Author: Michael Vlessides

Anesthesiology News

Day-of-surgery administration of 6 L or more of intraoperative fluid is associated with perioperative morbidity across a variety of measures, according to a database analysis by a multicenter research team. In addition, the analysis concluded that the primary driver of fluid administration levels was hospital practice, and not patient- or disease-based factors.

“The anecdotal experience that many of us have seen in the field is actually showing up in the data,” said Thomas J. Hopkins, MD, MBA, an anesthesiologist at Duke Health, in Durham, N.C. “There are some hospitals that are following a more regimented approach with how we think about fluids, and other hospitals that are not.”

Dr. Hopkins, the lead author of the study, told Anesthesiology News that as seen in earlier work, this dichotomy in fluid management directly affects patient outcomes. “What we’ve seen in the literature on this is that if you use an individualized approach that leverages some type of noninvasive technology to guide you based on what the patient’s needs are, rather than a standardized equation, [then] you end up giving less fluid overall.

To investigate this question further, the researchers used four years of data (2013-2016) from the Truven administrative database, which represents 6.6% of U.S. hospitalizations, according to the researchers.

Higher Fluid Administration Meant More Adverse Outcomes

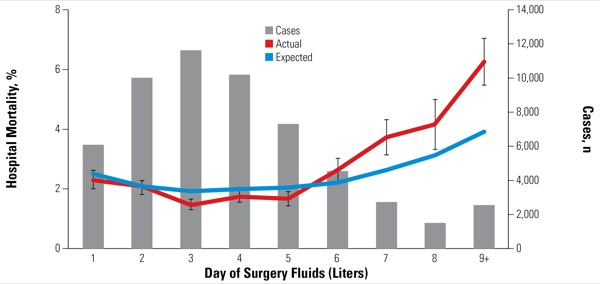

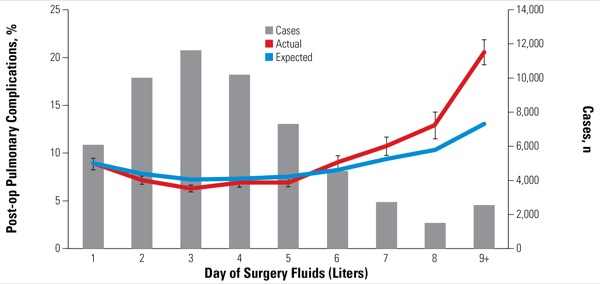

The researchers adjusted for potential confounders using a day-of-surgery fluid propensity model composed of variables that might predispose individuals to receive fluid during surgery, including patient characteristics and disease management factors. They also characterized hospitals according to their fluid use: low (mean day-of-surgery fluid, <3 L), medium (3.0-4.99 L) or high (≥5 L). Additional risk models were constructed for hospital mortality (Figure 1), postoperative pulmonary complications (Figure 2), postoperative cardiac complications, any postoperative complications and hospital length of stay. The final data set included 56,645 patient discharges (mean age, 63.9 years; 54.2% female) from 128 hospitals.

The mean day-of-surgery fluid use for the entire cohort was 4.1 L, and 20.1% of patients received at least 6 L. But the proportion of patients receiving 6 L or more of fluid on the day of surgery varied greatly by institution. Only 3.8% of cases at low-fluid hospitals (38% of hospitals) received that amount, compared with 46.7% of patients at high-fluid hospitals (23% of hospitals).

“When taken in combination with all the propensity matching we did to try to correct for patient morbidity and surgical complexity, [this] tells you that the practice in the hospital is what drives the amount of fluid that folks get on the day of surgery,” Dr. Hopkins said, adding that the findings provided “anecdotal experience that some hospitals are transitioning to more goal-directed approaches that leverage dynamic hemodynamic monitoring and other hospitals are still kind of doing things the way that we were doing when I was a resident.”

The analysis also found that higher fluid administration rates were associated with adverse patient outcomes. Most notably, actual mortality rates were significantly higher than expected among patients who received day-of-surgery fluid administration of 6 L or more (P<0.05; Figure 1). For example, patients receiving 6 L of fluid on the day of surgery had an observed hospital mortality rate 38% higher than expected (3.9% vs. 2.8%; P<0.0001). The observed difference between actual and expected mortality rates grew incrementally from there.

The difference—found across all patient-, disease- and surgery-related subgroups—was also seen in postoperative pulmonary complications (P<0.0001; Figure 2), postoperative cardiac complications (P<0.001), any postoperative complications (P<0.001), and length of stay (additional 0.65 days per patient; P<0.001).

“So now we know that more than 6 L of fluid can be risky for the patient, and we know that some hospitals are doing that more than others,” Dr. Hopkins said.

Nevertheless, as reported at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (abstract A1191), the researchers were quick to note that these results don’t necessarily warrant limiting fluid administration. “When we look at these data and see an increased risk of complications at the high end of the fluid administration scale, one thought could be that we should just fluid restrict,” said Jennifer Sahatjian, PhD, a co-author of the study and director of clinical research at Cheetah Medical, in Newton, Mass. “But we also saw increased lengths of stay at the low fluid volumes as well, suggesting that under-resuscitation can also involve patient complications, she added, citing the RELIEF study, which showed an increased risk for acute kidney injury and surgical site infections in the restrictive fluid therapy group (N Engl J Med 2018;378[24]:2263-2274).

“Did you adjust for the duration of surgery?” asked Eric Rosero, MD, an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

“Yes, we did,” Sahatjian replied. “We adjusted for many factors in the propensity model to make sure we had clean results.”

“How do you know that the excess fluid administration is not just a marker for intraoperative hypotension?” asked Richard H. Epstein, MD, a professor of clinical anesthesia at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “The association between even a few minutes of intraoperative hypotension and mortality is strong.

“Of course, the data set won’t have intraoperative blood pressure measurements,” Dr. Epstein said. “But you might be able to look at administration of drugs, such as phenylephrine and ephedrine, as a surrogate for intraoperative hypotension.”

“That’s exactly what we were trying to adjust for in our patient propensity model,” Sahatjian replied. “We were looking at diagnosis.”

In the end, the researchers believe these findings may help institutions reduce mortality rates by taking a different perspective in fluid management. “We think this emphasizes the importance of having a goal-directed approach so we can find the optimal area that’s patient-centric,” Sahatjian said. “And now we have the tools and measurements to help guide us.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.