique. When we decide to administer anesthetic agents, we have already deemed that the patient is easy to mask ventilate. Risk factors associated with difficult/impossible mask ventilation are known and predictable (difficult mask risk factors: body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, presence of a beard, Mallampati class III/IV, age ≥57 years, history of snoring; impossible mask risk factors: presence of a beard, neck radiation, male sex, sleep apnea, Mallampati class III/IV). In patients with many of the above risk factors, it may be prudent to perform an awake technique. The practice of test ventilation after administration of an induction agent is a defensive practice, commonly observed in the United States because of its litigious culture, and I personally do not advocate this practice.

Dr Klock: When I was a resident during the early 1990s, the standard of care was to establish that one could mask ventilate the patient prior to delivering a nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocker (NMB). The thinking was, “If we can’t mask ventilate, we can either administer succinylcholine and attempt direct laryngoscopy and intubation, or we can awaken the patient and attempt to intubate the patient while awake or under sedation.” This is an example of medical sophistry: A reasonable-sounding argument is proposed but it is actually false.

We know from Kheterpal’s 2013 study of combined difficult mask ventilation and difficult intubation that of the 698 cases of difficult mask ventilation, there were 19 cases with a specific comment that mask ventilation improved after administration of an NMBD.34 That study of nearly a half-million anesthetics found no reports of mask ventilation becoming more difficult after administration of an NMBD. We also know that omitting an NMB increases the relative risk for difficult tracheal intubation by a factor of up to 13 (95% CI, 8-21).35

My current practice for most cases is to administer the anesthetic induction agent followed immediately by the NMBD. I encourage ventilation via face mask using peak pressures equal to or less than 15 cm H2O. I will often use pressure-controlled ventilation from the anesthesia machine set to a pressure of 15 cm H2O, and I frequently notice that the tidal volumes delivered improve significantly as the NMBD takes effect. I won’t criticize my colleagues who continue to check for adequate mask ventilation prior to giving an NMBD, but I think a reasonable response to difficult mask ventilation would be administration of an NMBD.

Dr Osborn: I must admit that in my training (years ago), this principle was taught and many of my colleagues adhere to it today. Honestly, unless I am profoundly concerned about my ability to mask ventilate, I no longer attempt this maneuver before giving relaxants. I don’t believe it’s because I am impatient, but as I perform inductions and observe trainees, it appears that mask ventilation is generally improved by the administration of muscle relaxants; so therefore, what’s the point of checking? If you can’t ventilate, you will likely proceed to intubation and you will need adequate conditions for doing this, so why not just give the relaxant?

Dr Patel: This was so eloquently phrased in an editorial in 2008, by Ian Calder and Steve Yentis, as the choice between “Squirt-Puff-Squirt” or “Squirt-Squirt-Puff.”30 Their conclusion, and my own practice on patients that are not expected to be difficult, is “Squirt-Squirt-Puff.” This, I feel, is logical since the evidence suggests that with NMBDs ventilation either remains unchanged or improves, but does not deteriorate in cases of normal and difficult face mask ventilation; provides optimal conditions for face mask ventilation; and if impossible face mask ventilation develops, airway rescue is facilitated. No airway technique under general anesthesia is guaranteed to work always, but NMBDs are much more often the answer than the problem.

Dr Wong: No. For patients with a high suspicion of difficult airway (intubation/mask vent/surgical) and high risk for oxygen desaturation, an awake intubation should be done. In patients for whom the suspicion of difficult airway is moderate/low, I suggest a normal induction with rocuronium. The logic is, if you give propofol and the patient is easy to mask ventilate, give rocuronium. If the patient is not easy to ventilate, I would still give rocuronium. I have not seen anyone abandon induction and wake the patient up in that situation. Also, I will be prepared with backup airway equipment with plans B and C and sugammadex at all times because unanticipated difficult intubation can occur anytime and our prediction for difficult intubation is not very good.

6. Under what conditions, if any, do you employ deep extubation?

Dr Berkow: My answer really depends on the definition of “deep extubation.” As a neuroanesthesiologist, in the majority of the cases in which I provide care, a neurologic exam prior to extubation is desired by the surgeons. In addition, hypoventilation after extubation can result in elevated carbon dioxide levels, which can be undesirable after craniotomy. On the other hand, coughing and bucking during extubation is also not desirable after these procedures, as it can increase intracranial pressure. So while I do not routinely employ true deep extubation where the patient is deeply asleep and still unresponsive, I do often employ a “just barely awake” extubation for some of my neurosurgical as well as sinus surgery procedures, where the patient is awake enough to provide a neurologic exam and is breathing spontaneously but still is not fully awake. I find that the use of a remifentanil infusion for these procedures often can facilitate these extubation conditions. I will often also spray the vocal cords with lidocaine at the time of intubation to further reduce coughing during removal of the tube, although if the surgical procedure is of long duration, sometimes this effect has worn off by extubation.

I do believe that it is important to choose patients for deep extubation carefully, and weigh the pros and cons of extubating a patient not yet completely awake. Obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea can be particularly challenging to extubate deep, and I generally avoid this technique in this patient population unless the risks for coughing during extubation are extremely high.

Dr Doyle: Deep extubation (ie, ETT removal before the return of airway reflexes) is sometimes advocated by anesthesiologists who are seeking to avoid a stormy wakeup complicated by laryngospasm, bucking, or coughing—events that can lead to hematoma formation and even wound dehiscence. Still, practitioners of deep extubation are quick to remind us that there are some patients where the technique is ill-advised: difficult airway patients, patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea, morbidly obese patients, and patients at risk for aspiration. In addition, we are reminded that the patient should have a quasi-normal spontaneous respiratory pattern before deep extubation is attempted. Finally, insertion of an airway adjunct, such as a nasopharyngeal airway prior to extubation (whether deep or awake) may sometimes be advisable.

The above notwithstanding, I personally rarely perform deep extubations, preferring to extubate such cases in a mostly awake state by either employing a low-level remifentanil infusion or making the airway less reactive by administering endotracheal lidocaine with the ETT cuff temporarily deflated. An IV lidocaine bolus of 1.5 mg/kg at the end of anesthesia is also known to reduce coughing and other undesirable extubation events.

Dr Jagannathan: I regularly perform deep extubation in my patients. I work at a children’s hospital, and the majority of cases are patients with a high risk for reflex activation of the airway (eg, asthma, upper respiratory tract infections, adenotonsillectomy). I often also work in high turnover rooms (not uncommon to do 8-10 cases in 1 operating room). This combination makes deep extubation a suitable technique to minimize airway reflexes and facilitate operating room turnover. Additionally, I perform deep extubations on patients after neurosurgical and/or open eye surgeries where coughing/bearing down may be unsuitable during emergence from anesthesia. It is important to emphasize that when performing deep extubations you have adequately skilled personnel in the PACU, as use of CPAP/mask ventilation may be needed to mitigate the risk for laryngospasm during emergence from anesthesia.

Dr Klock: I want my trainees to be familiar with deep extubation, so we practice this in a number of circumstances. I also use the Bailey maneuver, which is the insertion of an SGA, such as the LMA ProSeal (Teleflex), prior to extubating the patient’s trachea. This allows the patient to awaken with an SGA in place, gaining many of the advantages of deep extubation while minimizing the risk for airway obstruction and the need for a tight face mask seal. In my practice, some of the common indications for deep extubation include:

- severe asthma or increased risk for bronchospasm during emergence,

- wanting to reduce the risk for a “stormy emergence,”

- wanting to minimize increases in blood pressure and venous pressure in the head and neck following neurosurgery and some head and neck procedures, and

- teaching purposes.

Dr Osborn: As a neuroanesthesiologist, I am expected to perform a well-timed and smooth extubation that prevents excessive coughing, bucking, etc. There have been cases where it was important and recommended. I feel quite confident in my timing and decision making because extubation is indeed an art in anesthesia and medicine. If the surgeon requests a deep extubation for plastic surgery, abdominoplasty, ear surgery, etc, I am happy to comply.

Dr Patel: Deep extubation is an advanced technique, in which experience is essential and vigilance is required until the patient is fully awake. I employ deep extubation in patients who are breathing spontaneously with uncomplicated airways. The 2012 Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of tracheal extubation36 described the technique:

- Ensure that there is no further surgical stimulation.

- Balance adequate analgesia against inhibition of respiratory drive.

- Deliver 100% oxygen through the breathing system.

- Ensure adequate depth of anesthesia with a volatile agent or total IV anesthesia (TIVA), as appropriate.

- Position the patient appropriately.

- Remove oropharyngeal secretions using a suction device, ideally under direct vision.

- Deflate the tracheal tube cuff. Airway responses such as coughing, gagging, or a change in breathing pattern indicate an inadequate depth and the need to deepen anesthesia.

- Apply positive pressure via the breathing circuit and remove the tracheal tube.

- Reconfirm airway patency and adequacy of breathing.

- Maintain airway patency with simple airway maneuvers or an oro/nasopharyngeal airway until the patient is fully awake.

- Continue delivering oxygen by mask until recovery is complete.

- Anesthetic supervision is needed until the patient is awake and maintaining his or her own airway.

Dr Wong: I am in an adult practice and rarely ever extubate deep. The major advantage is a smooth awakening, but it may be risky with aspiration, laryngospasm, and airway obstruction. If it’s the coughing and autonomic responses that I wish to reduce, in such cases as carotid endarterectomy or thyroidectomy, I would keep the patient asleep until surgery is done, suction the pharynx, extubate, insert the SGA, and let him or her wake up smoothly with an SGA.

7. Even though a number of tests and scoring systems are available to help predict a difficult airway, many clinicians regard them as being close to useless as long as the patient can reasonably open his or her mouth and video laryngoscopy is available. What is your take on this matter?

Dr Berkow: Although studies have yet to develop a single test or constellation of tests that have high sensitivity or specificity, my opinion is that performing an airway assessment and gathering an airway history is still of value. Safe airway management is all about trying to predict difficulty and being adequately prepared in case difficulty arises.

I believe looking at a constellation of tests and symptoms together can still be useful, especially if the choice is between an awake and an asleep intubation. I might consider an awake intubation in a morbidly obese patient with an elevated Mallampati score, thick neck, full beard (which sometimes hides a micrognathic jaw), and severe obstructive apnea, compared with the same morbidly obese patient with a Mallampati I score and no obstructive sleep apnea history or beard. These tests can potentially help create backup plans, such as availability of SGAs if mask ventilation may be difficult, or a video laryngoscope if an anterior glottis is suspected.

When I approach any patient requiring airway management, I ask several important questions, and use the data from an airway history and airway exam to plan my approach:

- Will the patient be difficult to mask ventilate?

- Will the patient be difficult to intubate?

- Will SGA placement be challenging?

- What are my backup plans and resources?

- Are these plans and resources readily available?

The bottom line is, there is minimal risk in collecting advanced airway equipment “just in case” but not needing to use it. I would prefer to be in that situation compared with needing equipment urgently or emergently and not having it immediately available.

In the words of Richard Levitan, related to airway management, “We should practice it with obsessive attention to detail and with redundant safeguards. Despite the effectiveness of video laryngoscopy, we must always have more than 1 way to safely manage the airway.”37

Dr Doyle: It has been suggested that predicting difficult tracheal intubation is useless because of the poor predictive capacity of individual signs and scores. Despite the worldwide availability of airway scoring systems, in a large Danish study of 3,391 difficult intubations, 3,154 (93%) were unanticipated, while difficult mask ventilation was unanticipated in 808 of 857 (94%) cases.38Such an experience and the experience of countless others suggest that every anesthesia provider should have training in management of the difficult airway (including cricothyroidotomy training) and should be provided with immediate access to both routine airway equipment (eg, video laryngoscopes, airway introducers/bougies) and special airway equipment (eg, fiberscopes, cricothyroidotomy kits). Note, however, that just because the patient can open his or her mouth well is no guarantee that the airway will be easy to manage, even with video laryngoscopy; every experienced anesthesiologist can tell a “war story” to support this maxim.

Dr Jagannathan: Although there are a variety of preoperative tests and scoring systems performed in helping to predict a difficult airway, they are not reliable. I do generally agree that if a patient has a reasonable mouth opening (perhaps the most important preoperative test), then a video laryngoscope or SGA can be likely placed, and the trachea can likely be intubated (barring a large head and neck tumor). The most important decision in airway management is whether to perform airway management awake versus asleep, then to decide which device may be most suitable. Both of these decisions typically depend on the patient’s overall appearance, physiology, and comorbidities. Clinical experience and a general gestalt are needed, and more important are preoperative tests to determine if the airway may be problematic to manage. Perhaps in the future, with the use of ultrasound in combination with preoperative tests, there can be greater reliability in predicting the difficult airway.

Dr Klock: I find this proposition deeply concerning. I fear that many anesthesia providers have a false sense of security due to the utility of video laryngoscopy. There are many causes of impossible intubation and difficult face mask ventilation other than poor mouth opening. Risk factors include radiation changes, Mallampati class III or IV, male sex, limited thyromental distance, body mass index greater than 30, and presence of teeth.34

Some of the key findings from the NAP4 study1 were that poor airway assessment was a contributing factor to many of the adverse outcomes. A proper assessment may indicate that an awake or flexible intubation scope technique should be used. The authors of the study (as do I) recommend that airway management be approached with a strategy rather than a plan. A plan might be “induce anesthesia and intubate with video laryngoscopy.” A strategy is a coordinated, logical sequence of plans, which aim to achieve good gas exchange and prevention of aspiration. The ASA difficult airway algorithm39 or the Vortex approach40 can be used to develop an airway strategy that might include intubation with direct laryngoscopy, video laryngoscopy, or the flexible intubation scope and ventilation with a face mask or an SGA. Since none of our assessment tools has 100% sensitivity, equipment and providers should be immediately available to provide emergency FONA in case a CICO scenario is encountered. Video laryngoscopes are an important part of the airway manager’s armamentarium but they cannot be relied upon to secure every patient’s airway.

Dr Osborn: I still believe that assessment should be done carefully and that degree of mouth opening in addition to neck mobility is important. The presence of teeth and their ability to distort the blade placement is another factor. I don’t believe that video laryngoscopes are the answer to every difficult intubation.

Dr Patel: While it may be true that despite decades of research on predicting the difficult airway we still have relatively poor tests in terms of sensitivity and specificity, I still gain a lot of information and feel better prepared for airway management having assessed Mallampati, looked at the mouth and teeth, observed the neck for a short thyromental distance and ease of placement of a surgical airway, and checked for neck movements. This information allows me to choose the best tools for airway management with minimal trauma to laryngopharyngeal tissue.

Dr Wong: There is some truth in this thinking. However, we should be assessing potential difficulties in all aspects of airway management—mask ventilation, intubation, SGA, surgical airway, and propensity for hypoxemia. Mouth opening is not the only predictor! For example, a patient with an anterior larynx or neck radiation may have a good mouth opening but a very difficult airway. In a study by Nørskov et al,38 among a Danish database of over 188,000 cases, 3,391 difficult intubations were identified, of which 3,154 (93%) were unanticipated. Therefore, even in routine general endotracheal anesthesia cases, one should be fully prepared for unanticipated difficult intubation; plans B and C, sugammadex, and appropriate airway equipment should all be readily available.

References

- Cook TM, Woodall N, Frerk C. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 1: anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106(5):617-631.

- Timmermann A, Chrimes N, Hagberg CA. Need to consider human factors when determining first-line technique for emergency front-of-neck access. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(1):5-7.

- Booth AWG, Vidani K. Human factors can’t intubate can’t oxygenate (CICO) bundle is more important than needle versus scalpel debate. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):466-468.

- Duggan LV, Ballantyne Scott B, et al. Transtracheal jet ventilation in the ‘can’t intubate can’t oxygenate’ emergency: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(suppl 1):i28-i38.

- Frerk C, Mitchell VS, McNarry AF, et al. Difficult Airway Society intubation guidelines working group. Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115(6):827-848.

- Wong DT, Mehta A, Tam AD, et al. A survey of Canadian anesthesiologists’ preferences in difficult intubation and “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” situations. Can J Anesth. 2014;61(8):717-726.

- Schebesta K, Hupfl M, Rossler B, et al. Airway anatomy of high-fidelity simulators and airway trainers. Anesthesiology.2012;116(6):1204-1209.

- Misiak M, Osadzinska J, Jarosz J, et al. Simulation vs clinical practice—airway management with the laryngeal tube. Eur J Anaesth. 2004;21:A285:71.

- Howes BW, Wharton NM, Gibbison B, et al. LMA Supreme insertion by novices in manikins and patients. Anaesthesia. 2010;65(4):343-347.

- Rai MR, Popat MT. Evaluation of airway equipment: man or manikin? Anaesthesia. 2011;66(1):1-3.

- Patil V, Barker GL, Harwood RJ, et al. Training course in local anaesthesia of the airway and fibreoptic intubation using course delegates as subjects. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89(4):586-593.

- Woodall NM, Harwood RJ, Barker GL. Complications of awake fiberoptic intubation without sedation in 200 healthy anaesthetists attending a training course. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(6):850-855.

- Silsby J, Jordan G, Bayley G, et al. Evaluation of four airway training manikins as simulators for inserting the LMA Classic. Anaesthesia. 2006;61(6):576-579.

- Jackson KM, Cook TM. Evaluation of four airway training manikins as patient simulators for the insertion of eight types of supraglottic airway devices. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(4):388-393.

- Appelboam R, Snow D. A simple and cheap training tool for airway endoscopy. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(6):641-642.

- Schebesta K, Huepfl M, Roessler B, et al. Degrees of reality: Airway anatomy of high-fidelity human patient simulators and airway trainers. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(6):1204-1209.

- Wong DT, Yang JJ, Mak HY, et al. Use of intubation introducers through a supraglottic airway to facilitate tracheal intubation: a brief review. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59(7):704-715.

- Berkow L, Schwartz L, Kan K, et al. Use of the laryngeal mask airway-Aintree Intubating Catheter-fiberoptic bronchoscope technique for difficult intubation. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23(7):534-539.

- Grape S, Schoettker P. The role of tracheal tube introducers and stylets in current airway management. J Clin Monit Comput. 2017;31(3):531-537.

- Law JA, Broemling N, Cooper RM, et al. The difficult airway with recommendations for management—part 1—difficult tracheal intubation encountered in an unconscious/induced patient. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60(11):1089-1118.

- Rai MR. The humble bougie…forty years and still counting? Anaesthesia. 2014;69(3):199-203.

- Brimacombe J, Keller C, Judd DV. Gum elastic bougie-guided insertion of the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway is superior to the digital and introducer tool techniques. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(1):25-29.

- Teoh CY, Lim FS. The Proseal laryngeal mask airway in children: a comparison between two insertion techniques. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18(2):119-124.

- Umesh G, Sushma KS, Sindhupriya M, et al. Gum elastic bougie as a tube exchanger: modified technique. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59(12):827-829.

- Heard AM, Green RJ, Eakins P. The formulation and introduction of a ‘can’t intubate, can’t ventilate’ algorithm into clinical practice. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(6):601-608.

- Sahin M, Anglade D, Buchberger M, et al. Case reports: iatrogenic bronchial rupture following the use of endotracheal tube introducers. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59(10):963-937.

- Fang CH, Friedman R, White PE, et al. Emergent awake tracheostomy—the five-year experience at an urban tertiary care center. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(11):2476-2479.

- Arab AA, Almarakbi WA, Faden MS, et al. Anesthesia for tracheostomy for huge maxillofacial tumor. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8(1):124-127.

- Ramachandran SK, Kheterpal S. Difficult mask ventilation: does it matter? Anaesthesia. 2011;66 (suppl 2):40-44.

- Calder I, Yentis SM. Could ‘safe practice’ be compromising safe practice? Should anesthetists have to demonstrate that face mask ventilation is possible before giving a neuromuscular blocker? Anaesthesia. 2008;63(2):113-115.

- Joffe AM, Ramaiah R, Donahue E, et al. Ventilation by mask before and after the administration of neuromuscular blockade: a pragmatic non-inferiority trial. BMC Anesthesiology. 2015;15:134.

- Soltesz S, Alm P, Mathes A, et al. The effect of neuromuscular blockade on the efficiency of facemask ventilation in patients difficult to facemask ventilate: a prospective trial. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(12):1484-1490.

- Priebe HJ. Should anesthesiologists have to confirm effective facemask ventilation before administering the muscle relaxant? J Anesth. 2016;30(1):132-137.

- Kheterpal S, Healy D, Aziz MF, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of difficult mask ventilation combined with difficult laryngoscopy: a report from the multicenter perioperative outcomes group. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(6):1360-1369.

- Lundstrøm LH, Duez CH, Nørskov AK, et al. Avoidance versus use of neuromuscular blocking agents for improving conditions during tracheal intubation or direct laryngoscopy in adults and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;5:CD009237.

- Popat M, Mitchell V, Dravid R, et al. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of tracheal extubation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(3):318-340.

- Levitan R. Videolaryngoscopy, regardless of blade shape, still requires a backup plan. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(4):421-422.

- Nørskov AK, Rosenstock CV, Wetterslev J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of anaesthesiologists’ prediction of difficult airway management in daily clinical practice: a cohort study of 188 064 patients registered in the Danish Anaesthesia Database. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(3):272-281.

- Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology.2013;118(2):251-270.

- Chrimes N. The Vortex: a universal “high-acuity implementation tool” for emergency airway management. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117 (suppl 1):i20-i27.