Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage is an important part of spinal cord ischemia prevention during a thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) procedure. Use of an appropriate guidewire for CSF drain placement is crucial to success, while an inappropriate guidewire may hinder the placement, delay the patient’s surgery, and cause further complications. Guidewire design and composition and its relevance to a procedure is not well understood and may require further evaluation. We present a case in which CSF drain placement was attempted prior to a TEVAR procedure, but the guidewire, included in the drain kit, was unable to be retracted from the catheter.

Disclaimer: Viewers of this material should review the information contained within it with appropriate medical and legal counsel and make their own determinations as to relevance to their particular practice setting and compliance with state and federal laws and regulations. The APSF has used its best efforts to provide accurate information. However, this material is provided only for informational purposes and does not constitute medical or legal advice. This response also should not be construed as representing APSF endorsement or policy (unless otherwise stated), making clinical recommendations, or substituting for the judgment of a physician and consultation with independent legal counsel.

Introduction

Ischemic spinal cord injury is a significant complication of thoracic aortic aneurysm repair, presenting as transient or permanent paresis or paralysis.1 Optimizing spinal cord perfusion pressure via augmentation of mean arterial pressure and reduction of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure can reduce risk of paralysis.2 American and European guidelines recommend placement of a lumbar drain for CSF pressure management for at least 48 hours in patients undergoing open and endovascular thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair for spinal cord protection.2,3

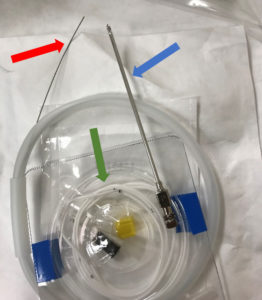

Figure 1 – An opened Integra® HermeticTM Lumbar Catheter Closed Tip kit with straight-ended guidewire (red arrow) exiting the plastic dispenser, spinal needle (blue arrow), and lumbar drain catheter (green arrow) displayed.

Placement of CSF drains usually involves using a guidewire. Guidewires direct placement by giving operators a tactile response corresponding to wire advancement, namely resistance to obstruction.4 A guidewire is composed of a solid core wire made of nitinol or steel, where nitinol is more flexible and better able to return to its original shape.5 Adding a coiled or braided wire around the core adds flexibility and resistance to kinking.5 Guidewire structure can differ in tip shape, flexibility, torque, and steerability.5 Tip shapes are generally angled, straight, or a “J” curve.4 Lubricious wire coatings can reduce friction increase hydrophility.6 CSF drain kits often include the guidewire. Our institution generally uses the Integra® HermeticTM Lumbar Catheter Closed Tip kit (Figure 1). This includes a straight guidewire, specific properties of which are unknown. We present a case in which CSF drain placement was attempted prior to a TEVAR procedure, but the guidewire, included in the drain kit, was unable to be retracted from the catheter. This case highlights the need to evaluate suitability of guidewire type prior to use.

Case

A 70-year-old female presented to our institution for a TEVAR. Lumbar drain placement for CSF drainage was attempted prior to anesthesia induction. An Integra® HermeticTM Lumbar Catheter Closed Tip kit was used. Under sterile conditions, the catheter and guidewire in its dispenser were both flushed with saline. The guidewire was fed through the catheter. With the patient in a sitting position, using anatomical landmarks, after topicalization of skin with lidocaine 1%, a 14-gauge Tuohy spinal needle was inserted into subarachnoid space between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae with observed free flow of CSF. The catheter with guidewire was advanced through the spinal needle to 15 cm without resistance. The Tuohy needle was withdrawn. Holding the catheter in place at the insertion point, resistance was met with retraction of the guidewire. Application of gentle traction followed by increased force did not resolve the issue. The team decided to abort the procedure. The catheter with wire was removed without resistance.

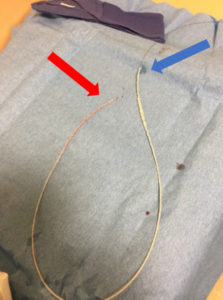

Upon removal, there was lengthwise contraction of the catheter along the wire (Figure 2). No shearing of the catheter was observed. The guidewire tip remained aligned with the catheter’s proximal end. Distally, there was significantly more wire protruding from the catheter (Figure 3). The guidewire was still unable to be withdrawn from the catheter with considerable effort.

Figure 2 – Section of lumbar drain catheter after removal from patient which demonstrates lengthwise contraction.

Figure 3 – Lumbar drain catheter containing guidewire after removal from patient. Guidewire and catheter are aligned at proximal end (red arrow). Catheter is contracted along wire at distal end (blue arrow).

During the procedure, CSF was draining through the large gauge spinal needle, and the patient developed a postdural puncture headache.7 Thus, the team decided to delay drain placement and surgery for three days. Repeat lumbar drain placement was successful under fluoroscopy using the Radifocus® Glidewire® guidewire. The patient was able to undergo an uncomplicated TEVAR with CSF drain in place and was discharged home from the hospital.

Discussion

Few reports of catheter contraction have been published; though there are multiple reports of catheter shearing.8 Risk factors for catheter breakage, including catheter retraction through the needle during placement, faulty guidewire use, or excessive force with catheter removal, may apply to catheter contraction.8 However, the source of our problem is more likely the proximal end of the catheter and guidewire, which failed to separate when the guidewire was pulled, despite judicious flushing of the catheter and wire prior to placement. Attempted retraction of the guidewire caused catheter contraction. We did not report this event to the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience, a US federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) database for medical device reports. However, a 2010 report regarding the same lumbar drain kit, including both wire and catheter, depicts a similar adverse event.9 We hypothesize that an intrinsic fault in the guidewire caused this complication. This is supported by successful placement of the same catheter with a different guidewire, the hydrophilic Radifocus® Glidewire®, a J wire with coaxial wrapping and a floppy tip.10 Currently, we lack evidence-based direction on the optimal wire design for use in placement of a lumbar CSF drain, and further research is needed to prevent similar complications as those seen in this case.

This work is supported by NIH NINDS R21NS113097-01 grant funding.

Arwa Raza in a fourth-year medical student at the Ohio State University College of Medicine in Columbus, OH. She has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Kristine Orion is an associate professor of Vascular Surgery at the Wexner Medical Center at the Ohio State University in Columbus, OH. She has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Hesham Kelani is a post doctorate researcher in the Anesthesiology Department at the Wexner Medical Center at the Ohio State University in Columbus, OH. He has no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Hamdy Awad is an associate professor of Anesthesiology at the Wexner Medical Center at the Ohio State University in Columbus, OH. He has no conflicts of interest.

References

- Awad H, Ramadan ME, El Sayed HF, et al. Spinal cord injury after thoracic endovascular aortic aneurysm repair. Can J Anaesth. 2017;64(12):1218-1235. doi:10.1007/s12630-017-0974-1

- Etz CD, Weigang E, Hartert M, et al. Contemporary spinal cord protection during thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic surgery and endovascular aortic repair: a position paper of the vascular domain of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;47(6):943-957. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezv142

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. 2010;121:e266–369.

- Fornell D. Understanding the Design and Function of Guidewire Technology. Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiology website. October 12, 2016. https://www.dicardiology.com/article/understanding-design-and-function-guidewire-technology Accessed July 13, 2020.

- Fornell D. The Basics of Guide Wire Technology. Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiology website. March 18, 2011. https://www.dicardiology.com/article/basics-guide-wire-technology Accessed July 13, 2020.

- Schummer W. Different mechanical properties in Seldinger guide wires. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2015;31(4):505-510. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.169076

- Rong LQ, Kamel MK, Rahouma M, et al. Cerebrospinal-fluid drain-related complications in patients undergoing open and endovascular repairs of thoracic and thoraco-abdominal aortic pathologies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(5):904-913. doi:10.1016/j.bja.

- Olivar, H., Bramhall, J. S., Rozet, I., et al. Subarachnoid lumbar drains: A case series of fractured catheters and a near miss. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal Canadien D’anesthésie, 2007;54(10), 829-834. doi:10.1007/bf03021711

- MAUDE Adverse Event Report: Integra Neurosciences Hermetic Lumbar Catheter Closed Tip Spinal Drainage. Lot 1102268. October 20, 2010. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfMAUDE/detail.cfm?mdrfoi__id=1917643 Accessed July 14, 2020

- Terumo Interventional Systems. Radifocus® Guidewire M Standard Type. Retrieved September 03, 2020, from https://www.terumo-europe.com/en-emea/products/radifocus®-guidewire-m-standard-type-guide-wire

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.