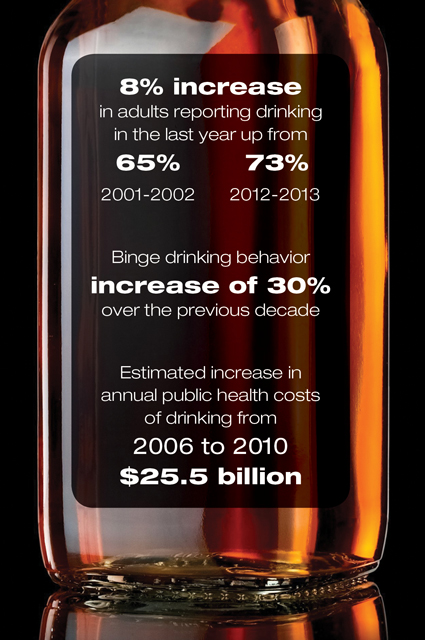

In the United States, more people are consuming alcohol, with the share of adults who reported drinking in the last year up from 65% in 2001-2002 to 73% in 2012-2013. The data also illustrate rising percentages of high-risk or binge drinking behavior, defined as more than four standard drinks for women, or more than five for men, on any day at least weekly. Roughly 13% of Americans met these criteria in the period 2012-2013, an increase of 30% over the previous decade. Rates of high-risk drinking rose faster in women, people over the age of 65 years, minorities and individuals of a lower socioeconomic status.1

The increasing use of alcohol correlates with other studies evaluating the public health costs of alcohol consumption. In 2010, the total annual costs of drinking were estimated at $249 billion, an increase from $223.5 billion in 2006.2 The majority of the costs were linked to binge drinking.

Deaths related to alcohol use also are on the rise. The CDC estimates that about 88,000 people per year die as a result of direct (alcoholic liver disease [ALD]) and indirect factors (cancers, motor vehicle crashes, falls, homicides, suicides) associated with drinking.3 The most recent estimates reported 34,865 deaths in 2016 from alcohol-induced causes.4 The age-adjusted death rate was 9.5 per 100,000 people in this country, an increase of 26% from 2000.

While the age-adjusted death rate was more than two times higher in men than women, the annual increases in mortality are rising faster in women, which corresponds with rising rates of binge drinking among women. In addition, a recent analysis of CDC data showed that mortality rates from cirrhosis are rising, particularly among people aged 25 to 34 years, which is driven by sepsis or peritonitis related to alcoholic cirrhosis.5 The number of deaths more than doubled in young Native Americans, Asian/Pacific Islanders and whites.

To stem the rise in ALD-related mortality, a concerted effort across multiple levels within the health care system is imperative. Policymakers should tighten the control of alcoholic beverages and taxation policies, and increase funding for mental health and substance abuse programs. Primary care providers should screen all patients for alcohol use disorder and offer early referrals to substance abuse counseling, addiction medicine or hepatology specialists, if evidence of liver disease is present. Ultimately, novel treatments for both alcohol abuse and ALD are urgently needed.

Discussing Alcohol Use

Given these grim statistics for a preventable problem, what can be done to counter this public health epidemic at the clinical level? All providers should become comfortable in discussing alcohol use with patients. That starts with knowing what constitutes a standard drink. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines a standard drink as 14 g of pure alcohol, which is equivalent to a 12-ounce can of beer with 5% alcohol, a 5-ounce glass of wine containing 12% alcohol, or a 1.5-ounce shot of liquor at 40% alcohol.6

The NIAAA recommends avoiding alcohol for individuals who are going to drive or operate machinery; take medications that interact with alcohol; have a medical condition, such as liver disease, that may be exacerbated by alcohol; or pregnant or trying to become pregnant.7

The exact safe amount of alcohol to consume is unknown, as no randomized clinical trial has been performed to determine a safe or beneficial amount of alcohol for the general population. A recent large, multicenter randomized NIAAA clinical trial to assess the health benefits of moderate drinking was canceled after investigative reporting revealed funding was solicited from the alcoholic beverage industry.8

A moderate amount of evidence suggests screening for alcohol use disorder in adults is beneficial and recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).11 The USPSTF advises using either the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) or Single Alcohol Screening Questionnaire as an initial screening tool; both include simple questions that can be administered in five minutes or less. If the screening tools are positive, the full AUDIT can be administered (Tables 1 and 2).12 A positive AUDIT score should lead to referral to an addiction medicine specialist for further treatment. The NIAAA has a helpful website to guide patients at https://alcoholtreatment.niaaa.nih.gov.

| Table 1. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C score): 4 or more for men and 3 or more for women is considered positive. | ||||||

| Questions | Scoring Table | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | Never | Monthly or less | 2-4 times a month | 2-3 times a week | 4 or more times a week | |

| How many standard drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day? | 1-2 | 3-4 | 5-6 | 7-9 | 10+ | |

| How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| Table 2. Modified Single Alcohol Screening Questionnaire (M SASQ) A score of 2 or higher is considered positive, and further evaluation is recommended. | ||||||

| Question | Scoring Table | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| How often have you had 6 or more standard drinks (if female) or 8 or more standard drinks (if male), on a single occasion in the last year? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG)13 and the European Association for the Study of the Liver14 published clinical practice guidelines on ALD in 2018. The ACG recommends that people who consume a heavy amount of alcohol (defined as more than three drinks per day for men and more than two per day for women) should be counseled that they are at increased risk for developing ALD and offered resources to help cut down on or quit drinking.

Patients with other chronic liver diseases, such as viral hepatitis or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, should minimize their intake or avoid alcohol entirely. Baclofen and brief motivational interviewing have low levels of evidence in preventing alcohol relapse.

In patients with a positive AUDIT score and abnormal liver enzymes, referral to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist—in addition to an alcohol addiction specialist—should be offered. Noninvasive testing with ultrasound or elastography can be used to assess for fibrosis; liver biopsy may be an option but is not routinely recommended in these patients.

In patients with alcoholic hepatitis (AH), management strategies consist of alcohol cessation, early enteral nutrition to increase caloric intake, treatment with corticosteroids (if no contradictions, moderate level of evidence), and consideration of referral to a liver transplantation center in highly selected patients. The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, Maddrey discriminant function (MDF) and Lille model are helpful in assessing severity of disease, and have moderate prognostic ability.

Patients with severe AH (MELD >20; MDF >32) should be hospitalized to assist with alcohol cessation, monitor for withdrawal, and rule out underlying infections. Although the FDA has not approved any drugs for AH, corticosteroids (40 mg daily of prednisone or prednisolone, or 32 mg per day of methylprednisolone) are often given off-label for 28 days followed by a gradual taper once infections have been ruled out. The Lille score (www.lillemodel.com/ score.asp) can be calculated on day 7; if the score remains high (>0.45), corticosteroids are often stopped, as risks of therapy outweigh benefits, and referral to a liver transplantation center in highly selected candidates is considered. An infusion of N-acetylcysteine can be given for five days while awaiting cultures or in conjunction with steroids due to a possible association with reduced risk for developing hepatorenal syndrome.15 A recent multicenter study involving early liver transplantation in AH demonstrated a one-year survival rate of 94% and a three-year survival rate of 84%. Sustained alcohol use after liver transplantation occurred in 10% and 17% of patients at one and three years, respectively, and was associated with higher mortality.16 Palliative care should be offered to patients with severe AH who continue to consume alcohol or are not deemed to be transplant candidates (see article, “Study Finds Strong Benefits Of Transplant in Alcoholic Patients”).

| Table 3. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

A score of 0-7 is considered low risk. A score of 8-15 is moderate risk, and brief interventions may be helpful such as feedback of AUDIT results, motivational interviewing, setting goals and limits, or self-monitoring of drinking. A score of 16 or more is indicative of high-risk drinking behavior and referral to addiction medicine or substance abuse counseling should be strongly considered.

|

||||||

| Questions | Scoring Table | Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | Never | Monthly or less | 2-4 times a month | 2-3 times a week | 4 or more times a week | |

| How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking? | 1-2 | 3-4 | 5-6 | 7-9 | 10+ | |

| How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected from you because of drinking? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking? | Never | Less than monthly | Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily | |

| Have you or someone else been injured as a result of your drinking? | No | Yes, but not in last year | Yes, during the last year | |||

| Has a relative or friend or a doctor or another health worker been concerned about your drinking or suggested you cut down? | No | Yes, but not in last year | Yes, during the last year | |||

References

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911-923.

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, et al. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(5):e73-e79.

- CDC. Alcohol-attributable deaths due to excessive alcohol use. https://nccd.cdc.gov/ DPH_ARDI/ Default/ Report.aspx?T=AAM&P=f6d7eda7-036e-4553-9968-9b17ffad620e&R=d7a9b303-48e9-4440-bf47-070a4827e1fd&M=8E1C5233-5640-4EE8-9247-1ECA7DA325B9&F=&D=. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(6):1-77.

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999-2016: observational study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2817.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. What is a standard drink? www.niaaa.nih.gov/ alcohol-health/ overview-alcohol-consumption/ what-standard-drink. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. www.niaaa.nih.gov/ alcohol-health/ overview-alcohol-consumption/ moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Dyer O. $100m alcohol study is cancelled amid pro-industry “bias.” BMJ. 2018;361:k2689.

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015-1035.

- Kypri K, McCambridge J. Alcohol must be recognised as a drug. BMJ. 2018;362:k3944.

- Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1899-1909.

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789-1795.

- Singal AK, Bataller R, Ahn J, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcoholic Liver Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(2):175-194.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of alcohol-related liver disease. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):154-181.

- Nguyen-Khac E, Thevenot T, Piquet M-A, et al. Glucocorticoids plus N-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1781-1789.

- Lee BP, Mehta N, Platt L, et al. Outcomes of early liver transplantation for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):422-430.e1.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.