Author: Michael Vlessides

Anesthesiology News

When it comes to medication errors in general anesthesia, more clinicians than ever are reporting their experiences in studies and case reports, according to a systematic review by a Canadian research team. Yet these errors continue, and sometimes with fatal effects.

“We all know that medication errors occur everywhere in medical practice,” said Amir Abrishami, MD, FRCPC, a staff anesthesiologist at Niagara Health and an assistant professor of anesthesia at McMaster University, in Hamilton, Ontario. “But I feel the stakes are higher in the perioperative setting because anesthesiologists usually work alone, and the drugs we work with can have immediate effects on cardiovascular, respiratory or central nervous system function. That’s why we feel it’s important to take these errors seriously and be aware of the different types of effects they can cause.”

To help get at the root of this issue, Dr. Abrishami and his colleagues systematically searched MEDLINE (from 1946 to the present) for narrative reviews, case reports and case series that reported medication errors in adult patients who underwent general anesthesia. Non–English-language studies and pediatric studies were excluded. Medication errors were defined as unintentional use of a medication—such as wrong type, dose, route or time—that either caused or could have caused patient harm.

“The problem with performing this type of systematic review is that it’s very difficult to do a specific literature search,” Dr. Abrishami said. “That’s why we think there are so few systematic review articles on the subject.”

Presenting at the 2018 annual meeting of the International Anesthesia Research Society (abstract PS52), the researchers revealed that after reviewing 3,705 citations, 31 reviews and 20 case studies were found eligible for inclusion in the review. As the Table illustrates, the number of studies that reported medication errors has increased markedly over the past two decades.

| Table. Increase in Number of Medication Error Articles Over Time | |

| Period | No. of Medication Error Articles Published |

|---|---|

| 1990-1993 | 4 |

| 1994-1997 | 1 |

| 1998-2001 | 6 |

| 2002-2005 | 14 |

| 2006-2009 | 6 |

| 2010-2013 | 15 |

| 2014-2017 | 9 |

| The total number of studies (N=55) doesn’t match the total number included in the review (n=51), as four studies without full text or in non-English language were excluded from the review but included in the tally. | |

“This trend of publishing more papers might be the result of people becoming more aware of medication errors or more willing to publish their case reports,” Dr. Abrishami said.

Certain Drugs Lead to Certain Errors

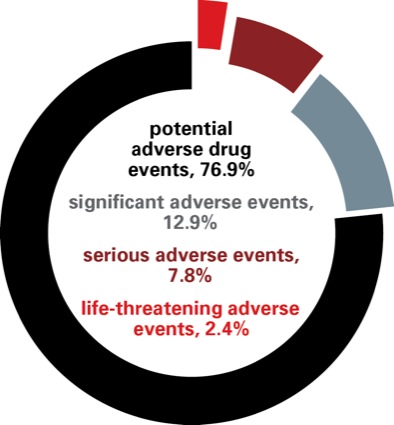

Overall, medication errors led to four different outcomes. The most common was potential adverse drug events (76.9% of errors), followed by significant adverse events (12.9%); serious adverse events, such as permanent disability (7.8%); and life-threatening adverse events (2.4%).

The analysis also revealed that the most common medications involved in errors were narcotics, vasopressors and antibiotics. The most frequent types of reported errors included dosing mishaps, followed by substitution, as in giving one drug instead of another; preparation, such as an improperly diluted drug; and administration, such as wrong route errors.

The researchers also found that certain medications were more frequently involved in certain types of errors than others. For example, phenylephrine was frequently involved in substitution errors, whereas narcotics were more commonly found in administration and preparation errors.

“It’s insightful to know that different types of errors can happen in different ways, depending on the type of medication in question,” Dr. Abrishami said. “This kind of information can help us develop strategies to deal with these issues.”

Such strategies, Dr. Abrishami added, may ultimately help to reduce medication errors in patients undergoing anesthesia. “My next step would be looking at clinical review articles on strategies to reduce medication errors and see how effective they are,” he said. “The answer could lie in electronic dispensing machines, double-checking strategies, or coming up with a checklist system.

“It’s a very broad topic,” he concluded, “but I think if we can outline and summarize the different types of strategies that different people have used effectively, we may be able to reduce medication errors.”

Session moderator Jose C. Humanez, MD, an assistant professor of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital, noted that the study had some remarkable points, including the increase in error reporting noted after 2001, shortly after the release of the “To Err Is Human” report from the Institute of Medicine. “Many health care systems had a shift to the culture of safety at that point, and started looking more deeply into the ‘holes’ in the process that led to errors,” he said.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.