Intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy has been an essential component of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols, but findings from a recent quality improvement initiative questioned its clinical value and impact.

In the presence of an ERAS pathway that included early ambulation and alimentation, the addition of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy did not reduce complications, readmissions or cost in patients undergoing elective surgery. Although its application was not found to be harmful, when compared with standard care, patients managed with intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy received more IV fluid and had greater variability in fluid administration.

“The value and impact of all ERAS elements must be continuously re-examined,” said Joshua A. Bloomstone, MD, of Valley Anesthesiology and Pain Consultants and clinical professor of anesthesiology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, in Tucson. “We actually no longer advocate the use of goal-directed fluid therapy in the vast majority of patients—only in those in whom hemodynamic compromise is occurring.

“Given how surgery is performed today,” Dr. Bloomstone added, “I believe that goal-directed fluid therapy is much less important than it was in the past.”

As Dr. Bloomstone reported, a number of evidence-based perioperative care elements form the basis of ERAS guidelines, which are thought to improve outcomes and reduce postsurgicalcomplications. Implemented in 2010 as part of a quality improvement initiative across 19 facilities, a small, ERAS pathway that included only two elements was associated with a 28.8% reduction in overall complications (P<0.0001) and a 17.5% reduction in readmissions. An intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy protocol was subsequently added to the pathway in 2013, Dr. Bloomstone said, with the hypothesis that outcomes would be further enhanced while reducing costs.

“We began our study with an enormous education campaign and used only our facilities that had electronic anesthesia recording systems, so we could capture all of the data and see whether [fluid optimization] was delivered or not,” Dr. Bloomstone said. “We included only those cases that had been included in the literature, and we automated the entire process—from pre-op to post-op—to enhance compliance with the protocol.”

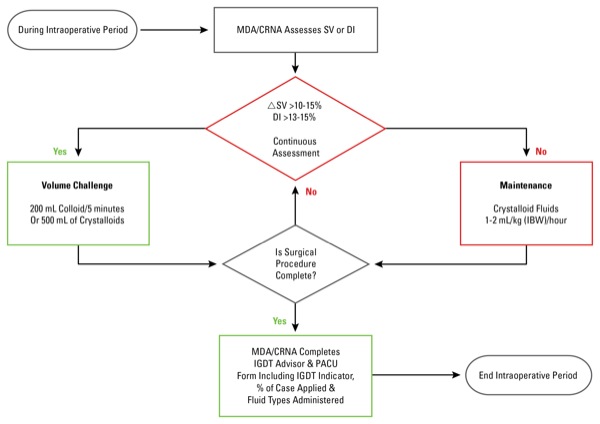

Dr. Bloomstone and his colleagues applied intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy to 528 surgical patients undergoing elective colon and small-bowel surgery, hysterectomy, hip arthroplasty and repair of lower extremity long bone fractures (Figure). The analysis included 528 patients with matched “control” patients, who underwent one of the specified surgical procedures but did not receive intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy during the specified time frame.

No Reduction in Complications, Readmissions or Cost

As Dr. Bloomstone reported at the International Anesthesia Research Society 2017 annual meeting (abstract 2118), the application of intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy did not reduce complications (P=0.6456), readmissions (P=0.7408) or cost per case (P=0.1241). When there was a difference in length of stay, however, it was statistically longer for patients receiving the intervention, which was driven by low ASA physical status score, the authors noted.

In addition, Dr. Bloomstone said, analysis showed that patients receiving the intervention received more overall fluid, which has been demonstrated in prior studies. Variability in fluid administration also was greater when clinicians used a standardized fluid protocol based on physiologic parameters versus standard of care. Of note, Dr. Bloomstone added, no increase in complications was observed in patients receiving goal-directed fluid therapy.

“It’s important to recognize that all trials like this really reflect the care of the comparator group necessarily more so than the intervention,” Dr. Bloomstone observed. “This does not mean that intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy outside of an enhanced recovery protocol will not enhance care—it may.”

Goal-Directed Approach Still Prudent

The widely different surgical procedures included in the cohort is problematic, as these procedures have different lengths of stay. For example, a hysterectomy may be done in an ambulatory setting at many hospitals, whereas small-bowel surgery may require a longer stay in the hospital. It is unclear what levels of matching were done.

In addition, more procedures are minimally invasive, either laparoscopic or robotic, and the need for fluid resuscitation is significantly less than with traditional open laparotomy. This may minimize the effect of goal-directed fluid therapy (GDFT).

A recent prospective clinical trial by Pearse et al (JAMA 2014;311:2181-2190) showed a 16% risk reduction in surgical complications (relative risk, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.71-1.01; P=0.07) in the group where GDFT was used versus control in the presence of an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. The difference missed statistical significance due to inadequate sample size. The same group is undertaking a larger international multicenter clinical trial, which addresses the role of GDFT or hemodynamic optimization using an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. The results from these trials will further guide us on its role.

Given that there is no difference in costs between the two groups, it may be prudent to adopt a goal-directed approach for intraoperative fluid administration, especially in high-risk patients undergoing major surgical procedures.

According to the researchers, the combination of minimally invasive surgery, avoidance of dehydrating bowel preparations and adherence to the ASA’s NPO (nothing by mouth) guidelines for clear liquid consumption all contribute to a far more balanced perioperative volume status than in years past.

“Intraoperative goal-directed fluid therapy may be less impactful on elective surgical outcomes than it once was in our surgical population,” Dr. Bloomstone concluded.

An attendee of the presentation noted that divergence from previous studies may be attributable to “incorrect” expected values, as results were reported as observed-to-expected ratios.

“That’s entirely possible,” Dr. Bloomstone said. “All of our surgical data is yielded to Premier, which calculated expected values with a proprietary risk adjustment methodology, using historical data within the database.”

What Are the Implications?

The moderator of the session, John Sear, MBBS, PhD, professor of anesthesia at the University of Oxford, in England, inquired about the study’s possible implications.

“If your data hold up to scrutiny, how can you show that goal-directed fluid therapy is an unnecessary venture?” Dr. Sear asked.

“Today, goal-directed fluid therapy is simply administered by anesthesiologists the moment a patient enters into an operating room, but I believe there really needs to be a reason to administer a physiologic protocol,” Dr. Bloomstone said. “I think that perioperative medicine has changed since the time that the bulk of the goal-directed fluid therapy data was collected. Two criteria should be met prior to the administration of intraoperative fluids: First, the patient must require augmentation of their perfusion. Second, the patient must be fluid responsive. The intraoperative administration of fluids based solely on fluid responsiveness is neither physiologically sound nor should it enhance surgical outcomes.”

“That’s why I offer a big caveat with using historical data as your control group,” Dr. Sear said. “Much has changed. I think the challenge moving forward is to find a contemporary control group.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.