Author: Chase Doyle

Anesthesiology News

Opioid dosage after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) did not correlate with development of persistent use at six weeks, but the duration of those prescriptions was associated with chronic opioid dependence, according to a new study.

Based on these results, researchers noted that evidence of certain risk factors should guide a provider’s decision to refill an opioid prescription six weeks or more after uncomplicated TKA. Even in the presence of risk factors, the authors emphasized that uptitration of opioids in the immediate postoperative period was not necessarily associated with later opioid misuse.

As Dr. Pace reported, surgery itself has been shown to be a significant risk factor for the development of chronic opioid dependence (JAMA Surg 2017;152[6]:e170504). In TKA, one of the most common surgeries in the United States, the prevalence of persistent opioid use after surgery is 8.2% at six months (Pain 2016;157[6]:1259-1265) and 1.41% at 12 months among opioid-naive patients (JAMA Intern Med 2016;176[9]:1286-1293). However, as she noted, it is currently unknown whether consuming larger amounts of opioids in the acute postoperative period correlates with persistent use.

For this study, Dr. Pace and her colleagues screened patients aged 18 to 90 years presenting for unilateral, primary TKA. Patients who were discharged to a rehabilitation facility or taking more than 30 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) at the time of surgery, and those who experienced surgical complications in the first six postoperative weeks, were excluded from the analysis. Using the electronic health record (EHR), researchers collected total opioid consumption from postoperative day 1 to two weeks.

Patients who did not refill a prescription after discharge were contacted by telephone at two weeks to confirm discontinuation of opioid use, whereas those who requested a refill at or before their two-week visit were assumed to have consumed all opioid prescribed to them at discharge, said Dr. Pace. Patients who requested a refill at their six-week visit were identified as still consuming opioids. Finally, the EHR was used to identify risk factors for persistent postoperative opioid use, which included a current prescription for benzodiazepines or antidepressants, a history of drug or alcohol abuse, and current tobacco use.

Risk Factors and Persistent Opioid Use

At the 2019 annual meeting of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA), Dr. Pace reviewed the data collected from 220 subjects. Results showed that 47 patients (21%) stopped using opioids before two weeks (group 1); 138 (63%) were consuming opioids at two weeks but not at six weeks (group 2); and 35 (16%) were using opioids at six weeks (group 3).

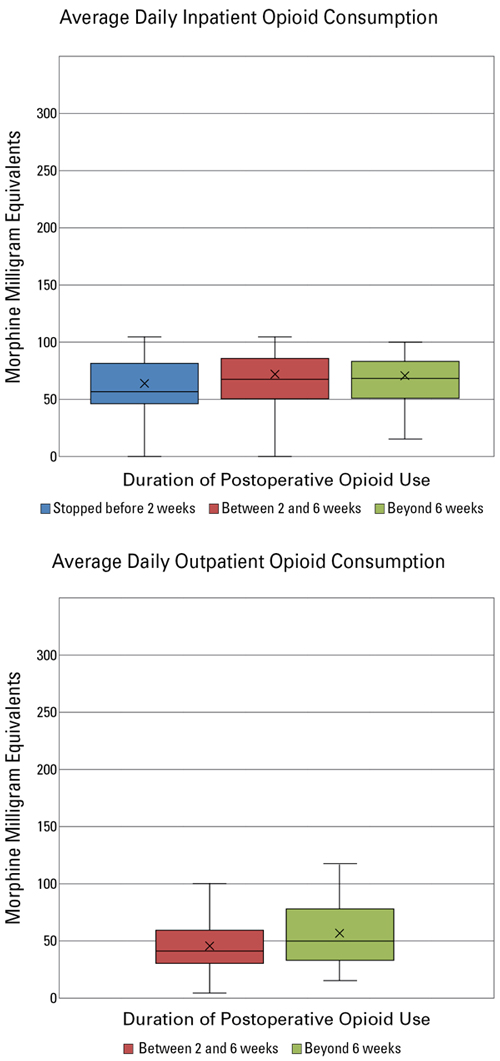

More importantly, Dr. Pace said, the average daily inpatient opioid consumption did not differ significantly among the three groups (32.3, 41.1 and 43.2 MME, respectively; P=0.14). Similarly, the average daily outpatient opioid consumption of group 2 and group 3 did not differ significantly (46.8 vs. 55.9 MME, respectively; P=0.11) (Figure 1).

“This is important for acute pain providers to understand, that we can potentially uptitrate patients in the immediate postoperative period to adequately treat their pain without putting them at risk for developing chronic opioid use later,” Dr. Pace said. “Having to prescribe patients slightly higher doses in the short term probably has more to do with how individual patients metabolize these drugs rather than opiate misuse.”

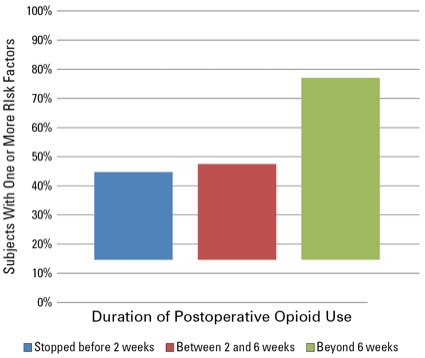

What can set patients up for misuse later, however, is the continued prescription of opioids more than six weeks after surgery. Although the presence of risk factors for persistent opioid use after surgery did not differ significantly between subjects in group 1 and those in group 2, subjects in group 3 were significantly more likely to have at least one risk factor compared with group 1 (P=0.003) and group 2 (P=0.001), the authors noted (Figure 2).

“If you’re going to refill beyond six weeks, that’s when you should start paying attention,” Dr. Pace said. “Patients who were still using opioids beyond the immediate postoperative period were far more likely to have a history of drug and/or alcohol abuse and be taking antidepressants or antianxiety medication. It was off-the-charts significant.”

Dr. Pace and her colleagues plan to use this finding to develop an EHR checklist to aid pain medication prescribers in the postoperative period.

Responding to the Opioid Epidemic

Adam Sassoon, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, in Santa Monica, Calif., said patients who have had previous opioid therapy before their surgery often have the hardest time transitioning away from opioids, especially following revision procedures. Dr. Sassoon also noted that his institution has implemented numerous protocols to prevent narcotic abuse in the wake of the opioid crisis.

“We prescribe opioids for no more than six weeks after surgery,” Dr. Sassoon said. “After that, we typically send patients who need longer treatment to a pain specialist, so that we can be confident they are actually on a weaning program.”

He added, “We typically give patients less medication now when they’re leaving the hospital, so they actually have to call us for refills. We want to know if patients are still requiring pain medication two and three weeks after surgery.”

Finally, in an effort to combat potential long-term use, Dr. Sassoon and his orthopedic colleagues try to get patients who have been on narcotics to reduce their dose ahead of surgery.

“I think orthopedic surgeons in general are responding to the opioid epidemic and crisis very well,” Dr. Sassoon concluded. “Because they have to place patients on narcotic pain medication so often, we want to make sure that their dosage is decreasing during the perioperative period. We have really made an effort to be stewards in this regard.”