Author: Michael Vlessides

Anesthesiology News

Anesthesiology has long valued the aviation industry’s adherence to strict safety protocols. Now, researchers have employed a modified crew resource management tool to help residents identify hazardous attitudes and their potentially negative effects during perioperative crises.

“Crew resource management is a systemization of crisis management,” said Adam Schiavi, PhD, MD, an assistant professor of anesthesiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in Baltimore. “It’s taking the best and the worst of human personalities and analyzing how that instinct comes out in crisis situations, and then modifying it. So you can actually train instinctual behavior using these methods.”

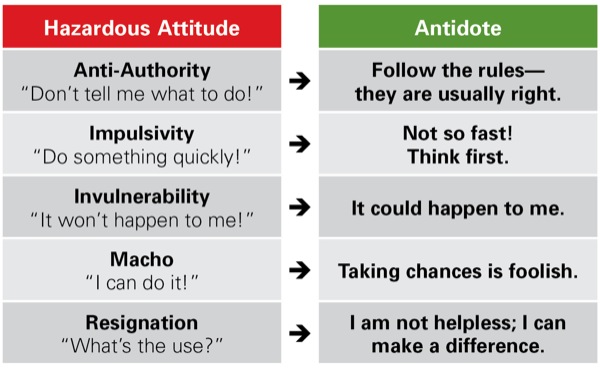

To help apply such techniques into anesthesia training, Dr. Schiavi—along with colleagues Christina Miller, MD, and Robert S. Greenberg, MD—modified the Federal Aviation Administration’s Hazardous Attitudes Survey scenarios to reflect perioperative crises. According to the survey, five hazardous attitudes can lead to team failure in a crisis:

- invulnerability

- anti-authority

- macho

- impulsivity

- resignation (Table)

“All of these attitudes have a positive aspect that is necessary for us to do our jobs,” said Dr. Miller, an assistant professor of anesthesiology at Johns Hopkins. “But it’s when one particular characteristic takes over in a detrimental way that things can get derailed in a crisis situation.”

Participants in the program began by taking the survey, wherein they were presented with 20 clinical scenarios where a critical decision had been made. Each scenario was followed by five hazardous attitudes as the possible foundation for the decision. The participants then ranked the five options from most to least likely in reflecting their motivation to have made such a decision.

Invulnerability More Likely in Women

At the end of the self-assessment, the five attitudes were named and described, and participants were asked to rank them in order of most to least likely to affect their clinical decision making. The participants then received immediate analyses of their responses and were familiarized with the five attitudes, which were subsequently discussed during a hands-on workshop facilitated by the investigators.

“The entire program is designed to be self-reflective, so the residents can recognize when they’re displaying an attitude in a harmful way or recognize if they’re being subjected to a bias,” Dr. Schiavi explained.

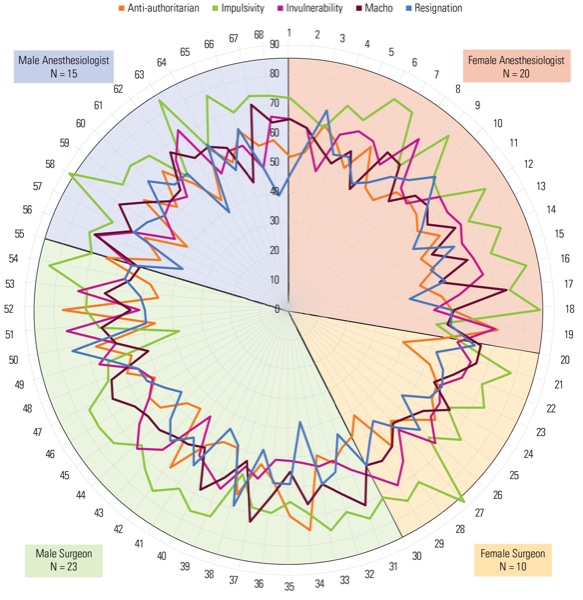

After taking the survey, the 66 participants (36 men and 30 women, including 34 anesthesiology and 32 surgery residents) then participated in a series of workshops comprising small group discussions and role-playing of the various attitudes in clinical scenarios. These workshops allowed participants to identify and confront the hazardous attitudes that may impede teamwork in the OR.

As Drs. Schiavi and Miller reported at the 2019 annual meeting of the International Anesthesia Research Society (abstract D141), the most prevalent attitude demonstrated by the group was impulsivity, followed by invulnerability, macho, anti-authority and resignation. Of note, there was no difference in the distribution of attitudes between specialties.

The investigators also analyzed attitudinal differences by sex, finding that women were significantly more likely to have higher mean invulnerability scores. Men, on the other hand, demonstrated a trend toward higher mean macho scores (Figure).

Also of interest, residents’ self-perceptions of their predominant attitude correlated poorly with the predominant attitude identified by the test.

“That’s why we need the workshop,” Dr. Miller said.

Although the researchers have yet to formally assess the ability of the program to change behaviors and improve OR effectiveness, they were nevertheless encouraged by what they’ve seen so far.

“Half the groups did the workshop first and then the OR simulation, and the other half did the OR simulation first and then the workshop,” Dr. Miller said. “And anecdotally, we saw that if they had done the workshop first—which focused on communication and getting to know people and recognizing bad attitudes in a crisis—then they communicated a lot better during the simulation.”

Formal results notwithstanding, both Drs. Miller and Schiavi believe that programs such as these have a potential place in all medical training. “Having people recognize which responses are appropriate and which are inappropriate is important,” Dr. Miller said. “Also, making people realize that these responses correspond with a broader personality or hazardous attitude type is equally important.

“Finally, having the opportunity to practice with others and recognize how these attitudes are played out in simulated scenarios was very helpful,” she added.

Clyde Matava, MD, an assistant professor of anesthesia and the director of eLearning and Technological Innovations at the University of Toronto, saw the potential in the program. “I think it’s very useful. As a self-reflection tool, it’s good to see how one’s own character traits might impede a lot of the big issues we face in the operating room, especially in crisis situations.

“Because as we know, communication and team performance correlate with patient outcomes,” Dr. Matava continued. “So being able to reflect on our role as a team player is a big part of that success.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.