Anesthesiology News

Case Presentation

An 83-year-old woman was brought to the emergency department by emergency medical technicians after a fall, presenting with a blunt injury to the face with multiple visible injuries to the nose and lip and severe active bleeding from her mouth. Her cervical spine was immobilized by a cervical collar. Upon arrival, her Glasgow Coma Scale score was 6; blood pressure, 160/99 mm Hg; heart rate, 120 beats per minute; and oxygen saturation, 84% with 6 L of oxygen administered via a non-rebreather face mask. Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, coronary artery diseas e and atrial fibrillation. She was treated with metoprolol, lisinopril and warfarin.

The cervical collar was removed, and the patient’s head and neck were maintained in neutral position by manual in-line stabilization. Preparations were made by the surgical team to perform emergent cricothyroidotomy. The attending anesthesiologist attempted intubation by video laryngoscopy using a GlideScope (Verathon). No view of the glottic opening could be obtained because of continuous severe bleeding. An Intubating Laryngeal Mask Airway (ILMA; LMA Fastrach; Teleflex) size 4 was inserted successfully on the first attempt. A lubricated, reinforced 7-mm endotracheal tube (ETT) was passed through the ILMA and intubation confirmed by capnography. The ILMA was then removed while the ETT was retained in place. The patient was transferred to the ICU. Her international normalized ratio was 3; prothrombin complex concentrate was administered to reverse the warfarin effect. Oropharyngeal bleeding subsequently stopped, the facial lacerations were sutured, and the patient was successfully extubated after 48 hours.

Discussion

Traumatic upper airway injury resulting in severe oropharyngeal bleeding is a potentially life-threatening emergency. Active oral bleeding can obscure the visualization of the anatomic structures, including the laryngeal inlet, leading to an airway crisis, especially if the patient needs to be intubated urgently. Direct, indirect (video) laryngoscopy, and fiber-optic–guided intubation may all be ineffective in this situation. Emergency front-of-neck access (FONA) is indicated if laryngoscopy is predicted to be unsuccessful.

Other methods for securing the airway in patients presenting with active oral bleeding are intubation through a supraglottic airway device (SAD), retrograde intubation and lightwand-guided intubation, to name a few.1

A number of SADs are specifically designed to serve as a conduit for endotracheal intubation and can be especially useful in these situations.2 They include the ILMA, i-gel (Intersurgical), intubating laryngeal tube iLTS-D (VBM Medizintechnik), air-Q (Cookgas), and the Aura-I (Ambu) and AuraGain (Ambu).

Intubating Laryngeal Mask Airway

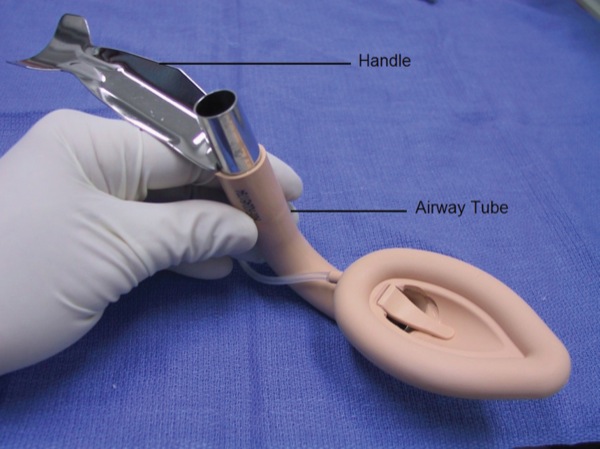

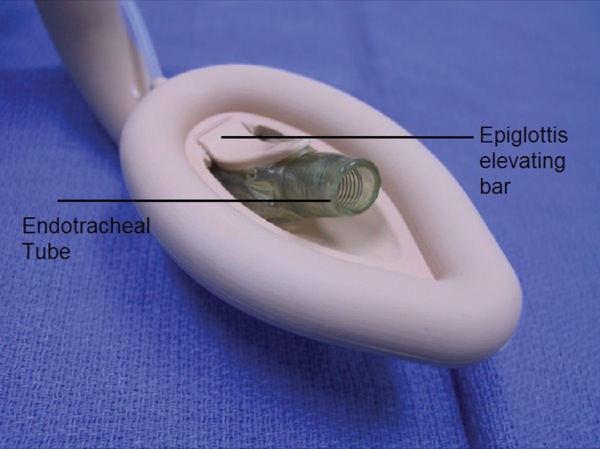

The LMA Fastrach (ILMA) is a variant of the original Laryngeal Mask Airway and was introduced to clinical practice by Dr. Archie Brain in 1997. It has a curved, rigid, stainless steel airway tube with a guided handle, an epiglottic elevating bar, and a guiding ramp to direct the ETT to the laryngeal inlet.2 (Figures 1 and 2). It can be used for ventilation and provides the ability to intubate the trachea blindly or guided by a flexible bronchoscope. The LMA Fastrach is available in three sizes (3, 4 and 5) as a single-use or reusable device (up to 40 uses).3

The LMA Fastrach is inserted with the patient’s head in the neutral position.4 If ventilation is not optimal, the positioning of the ILMA can be adjusted to achieve a better alignment of the ventilation aperture with the glottic opening. The most popular optimization maneuvers are known as the Chandy maneuver, named after Dr. Chandy Verghese. The LMA Fastrach’s handle is moved horizontally and in a sagittal plane until achieving the least resistance to ventilation, followed by lifting the handle away from the posterior pharyngeal wall.5

Ferson et al reported successful insertion of the LMA Fastrach in 100% of patients with expected difficult airways, after a maximum of three attempts. Blind insertion of an ETT through the LMA Fastrach was successful in 97% of patients, and fiber-optic–guided intubations were successful in 100% of patients.6

The LMA Fastrach has been used effectively to intubate the trachea when the patient’s head and neck are maintained by in-line stabilization and in patients wearing a rigid collar.7,8 Komatsu et al reported effective ventilation with the LMA Fastrach in 90% of patients wearing a rigid collar and successful blind intubation in 96% of those patients.8

Totaltrack

The Totaltrack VLM (Medcomflow) is a new device combining the features of the laryngeal mask device and the video laryngoscope. It allows for simultaneous ventilation and intubation under continuous visualization of the glottic opening. Uninterrupted ventilation during tracheal intubation is achieved through a preloaded ETT into the ventilation channel. Gastric drains allow for gastric decompression and drainage of gastric contents. In a recent study, Gomez-Rios et al reported its successful use in 300 patients with a successful first-attempt insertion rate of 83% and successful first attempt endotracheal intubation rate of 85%. Optimization maneuvers to improve glottic visualization during intubation were necessary in 26% of cases.9

Lighted Stylets

Lighted stylets can be used for blind intubation by transillumination of the soft tissues of the anterior neck.10

Retrograde Intubation

Retrograde intubation can be performed using several techniques, including an epidural catheter and a Tuohy needle, a long venous catheter and intravenous cannula, or the Cook Retrograde Intubation Set (Cook Medical).1,10 Retrograde intubation involves puncturing the subglottic airway with a needle and then threading a guidewire retrograde through the glottis opening. The guidewire is then used to railroad an ETT into the trachea.

Conclusion

Anesthesiologists should be proficient in alternative airway techniques and be ready to use them in case of a bleeding airway when visualization of the glottic opening is not possible.

References

- Kristensen MS, McGuire B. Managing and securing the bleeding upper airway: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67(1):128-140.

- Gordon J, Cooper R, Parotto M. Supraglottic airway devices: indications, contraindications and management. Minerva Anestesiol. 2018;84(3):389-397.

- Brain AI, Verghese C, Addy EV, et al. The intubating laryngeal mask. I: development of a new device for intubation of the trachea. Br J Anaesth.1997;79(6):699-703.

- https://www.teleflex.com/ usa/ en/ product-areas/ military-federal/ airway-management/ supraglottic-airways/ index.html. Accessed January 6, 2020.

- Hernandez MR, Klock PA Jr, Ovassapian A. Evolution of the extraglottic airway: a review of its history, applications, and practical tips for success. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(2):349-368.

- Ferson DZ, Rosenblatt WH, Johansen MJ, et al. Use of the intubating LMA-Fastrach in 254 patients with difficult-to-manage airways. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(5):1175-1181.

- Asai T, Murao K, Tsutsumi T, et al. Ease of tracheal intubation through the intubating laryngeal mask during manual in-line head and neck stabilisation. Anaesthesia. 2000;55(1):82-85.

- Keller C, Brimacombe J, Keller K. Pressures exerted against the cervical vertebrae by the standard and intubating laryngeal mask airways: a randomized, controlled, cross-over study in fresh cadavers. Anesth Analg. 1999;89(5):1296-1300.

- GÓmez-RÍos MÁ, Freire-Vila E, Casans-FrancÉs R, et al. The TotaltrackTM video laryngeal mask: an evaluation in 300 patients. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(6):751-757.

- Langeron O, Birenbaum A, Amour J. Airway management in trauma. Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75(5):307-311.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.