Author: Michael Vlessides

Anesthesiology News

Has the time come for intraoperative methadone to be considered a legitimate postoperative analgesic? A study of the often beleaguered agent’s safety and efficacy indicates the answer may well be yes.

The meta-analysis—by Thomas Cheriyan, MD, and his colleagues at Augusta University, in Georgia—concluded that use of intraoperative methadone resulted in significantly lower pain scores than use of other opioids at both 24 and 72 hours after surgery, with no observed difference in the incidence of adverse events.

“A study published in Anesthesiology [2017;126(5):822-833] compared intraoperative methadone with hydromorphone, concluding that spine surgery patients receiving methadone had reduced postoperative opioid requirements, decreased pain scores and improved patient satisfaction with pain management,” said Dr. Cheriyan, a resident at Augusta. “It was quite an impressive study, and spurred us to look back and see if other studies had investigated this interesting research question.

“Once we examined the literature, we realized there’s been a fair amount of research in this area,” he said. “Nevertheless, many of these studies have been limited by small sample sizes, which prompted us to perform the meta-analysis.”

Standardized mean difference and pooled odds ratios were used for continuous and categorical data; a random effects model was used for analysis.

A total of eight studies comprising 419 patients were included in the meta-analysis. Among these, 207 patients received intraoperative morphine while 212 received methadone. The sample sizes of each varied between 30 and 115 patients.

Another Benefit: Less Post-op Morphine

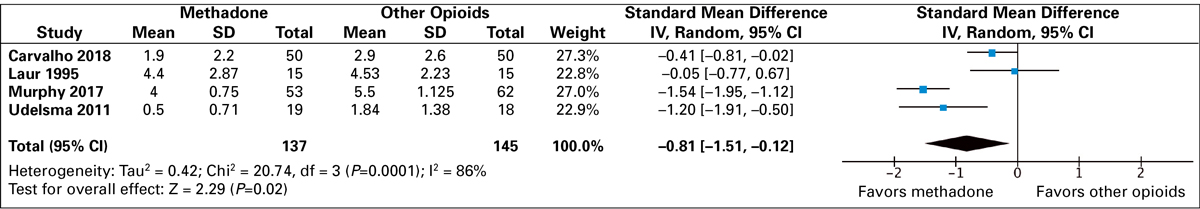

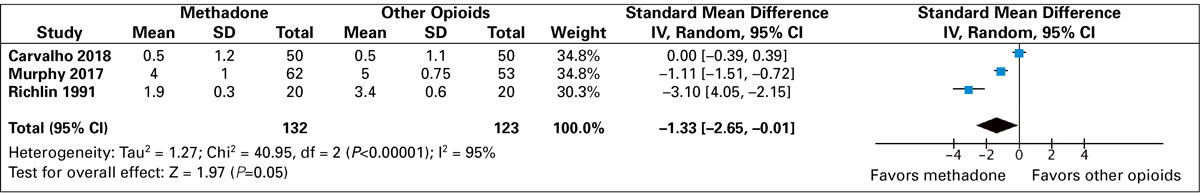

Presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (abstract A4298), Dr. Cheriyan explained that pain was found to be significantly lower among patients who received intraoperative methadone at both 24 hours (standard mean difference, –0.81; 95% CI, –1.51 to –0.12; P=0.02) and 72 hours (standard mean difference, –1.33; 95% CI, –2.65 to –0.01; P=0.05) after surgery (Figures 1 and 2).

“We did find significant heterogeneity in pain score reporting between the studies, so we could not quantify how much the pain score decreased by,” Dr. Cheriyan explained. “But at any rate, it was significantly lower at these time points with the methadone.”

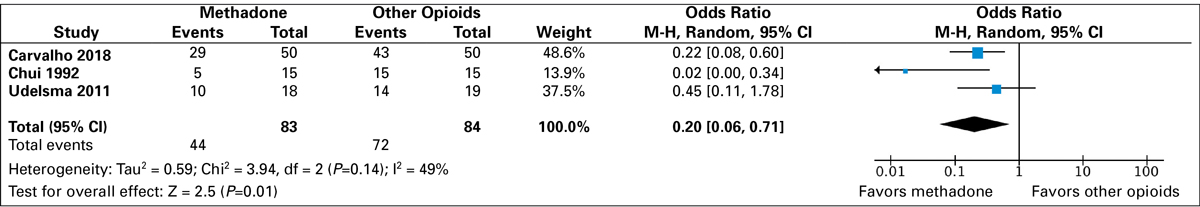

The analysis also found no difference between groups with respect to time to receiving first postoperative analgesic. However, among those studies that reported the outcome, only 53% of methadone patients received at least one dose of postoperative morphine, significantly fewer than the 85% (44/83 vs. 72/84; P=0.01) of those in the morphine group who required such a dose (Figure 3).

Perhaps not surprisingly, patients in the methadone group consumed significantly less morphine postoperatively than their counterparts given other opioids (standard mean difference, –3.18; 95% CI, –5.22 to –1.13; P=0.002).

No differences were found between groups with respect to time to extubation (standard mean difference, 0.14; 95% CI, –0.17 to 0.44; P=0.37). Also, there was no difference in the adverse event profile with respect to nausea and/or vomiting and respiratory depression.

Yes, but Questions Remain

Despite these promising results, Dr. Cheriyan recognized that there are many unanswered questions surrounding this type of methadone use. “There can be a high degree of variability in drug metabolism and relative analgesic potency among patients,” he said in an interview with Anesthesiology News. “The half-life can vary from eight to 60 hours.”

Although his institution does not use intraoperative methadone for postoperative pain, Dr. Cheriyan believes the meta-analysis might open the door to that possibility. “Most people don’t even consider intravenous methadone as a modality for postoperative analgesia,” he said. “And if it does provide superior postoperative pain management without an increase in adverse events, it could be a game changer. And considering the current opioid crisis, this actually might benefit in the long term as well.

“But until we have bigger studies, we will not really be able to tease out adverse events,” he added. “The adverse events are quite rare, and you need a very high sample size for it. So it may be too early to say, but it’s certainly something that can be considered.”

Helga Komen, MD, an instructor in anesthesiology at Washington University in St. Louis, was not surprised by the findings. “In fact, we recently concluded a couple of studies where we compared intraoperative methadone with fentanyl/hydromorphone for outpatient [Anesth Analg2019;128(4):802-810] and inpatient surgical procedures, and obtained very similar results,” Dr. Komen said.

“Dr. Cheriyan’s results and our results are very important to show our colleagues the efficiency and safety of this long-acting opioid, and to encourage them to use it more,” Dr. Komen added. “Having an opioid on hand that is highly effective in treating intraoperative and postoperative pain is a choice that shouldn’t be forgotten in everyday practice, especially given the current opioid crisis where we want our patient to have the least possible opioid consumption, with no or little adverse events.

“Of course, we will always need more evidence exploring methadone’s pharmacokinetics, as well as its use in outpatient surgeries and in patients with obstructive sleep apnea,” she added.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.