A database analysis comprising more than 25,000 patients has concluded that the STOP-BANG questionnaire has cross-sectional construct validity, in that greater proportions of patients with intermediate and high STOP-BANG risk scores had known diagnoses of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Despite this positive finding, the study also revealed that STOP-BANG risk strata had only weak correlations with other patient health and comorbidity indexes, and had low predictive validity for mortality, cardiac complications or lengths of stay after adjusting for patient comorbidities and surgical factors.

STOP-BANG is the acronym for a series of questions on the following elements: snoring, tired, observed (i.e., stopped breathing or gasping during sleep), pressure (i.e., high blood pressure), body mass index (>35 kg/m2), age (>50 years), neck size and gender (i.e., male).

“The focus in perioperative medicine and respiratory conditions has recently shifted toward obstructive sleep apnea, which poses the perioperative physician with interesting challenges, both in terms of diagnosis and management,” said Ashwin Sankar, MD, a resident at Mount Sinai Hospital at the University of Toronto. “Although there is some evidence of association between STOP-BANG scores with respiratory complications, there have been inconsistent associations between STOP-BANG and other nonrespiratory outcomes.

“At our institution, we have been collecting STOP-BANG data prospectively since 2011,” he added. “So we set out to determine the validity of the STOP-BANG questionnaire.” Specifically, Dr. Sankar and his colleagues wanted to evaluate:

- the cross-sectional construct validity using proportions of patients with known OSA among STOP-BANG risk strata;

- concurrent construct validity using correlations between STOP-BANG risk strata and the ASA’s physical status classification, Revised Cardiac Risk Index and Charlson Comorbidity Index; and

- predictive criterion validity using adjusted associations of STOP-BANG risk strata with 30-day in-hospital mortality, major cardiac complications and hospital length of stay.

The investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients undergoing major, elective noncardiac surgery at the institution between 2008 and 2015. Patients underwent a variety of surgical procedures with a median duration of two hours; most were performed under general anesthesia. STOP-BANG scores from the preoperative clinic were used to sort patients into low-, intermediate- or high-risk strata.

Validation for Sleep Apnea

The study cohort consisted of 26,068 patients. “With respect to STOP-BANG strata, low-risk patients were assigned scores of 0-2, intermediate risk scores were 3-4, and high risk was either 5 or greater or specific constellations of high-risk features,” Dr. Sankar explained.,This resulted in 15,126 patients (58%) at low, 6,056 patients (23%) at intermediate and 4,886 patients (19%) at high risk, according to STOP-BANG.

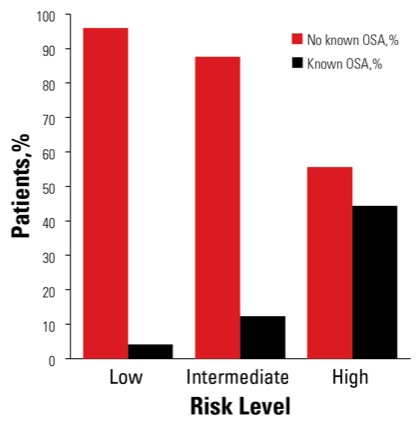

Regarding the questionnaire’s cross-sectional construct validity, 4% (n=615) of the low-risk stratum had a known OSA diagnosis, compared with 12% (n=740) of the intermediate-risk stratum and 44% (n=2,142) of the high-risk stratum (Figure). “This suggests that the STOP-BANG questionnaire was doing what it’s supposed to,” Dr. Sankar said.

Results were not nearly as strong for concurrent construct validity. Weak but statistically significant (P<0.001) correlations were observed between STOP-BANG risk strata and ASA physical status classification (correlation coefficient, 0.28), Revised Cardiac Risk Index (correlation coefficient, 0.24) and Charlson Comorbidity Index (correlation coefficient, 0.10). Analysis of predictive criterion validity revealed that STOP-BANG risk strata were not associated with 30-day mortality, cardiac complications or hospital length of stay (P>0.05) after adjusting for patient and surgical factors.

“Interestingly, our analyses showed that the STOP-BANG score was associated with outcomes when we did not adjust for any other covariates,” Dr. Sankar said at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (abstract BOC07). “But when we conducted adjusted analyses, STOP-BANG was no longer associated with any of the outcomes, suggesting that the associations we observed in unadjusted analyses were largely driven by known risk factors.”

The analysis was limited by the availability of data, Dr. Sankar noted. “In particular, our database did not capture respiratory complications very well, and we’d actually expect that STOP-BANG is likely associated with these complications.” Neck circumference also was not captured systematically at one study site, although subsequent sensitivity analyses with complete data did not markedly change the initial results.

“In conclusion,” Dr. Sankar said, “the STOP-BANG questionnaire is clearly measuring what it’s supposed to measure, which is OSA. In fact, undiagnosed OSA was likely common in the intermediate- and high-risk STOP-BANG strata. The low concurrent construct validity we observed with ASA classification, Revised Cardiac Risk Index and the Charlson Comorbidity Index perhaps suggests that STOP-BANG was measuring a different, perhaps more respiratory, construct.

“Finally, the fact that the associations we found between STOP-BANG and outcomes in unadjusted analyses diminished after adjusting for known patient and surgical factors suggests that the association of STOP-BANG with nonrespiratory outcomes was largely explained by known risk factors,” he said.

Some of Dr. Sankar’s audience members questioned how to turn these results into clinical practice, including Ashish Khanna, MD, an assistant professor of anesthesiology and the vice chief of critical care research at the Cleveland Clinic, in Ohio. “I’m especially interested because about two years ago, we published a study where we looked at the association between increasing STOP-BANG score with the incidence of hypoxemia,” he said, “and we found no association at all. In our large cohort, we concluded that the STOP-BANG score does not predict for hypoxemia events after noncardiac surgery. In other words, hypoxemia was common after noncardiac surgery; however, the STOP-BANG score could not be used as a predictor.

“So, given what you’ve presented here, what would you say is the clinical utility of the STOP-BANG score beyond it being a robust and valid screening tool?” Dr. Khanna asked. “What does a higher number mean to a perioperative physician? What should I do with my patients?”

“I think we can say that based on our study, STOP-BANG is associated with a diagnosis of OSA,” Dr. Sankar replied. “With respect to associations of STOP-BANG scores with outcomes, the literature is mixed but has suggested that it is associated with respiratory complications, so perhaps monitoring those patients for these specific complications is prudent.

“We believe the current study ultimately suggested that associations of STOP-BANG with the outcomes examined—mortality, cardiac complications and length of stay—were explained by known risk factors,” he added.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.