Author: Michael Vlessides

Anesthesiology News

Pain management after cesarean delivery is improved with a concerted multidisciplinary effort that embraces multimodal management techniques, an Israeli study has found.

Study parturients reported significantly improved outcomes on several pain-related and adverse event measures, while the investigators observed a significant increase in the amount of nonopioid medications used.

“Our hospital’s acute pain service had not been running optimally in the past few years due to personnel changes and work overload,” said Ruth Edry, MD, the head of the acute pain service and a senior anesthesiologist at Rambam Medical Center, in Haifa, Israel. “Patients were not being optimally cared for. So when I became head of the service 18 months ago, I realized we could do a lot to change this, with significant potential benefit for our patients.”

Yet changing ingrained practices in a 1,000-bed university hospital is not an easy task. What’s more, Dr. Edry needed a starting point.

“So, I thought it would be important and beneficial to start with this surgery,” Dr. Edry said. “Our obstetrics staff responded enthusiastically and joined the research voluntarily.”

In the next step, Dr. Edry joined Pain Out, an international quality improvement and research network (pain-out.med.uni-jena.de). Using a patient-reported outcome tool developed and validated by the organization, Dr. Edry and her colleagues assessed pain outcomes among women undergoing cesarean delivery at her institution.

“We ran the questions for a month and had answers from 35 patients,” she said. “We saw that we were doing very, very poorly, both in absolute terms and compared to other centers in the Pain Out group.”

Simple Protocol, but Effective

Given these troubling findings, the researchers conducted a literature review to help identify the elements that would constitute their new pain management approach for these patients. The multimodal protocol they designed consisted of the following elements:

- intraoperative spinal anesthesia with morphine and fentanyl plus IV dexamethasone;

- wound infiltration at the end of surgery;

- intraoperative and ward administration of nonopioid analgesics around the clock for the first 24 hours and as needed thereafter;

- oral opioids as rescue medication; and

- discontinuation of metamizole (or dipyrone) to women intending to breastfeed.

“The protocol is not very complicated,” Dr. Edry said. What proved far more challenging was changing practices among clinicians at the institution. “I had to convince 250 staff members, nurses, surgeons and anesthesiologists to change their habits.”

In time, Dr. Edry’s peers saw the potential and benefits of the new program. “It took about three months, but after that things started to work according to the protocol,” she said.

As Dr. Edry explained, the two most difficult steps in the process were convincing ward nurses to administer around-the-clock medications for the first 24 hours and having surgeons perform wound infiltration at the end of the procedure.

“This was very difficult to change,” Dr. Edry said. “Once patients were pain-free, the nurses thought administering the next dose was unnecessary. But I engaged in a series of lectures to the nurses, many of whom had undergone C-sections at our institution. So I knew they would ultimately be sympathetic.”

Pain, Adverse Effects Outcomes Improve

To help determine the effectiveness of the new protocol, Dr. Edry studied changes in various patient-reported outcomes over time. The baseline evaluation was performed throughout August 2017, followed by assessments in each of the three quarters afterward. The statistical significance of changes was assessed by comparing values at baseline with the third quarter (Table).

| Table. Usage of Pain Medications at Baseline and by Quarter | ||||||

| Stage of Care | Medications | Baseline, % | Q1, % | Q2, % | Q3, % | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative | Nonopioids | 46 | 69 | 97 | 99 | <0.0001 |

| Wound infiltration | 0 | 11 | 74 | 76 | <0.0001 | |

| PACU | Nonopioids | 41 | 22 | 7 | 3 | <0.0001 |

| Opioids | 56 | 44 | 40 | 38 | 0.0751 | |

| Ward | Acetaminophen | 25 | 46 | 100 | 100 | 0.0267 |

| Ibuprofen | 39 | 49 | 93 | 95 | <0.0001 | |

| Metamizole | 89 | 65 | 9 | 7 | <0.0001 | |

| Opioids | 4 | 4 | 11 | 18 | 0.0173 | |

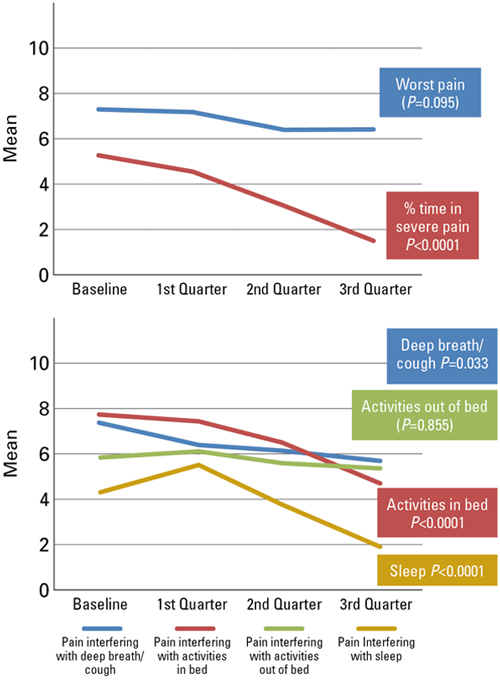

Among 552 patients approached between October 2017 and June 2018, 85% completed the questionnaire. The assessments revealed significant improvements in the percentage of time patients spent in severe pain (P<0.0001); pain interfering with breathing deeply (P<0.033); and pain with moving in bed (P<0.0001) (Figure 1).

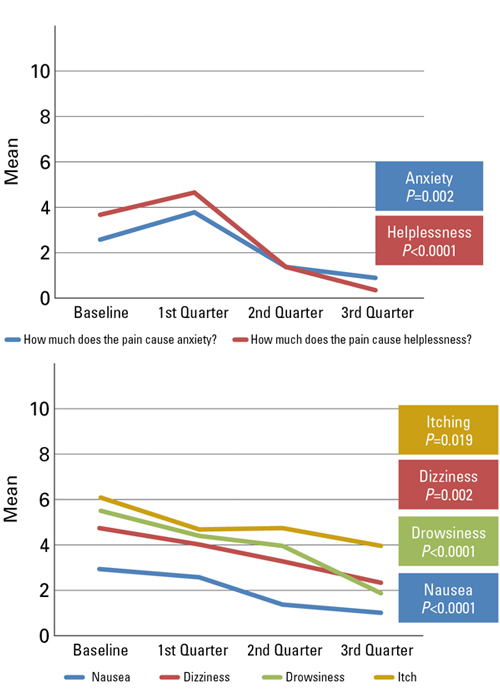

Furthermore, patients who received the new pain protocol documented significant improvements in nausea (P<0.0001) and feelings of helplessness (P<0.0001). There was also a decreased need for more pain treatment, but this was not significant (P=0.135) (Figure 2).

“Funnily enough, I had two staff members—a gynecologist and an obstetric nurse—who both had cesarean sections before and after the protocol,” she continued. “And they both came up to me afterward and said they had two very different experiences.”

For all the change’s challenges, Dr. Edry was confident that institutions facing pain management problems could implement similar protocols. “You have to speak with everyone, especially the nurses and surgeons,” she noted. “I feel like the staff got more engaged as they saw the results.

“You also need something to monitor your progress, or you won’t be able to illustrate your results,” she added. “Because if you can’t show your results, then I think staff becomes less engaged over time. That is why cooperation with the Pain Out registry is so important. It enables me to keep showing our staff members the data, and they are motivated to keep up our good work.”

Heather Nixon, MD, found that the research offered many encouraging results, including ones that have the potential to resonate long afte r the patient has been discharged. “One of the things they found is that not only did severe pain go down, but pain interfering with deep breathing and moving in the bed also decreased,” said Dr. Nixon, an associate professor of anesthesiology and the chief of obstetric anesthesiology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, in Chicago, who also is the vice chair of the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Obstetric Anesthesia.

“These are things that can really impact quality of life for women undergoing cesarean section. Patients who stay in bed, especially postpartum women, are more likely to get deep vein thrombosis and pneumonia, and are less likely to have interaction with their newborn baby, which can potentially interfere with bonding,” Dr. Nixon said.

The findings may have effects in the long term, too, Dr. Nixon said. “We know that between 10% and 30% of patients who undergo cesarean delivery will have chronic pain. The studies have borne that out over time,” she said. “These women often get hyperalgesic after surgery, and that might set them up for chronic pain. So if we control their pain better in the postpartum period by giving them scheduled doses of medicine, it might actually affect the outcome of long-term pain. That is an area that we really need to examine as these protocols become more commonplace.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.