Author: Lynne Peeples

Anesthesiology News

Ten years since the first report of Candida auris—found in a patient with an ear infection in Japan—the highly drug-resistant fungus has taken a foothold in many parts of the world, including the United States. Infectious disease experts are responding with pleas for greater efforts to control and contain the spreading public health threat.

“It’s really hard to kill. I think it’s caught all of us a little off guard,” said Tom Chiller, MD, the chief of the Mycotic Diseases Branch at the CDC.

Historically, there were only a handful of Candida fungi that caused human disease. For drug resistance to develop, people needed to use the antifungals for long periods, such as would occur in immunocompromised patients with HIV who may be infected repeatedly, noted Jeffrey Rybak, PharmD, PhD, an infectious disease pharmacist and mycologist at the University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy in Memphis. Over the last three decades, less common species began to emerge with higher baseline rates of resistance, such as C. glabrata and C. tropicalis. Still, multidrug resistance was relatively rare.

Then, in 2009, along came C. auris, and everything changed.

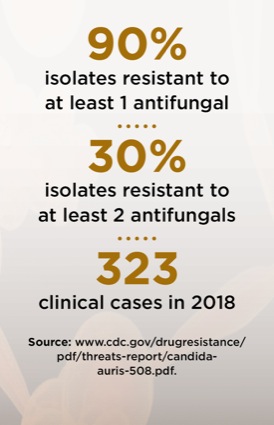

The CDC has confirmed approximately 800 domestic cases of C. auris. Much like carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and other drug-resistant bacteria, the yeast is readily transmitted in health care settings and has often been found to be either drug resistant at the outset of infection or has acquired resistance.

From C. auris Colonization To Infection

Nearly all of those approximately 800 confirmed cases—likely an underestimate given that many cases may go unidentified—have been in three states: Illinois, New Jersey and New York. The CDC has also identified more than 1,600 cases of colonization.

A unique characteristic of C. auris is its ability to colonize the skin for prolonged periods, making it much more easily spread. Once colonized with the organism, a patient today is considered always colonized, Dr. Chiller said. Between 5% and 10% of colonization cases become infections.

Of particular concern are long-term care facilities, where the fungus can spread and persist on surfaces such as bedrails, floors or shared equipment for weeks, even months. Effective sterilization and handwashing are critical to keep the organism at bay. “If it goes unidentified, it can establish a foothold in that institution and then begin this cascading effect of colonizing and later infecting more and more patients,” Dr. Rybak said.

At that point, eradication is difficult. Quaternary ammonium compounds are among common agents that frequently fail against the species. David W. Denning, MB BS, a professor of infectious diseases in global health at the University of Manchester, in England, co-authored a paper that outlined infection prevention and control measures (Int J Antimicrob Agents 2019;54[4]:400-406). The authors recommended at least twice-daily cleaning of all high-touch surfaces with cleaners such as sodium hypochlorite, peracetic acid and vaporized hydrogen peroxide—while being careful of the products’ toxicities.

Improved Identification and Control

Among the factors that make C. auris “challenging to identify,” Dr. Denning said, is that it requires skin swabs to identify carriers “as this Candida likes salty parts of the body, not the gut like most other Candida species.”

What’s more, most hospitals are not well equipped to distinguish different Candida species from a skin swab or clinical isolates. “Even if they sent a culture to a regional hospital, the most common readily available clinical platforms were not designed to identify this organism,” said Dr. Rybak, noting that even the updated versions of these platforms are only correct about half the time (J Clin Microbiol 2019 Aug 14. [Epub ahead of print]).

A less common platform known as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry is nearly 100% accurate in detecting C. auris. So far, few hospitals are able to purchase the platform due to its high cost (J Clin Microbiol 2018;56[4]:e01700-17).

Meanwhile, the CDC has rolled out another accurate tool for screening patients for C. auris in its seven antimicrobial-resistant labs: Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR platform. The labs, however, are not necessarily meant to be used for clinical care.

Drs. Chiller and Rybak highlighted the need for more robust screening protocols and the identification of patients who have been through care facilities or parts of the world where the species is prevalent. One strategy may be to put these at-risk patients in contact isolation until confirmation is obtained. “If tests come back negative, then you can take them out,” Dr. Chiller said.

“We have to be vigilant and aggressive if we want to control and contain this organism,” he added. “We don’t want the organism to set up shop in lots of our hospitals.”

Trouble With Treatments

C. auris is far more resistant to antifungals than other species of Candida. The yeast is resistant to fluconazole 90% of the time. Fluconazole represents about 80% of all antifungal use in the United States, partly due to its low price and ease of IV or oral administration.

About 40% of C. auris infections are resistant to amphotericin B, which is only available intravenously, and carries a high price and high adverse event profile. It is particularly nephrotoxic (Ann Intern Med 2019 Jul 30. [Epub ahead of print]). Still, the drug has the broadest spectrum of activity against fungal infections and is commonly relied upon as the last line of defense.

The last major class of antifungals, echinocandins, is recommended as first-line treatment for C. auris infections due to a relatively low resistance rate of about 2%. However, three cases were reported in 2019 in which the organism was susceptible to the drugs when initiated but then developed resistance during treatment, according to the CDC.

If a patient does not appear to be improving on echinocandins, Dr. Rybak recommended obtaining a confirmatory culture and considering the addition of a secondary agent. However, the use of multiple antifungals is not routinely recommended, he said.

Dr. Rybak emphasized that C. auris need not be a cause for panic. “The better we are at looking out for it,” he said, “the better we can make sure we are appropriately identifying and treating it, and the less of a problem it will become.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.