Author: Michael Vlessides

Anesthesiology News

A comprehensive study has yielded potentially alarming findings regarding the ease with which the hepatitis C virus (HCV) can be transferred from sterile needles and syringes into medication vials if the diaphragm is already contaminated. The study also found that common vial-cleaning practices are not enough to eliminate HCV infectivity.

The impetus for the trial was a 2014 hepatitis C outbreak at several Ontario colonoscopy clinics. Subsequent investigations pinpointed contaminated medications—administered by anesthesiologists—as the source of the outbreak.

“In these cases, anesthesiologists denied reusing needles and syringes, although they did admit to sharing medications that were accessed with sterile needles and syringes,” said Janet M. van Vlymen, MD, an associate professor of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at Queen’s University, in Kingston, Ontario.

“So, we wondered whether a similar mechanism may be accounting for the problems that we’re seeing with these types of hepatitis C outbreaks,” she said. “Perhaps poor hand hygiene practices are actually causing contamination on the outside of the medication vials that are accessed with sterile needles and syringes.”

High Infectivity

The investigators hypothesized that when caring for HCV-infected patients, anesthesiologists may inadvertently contaminate the medication vial’s diaphragm; subsequent access with sterile needles and syringes might transfer the virus into the medication, where it remains stable in sufficient quantities to infect subsequent patients.

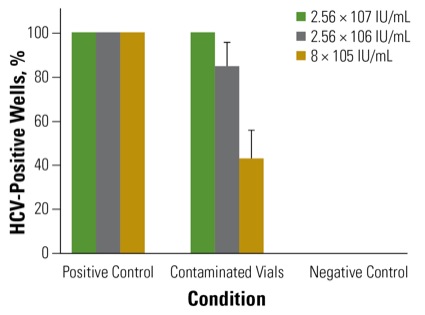

To examine this possibility, Dr. van Vlymen and colleagues Melanie Jaeger, MD, and Selena Sagan, MD, undertook a multiphase trial that began with simulated contamination of multidose medication vials containing cell culture media. The vials’ rubber access diaphragms were contaminated with 33 mcL of three different titers of HCV stock: 2.56 × 107, 2.56 × 106, or 8 × 105IU/mL, representing high, intermediate and low titers, respectively.

“We chose 33 mcL because it’s previously been shown to be the volume of an inadvertent and unrecognized contamination,” Dr. van Vlymen said. Once this was dry, the vials were punctured five times with a sterile needle and syringe, and their contents analyzed using both focus-forming unit (FFU) assay and real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay at five days after infection.

This part of the study found that all three concentrations of HCV were able to contaminate the vial contents sufficiently to initiate an infection in cell culture. Contamination rates were 100% in the high-titer HCV samples, 85% in the medium-titer HCV samples, and 43% in the low-titer samples (Figure). “Taken together, these results suggest that dry hepatitis C can be efficiently transferred from the surface of medication vials into cell cultures,” Dr. van Vlymen said.

The second part of the study sought to determine whether HCV remains viable over time in commonly used medications in sufficient quantities to initiate an infection, using similar infection protocols on the outside of the vials. Medications included dexamethasone, lidocaine, neostigmine, phenylephrine, propofol and rocuronium. HCV stocks were diluted 1:10 in each of these medications or saline, then incubated at room temperature and tested for infectivity at various time points for up to 72 hours.

The analysis found that each of the medications was able to support live virus throughout the test period. “Phenylephrine was particularly good at supporting HCV,” Dr. van Vlymen said, “with dexamethasone and lidocaine a little less so. But in all of them, the virus was stable and infectious for up to 72 hours.”

Cleaning Practices Unsuccessful

Finally, the researchers examined the effect of common cleaning practices on the eradication of HCV infectivity. Rubber diaphragms were contaminated with HCV and then cleaned with 70% isopropyl alcohol swab using one of three techniques: a single wipe; a two- or three-second wipe; or a 10-second wipe with friction, with or without drying. Next, the rubber diaphragms were each rehydrated in cell culture media, which was used to infect human hepatoma cells.

As Dr. van Vlymen reported at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (abstract A1179), a single wipe of the diaphragm with 70% isopropyl alcohol was not sufficient to eliminate HCV infectivity. Neither the single wipe nor the two-second/three-second wipes—both with and without drying—were sufficient to eliminate hepatitis C infectivity.

In contrast, the 10-second wipe dramatically reduced the risk for contamination, although even that did not completely eliminate HCV infectivity in all replicates.

These findings, Dr. van Vlymen stressed, demonstrate the importance of changing practices with respect to the administration of medications. “In one recent survey, 80% of people believe there is no potential infectious risk if a clean needle and syringe are used,” she said. “Most of the time people reported either visually inspecting the top of the vial, or a one-swipe clean with alcohol, both of which we’ve shown to be insufficient.”

The researchers went on to recommend significant investment in education across medical specialties regarding the division or elimination of multidose vials to help minimize the spread of nosocomial HCV infections. “Both the CDC and ASA have guidelines that recommend that multidose vials be used for a single patient whenever possible,” she explained. “They go on to say that in circumstances where they are used for more than one patient, they should not be in the immediate patient care area, including the operating room.”

The presentation caused a lively discussion by Dr. van Vlymen’s audience. “This is a terrific study and I’m fascinated by your findings,” commented Vikas N. O’Reilly-Shah, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of anesthesiology at Emory University, in Atlanta. “So, rather than one vial for one patient, would we be better off with pre-aliquoting or assuring at the time that medications are drawn that they’re all drawn off, maybe by pharmacy? Would that potentially address the situation?”

“The idea of having hospital pharmacists prepare single aliquots of medications can help,” Dr. van Vlymen replied, “as well as advocating to pharmaceutical companies to prepare medications in single-unit dosing and simply being knowledgeable about those risks. I think the problem is that there are many patients where we would otherwise have tremendous amount of waste, particularly in pediatric populations, and physicians are simply trying to minimize waste.”

“Do you think there’s a role for checking other surfaces within the operating room for hepatitis C or other pathogens when cleaning operating rooms?” asked session co-moderator Grant C. Lynde, MD, MBA, an associate professor of anesthesiology at Emory University. “And what do you see as the other potential sources of infection?”

“It’s interesting when you observe with the eyes of an infection-control practitioner,” Dr. van Vlymen said. “I think we often have a false sense of security in the operating room that it’s a sterile environment, but there’s nothing sterile about the environment in which we work.

“In the end, I think it starts with a higher level of vigilance,” she said. “We need to make sure we are taking infection control steps throughout the entire process. Personally, I am absolutely vigilant that nobody touches my cart without using hand hygiene beforehand.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.