In America, experienced nurses are retiring at a rapid clip, and there aren’t enough new nursing graduates to replenish the workforce. At the same time, the nation’s population is aging and requires more care.

“It’s really a catch 22 situation,” said Robert Rosseter, spokesman for the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

“There’s tremendous demand from hospitals and clinics to hire more nurses,” he said. “There’s tremendous demand from students who want to enter nursing programs, but schools are tapped out.”

There are currently about three million nurses in the United States. The country will need to produce more than one million new registered nurses by 2022 to fulfill its health care needs, according to the American Nurses Association estimates.

That’s a problem.

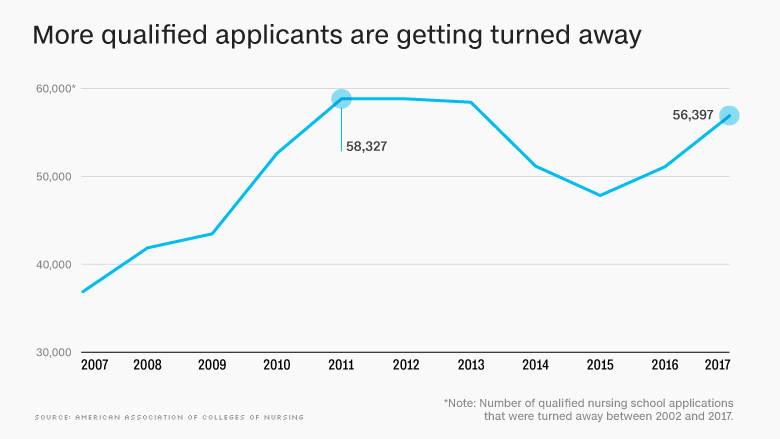

In 2017, nursing schools turned away more than 56,000 qualified applicants from undergraduate nursing programs. Going back a decade, nursing schools have annually rejected around 30,000 applicants who met admissions requirements, according to the American Association of Colleges of Nursing.

“Some of these applicants graduated high school top of their class with a 3.5 GPA or higher,” said Rosseter. “But the competition to get into a nursing school right now is so intense.”

Because of the lack of openings, nursing programs across the board — in community colleges to undergraduate and graduate schools — are rejecting students in droves.

Erica Kay is making her third attempt to get into a nursing program offered in a community college near where she lives in southern California.

Kay, 35, already is a certified surgical technician and a certified medical assistant.

“I’ve been working in health care since I was 21. This is my passion,” she said. “I know I will be a great nurse and I’m studying very hard to get accepted into a program,” she said

She’s taken the standardized admissions test for nursing schools twice and applied to three community colleges. She didn’t get in.

“One school responded in a letter they had 343 applications and only accepted 60 students,” she said. Another school had 60 slots for 262 applications.

“Some programs won’t even consider you if you score less than 80% even if you meet all other criteria,” she said. Kay is retaking the nearly four-hour-long test next month, hoping to better her score.

“It shocks and upsets me that there are so many hurdles to get into nursing school when we have a nursing shortage,” said Kay. “But I am going to keep trying.”

Jane Kirschling, dean of the University of Maryland School of Nursing in Baltimore, said her school admits new students in the undergraduate program twice a year.

“We’re averaging 200 applications each time for 55 slots,” she said. “So we’re turning away one student for every student we accept.”

She said the nursing profession has surged in popularity for a few reasons. “Nursing offers an entry-level living wage with which you can support a family,” said Kirschling.

There’s built-in flexibility and mobility. “You can work three 12-hour shifts and get four days off,” she said. And nurses aren’t locked into a specific location, employer or specialty for the rest of their lives. “There’s tremendous growth opportunity,” said Kirschling.

But Kirschling said increasing school class size to accommodate more students isn’t easy or practical.

For one thing, nursing schools are struggling to hire more qualified teachers. “The annual national faculty vacancy rate in nursing programs is over 7%. That’s pretty high,” said Rosseter. “It’s about two teachers per nursing school or a shortage of 1,565 teachers.”

Better pay for working nurses is luring current and potential nurse educators away from teaching. The average salary of a nurse practitioner is $97,000 compared to an average salary of $78,575 for a nursing school assistant professor, according to the American Association of Nurse Practitioners.

Mott Community College in Flint, Michigan, last year reduced its new admissions from 80 to 64 students accepted twice a year into its two-year associate degree in nursing program.

The move was partly in response to a decision by the Michigan Board of Nursing to shrink the nursing student-to-faculty ratio for clinical training in hospitals and clinics. This was aimed at improving safety and avoiding crowded clinical settings.

“It changed from 10 students for one educator to 8 students. So we had to adjust our class size accordingly,” said Rebecca Myszenski, dean of the division of Health Sciences at Mott Community College.

Kirschling’s school in Baltimore has made similar adjustments. “We used to send eight to 10 nursing students per instructor to hospitals for clinical rotations. Now it’s six students,” she said.

Pediatrics, obstetrics and mental health are the areas where nursing students have the most unmet demand for clinical training,” said Kirschling. “As we try to increase the number of nursing students, these three areas will be bottlenecks for nursing programs.”

Rosseter agrees that class size presents another challenge for nursing schools. “There’s not enough available clinical space to train students,” he said.

Despite the constraints, nursing programs are thinking of ways to accommodate more students.

“We’re expanding our program to new campuses, we’re looking at new models of partnering with hospitals to allow [their] nursing staff to [be able] to teach,” said Tara Hulsey, dean of West Virginia University’s School of Nursing.

For example, Anne Arundel Community College in Arnold, Maryland, offers an accelerated associate nursing program that allows qualified paramedics or veterans to be admitted straight into the second year of the two-year program.

In Flint, Mott Community College has partnered with University of Michigan’s accelerated 16-month undergraduate program designed for veterans with medical experience who want to transition into a nursing career.

“These bridge programs could really help with the [nursing] shortage,” said Myszenski. “You have to address the nursing shortage by thinking out of the box.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.