SUMMARY: GLP-1 receptor agonists are an increasingly popular class of medications for weight loss and diabetes management. An important mechanism for these medications is direct gastric stimulation of GLP-1 receptors leading to delayed gastric emptying and potential for retained gastric contents in patients presenting for anesthesia. This article explores the challenges these medications may pose for the anesthesia professional.

INTRODUCTION

Glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1) receptor agonists are an emerging and increasingly popular class of medications used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus and, more recently, obesity. Since the expansion of approved uses to include weight loss, these medications have become increasingly popular. One mechanism of action of GLP-1 agonists is delayed gastric emptying.1 We describe two cases of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists that were found to have high volumes of complex gastric contents despite appropriate fasting per American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) practice guidelines for preoperative fasting.2 With the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists becoming increasingly more common, anesthesia professionals need to be aware of these medications and the potential risks they pose to patients receiving anesthesia.

CASE 1

A 60-year-old female presented for magnetic resonance imaging with sedation for claustrophobia. She had a history of hypertension and was overweight (body mass index [BMI] 28 kg/m2). The month prior, she started semaglutide (Ozempic, Novo Nordisk, Plainsboro, NJ) for weight loss (last dose 7 days prior to presentation). Despite fasting from solid food for more than 18 hours prior to evaluation, she described feeling “full.” A point-of-care gastric ultrasound was performed, which revealed solid gastric contents. The decision was made to cancel her imaging for fear of high risk of aspiration during the delivery of anesthesia.

CASE 2

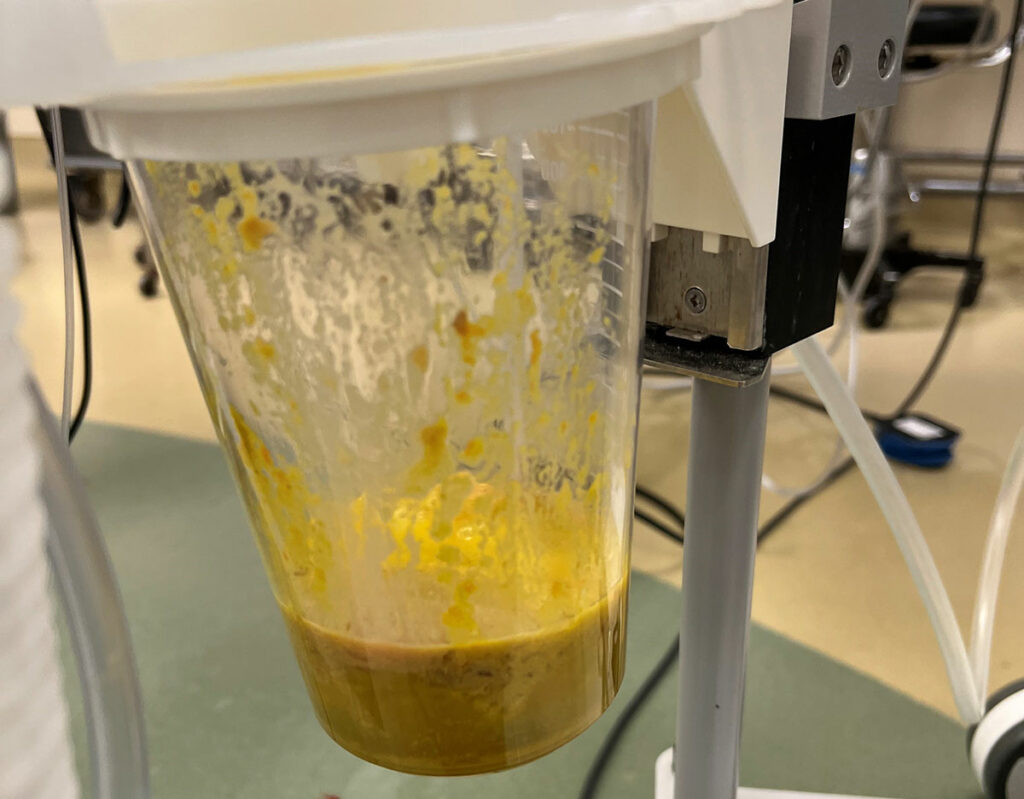

Figure 1 : Depicts gastric contents in a patient on a GLP-1 agonist, who appropriately adhered to ASA fasting guidelines.

A 50-year-old female with past medical history of class 2 obesity (BMI 37.7 kg/m2), type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was scheduled to undergo a robotic-assisted hysterectomy for endometrial hyperplasia. Of note, she previously had gastroesophageal reflux disease, but these symptoms had resolved since she started tirzepatide (Mounjaro, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) 12.5 mg/0.5 mL pen injector injection (last dose 2 days before surgery). Her other medications included: metformin, hydrochlorothiazide, pregabalin, oxycodone, 5 mg as needed (intermittent use with last dose the day prior to surgery), and sertraline. She had been fasting since the night before surgery.

Anesthesia proceeded with an uneventful induction of general anesthesia and intubation. After intubation, an orogastric tube was placed and gastric contents (Figure 1) were suctioned.

The case was uncomplicated from a surgical perspective. At case completion, the patient was transferred to the transport cart and sat up in anticipation of emergence. Shortly before she was ready for extubation, she developed large volume emesis of particulate matter that was consistent with what she reported eating several days prior to surgery (Figure 2). Fortunately, the endotracheal tube was still in place and her airway remained protected. Once emesis was cleared, she was uneventfully extubated. She was closely observed in the PACU and did not have evidence to suggest gastro-pulmonary aspiration and was therefore discharged home later that day.

Figure 2 : Depicts large volume emesis of particulate matter in a patient on a GLP-1 agonist that was consistent with what the patient reported eating several days prior to surgery.

DISCUSSION

GLP-1 receptor agonists are an increasingly popular class of medications being prescribed to patients. These medications have been described as a “breakthrough” for weight loss. The GLP-1 receptor is expressed in a diverse range of organ systems including gastrointestinal (GI) tract, pancreas, heart, liver, and brain. Stimulation of this receptor leads to weight loss, improved glycemic control in diabetic patients, and improved cardiac and renal outcomes. The primary mechanism of action is related to both activation of vagal afferent nerves innervating the stomach as well as direct binding to GLP-1 receptors on gastric mucosal cells leading to delayed gastric emptying.1 For diabetics, weight loss combined with stimulation of insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells results in optimized hemoglobin A1c.3 Improvement in major acute cardiac events is likely related to both overall risk factor reduction (e.g., decreased glycated hemoglobin level, blood pressure control, decreased body mass index, decreased low density lipoprotein cholesterol level, improved glomerular filtration rate, and the decreased albumin-to-creatinine ratio) as well as via direct stimulation of GLP-1 receptors on myocardium leading to better endothelial function and microvascular perfusion.4,5 GI side effects like nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea are common, but symptoms may decrease with continued use.6 Acute pancreatitis as well as gallbladder and biliary disease, such as cholecystitis, have also been described. Although rare, anaphylactic and angioedema reactions have been described.7

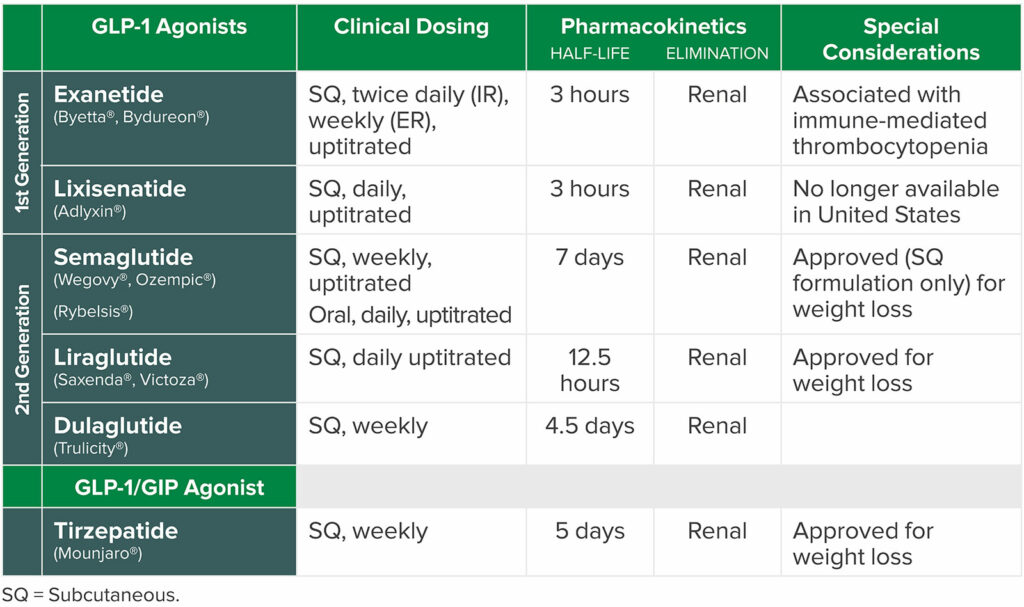

Despite the benefits of the class of medications on obese and diabetic patients, there are potential anesthetic risks. GLP-1 receptor agonists have a known mechanism of action of slowed gastric emptying.8 The medications may lead to high volumes of complex gastric contents despite appropriate fasting per ASA practice guidelines for preoperative fasting. Both patients presented in this case series were taking a GLP-1 receptor agonist (Table 1) to treat diabetes and assist with weight loss. And, although pulmonary aspiration is a rare complication in patients undergoing anesthetic care, it is devastating. In addition, it is among the top three adverse events related to airway management in the ASA closed claims project.9 The most common etiology of aspiration is related to passive or active regurgitation of gastric contents.10,11 For this reason, recognition of patient populations at elevated risk for increased gastric volume is key to delivering a safe anesthetic (Table 2).

Table 1: Common GLP 1 Agonists.16,17

Table 2: Risk Factors for Aspiration

Esophageal Pathology

|

High risk for ileus/bowel dysmotility

|

Intra-abdominal Obstruction

|

Emergency Case |

| Known, suspected or induced gastroparesis (longstanding diabetes, neuromuscular disorders, medications-e.g., GLP-1 agonist) | Case with prolonged duration or complexity |

| Pregnancy | Active GI Bleed |

- Asai T. Editorial II: Who is at increased risk of pulmonary aspiration? Br J Anaesth. Oct 2004;93(4):497-500. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh234

- Robinson M, Davidson, A. Aspiration under anaesthesia: risk assessment and decision-making. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain 2014;14:171-175.

- Beam W. Aspiration Risk Factors. Mayo Clinic Surgical and Procedural Emergency Checklist: Mayo Clinc; 2023.

- Bohman JK, Jacob AK, Nelsen KA, et al. Incidence of Gastric-to-Pulmonary Aspiration in Patients Undergoing Elective Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Jul 2018;16(7):1163-1164. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.11.024

Although it was avoided in these cases, the risk for pulmonary aspiration in sedated or anesthetized patients with unprotected airways is concerning. In the first case, close attention to the patient’s history and symptoms, combined with assessment with gastric ultrasound, led to case cancellation and avoidance of a high-risk situation for the patient. In the second case, the patient was noted to have a high volume of complex intragastric contents with orogastric tube placement and emesis of solid gastric contents at the time of emergence consisting of food from 2–3 days before surgery.

It is unclear if the GLP-1 receptor agonist was the direct cause of the high volume of remaining gastric contents as the patient also had long-standing diabetes and was using opioids, both associated with gastroparesis.12,13 As evidence of our concern about patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists, we identified a recent case report that described a patient taking semaglutide who experienced an aspiration event with food remains during induction of anesthesia despite having fasted for 18 hours.14 Furthermore, we found several retrospective reviews of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists undergoing endoscopy that showed an increased risk of retained gastric contents in patients on these medications.15,16

The ASA’s Task Force on Preoperative Fasting recently released a consensus-based guidance on preoperative management of patients on GLP-1 receptor agonists (Figure 3).17 For elective procedures, the expert group’s recommendation is to withhold daily dosed GLP-1 receptor agonists the day of the procedure and weekly-dosed formulations a week prior. On the day of the procedure, the recommendation is to ask specifically about GI symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal distension, and consider delaying elective procedures in patients who are symptomatic. If patients are asymptomatic from a GI standpoint and medications were held per guidance, their recommendation is to proceed with the procedure. In patients without GI symptoms, but who have not held the medication as advised, the task force recommends proceeding with “full stomach” precautions with consideration for evaluating gastric volume by ultrasound to aid in decision-making. This group noted there is no evidence to suggest optimal duration of fasting.17 Other professional organizations such as the Society of Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement have also put forward consensus recommendations to hold GLP-1 receptor agonists on the day of surgery unless there is heightened concern for postoperative gut dysfunction.18 Given the long half-life of most medications within this class, stopping medications for at least 5 half-lives before surgery to allow normalization of gastric function is not feasible. Further, given the potential cardiovascular benefits and negligible risk for hypoglycemia, there is interest in continuing this class of medications without perioperative interruption.19

Figure 3: American Society of Anesthesiologists Consensus-Based Guidance on Preoperative GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Management*

| Assessment: Given concerns regarding reports of delayed gastric emptying related to GLP-1 receptor agonists, the ASA Task Force on Preoperative Fasting released guidance regarding preoperative management of these medications.For patients scheduled for elective procedures consider the following:Day(s) Prior to the Procedure:

Day of the Procedure:

*Excerpted from American Society of Anesthesiologists Consensus-Based Guidance on Preoperative Management of Patients (Adults and Children) on Glucagon-like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Receptor Agonists. https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2023/06/american-society-of-anesthesiologists-consensus-based-guidance-on-preoperative. Updated June 29, 2023. American Society of Anesthesiologists. |

At this point, the optimal approach to these patients still needs to be refined and hopefully additional studies will help guide our decision-making. A systematic approach to assessing risk in this patient population with a careful history of medication use, symptoms, and review of comorbidities is important. It may be prudent to re-evaluate traditional fasting guidelines in these patients. The use of gastric ultrasound to define gastric contents prior to anesthesia can be considered in patients presenting for anesthesia on these medications, when available.20-22

In the setting of uncertainty regarding gastric contents, rapid sequence induction of anesthesia and gastric decompression prior to emergence could be considered. It should also be recognized that the risk for emesis and aspiration during emergence is also a real concern even with gastric decompression if the patient has residual solid gastric contents.

CONCLUSION

We present two cases of patients on GLP-1 receptor agonists with delayed gastric emptying despite appropriate preoperative fasting. We acknowledge it is difficult to ascertain the direct cause of the delayed gastric emptying in these patients as there were numerous risk factors. Nevertheless, with the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists becoming increasingly common, anesthesia professionals need to be aware of these medications and the potential risks they pose to patients receiving anesthesia. Further studies investigating the safety of these agents as it relates to the management surrounding the peri-anesthetic period are needed.

REFERENCES

- Prillaman M. “Breakthrough” obesity drugs are effective but raise questions. Scientific American. 2023 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/breakthrough-obesity-drugs-are-effective-but-raise-questions/ Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Joshi GP, Abdelmalak BB, Weigel WA, et al. 2023 American Society of Anesthesiologists practice guidelines for preoperative fasting: carbohydrate-containing clear liquids with or without protein, chewing gum, and pediatric fasting duration—a modular update of the 2017 American Society of Anesthesiologists practice guidelines for preoperative fasting. Anesthesiology. 2023;138:132–151. PMID: 36629465.

- Holst JJ, Orskov C. The incretin approach for diabetes treatment: modulation of islet hormone release by GLP-1 agonism. Diabetes. 2004;53:S197–204. PMID: 15561911.

- Gerstein HC, Sattar N, Rosenstock J, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with efpeglenatide in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:896–907. PMID: 34215025.

- Heuvelman VD, Van Raalte DH, Smits MM. Cardiovascular effects of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: from mechanistic studies in humans to clinical outcomes. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:916–930. PMID: 31825468.

- Trujillo J. Safety and tolerability of once-weekly GLP-1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45:43–60. PMID: 32910487.

- Ornelas C, Caiado J, Lopes A, et al. Anaphylaxis to long-acting release exenatide. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2018;28:332–334. PMID: 30350785.

- Urva S, Coskun T, Loghin C, et al. The novel dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist tirzepatide transiently delays gastric emptying similarly to selective long-acting GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:1886–1891. PMID: 32519795.

- Bailie R, Posner KL. New trends in adverse respiratory events from ASA Closed Claims Project. ASA Newsletter. 2011;75:28–29. https://pubs.asahq.org/monitor/article-abstract/75/2/28/2553/New-Trends-in-Adverse-Respiratory-Events-From-ASA?redirectedFrom=fulltext Accessed March 9, 2023.

- Mendelson CL. The aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs during obstetric anesthesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1946;52:191–205. PMID: 20993766.

- Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:56–62. PMID: 8424572.

- Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1225–1233. PMID: 19249393.

- Camilleri M. Gastroparesis: etiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. UpToDate. 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/gastroparesis-etiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis Accessed July 5, 2023.

- Klein SR, Hobai IA. Semaglutide, delayed gastric emptying, and intraoperative pulmonary aspiration: a case report (Semaglutide, vidange gastrigue retardee et aspiration pulmonaire peroperatoire: une presentation de case). Can J Anaesth. 2023; Mar 28. PMID: 36977934. Online ahead of print.

- Kobori T, Onishi Y, Yoshida Y, et al. Association of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment with gastric residue in an esophagogastroduodenoscopy. J Diabetes Investig. 2023:14:767–773. PMID: 36919944.

- Silveira SQ, da Silva LM, de Campos Vieira Abib A, et al. Relationship between perioperative semaglutide use and residual gastric content: a retrospective analysis of patients undergoing elective upper endoscopy. J Clin Anesth. 2023;87:111091. PMID: 36870274.

- Girish PJ, Abdelmalak BB, Weigal WA, et al. American Society of Anesthesiologists consensus-based guidance on preoperative management of patients (adults and children) on glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists. asahq.org. Updated June 29, 2023. https://www.asahq.org/about-asa/newsroom/news-releases/2023/06/american-society-of-anesthesiologists-consensus-based-guidance-on-preoperative Accessed July 5, 2023.

- Pfeifer KJ, Selzer A, Mendez CE, et al. Preoperative management of endocrine, hormonal, and urologic medications: Society for Perioperative Assessment and Quality Improvement (SPAQI) consensus statement. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96:1655–1669. PMID: 33714600.

- Hulst AH, Polderman JAW, Siegelaar SE, et al. Preoperative considerations of new long-acting glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in diabetes mellitus. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:567–571. PMID: 33341227.

- Kruisselbrink R, Gharapetian A, Chaparro LE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care gastric ultrasound. Anesth Analg. 2019;128:89–95. PMID: 29624530.

- Cubillos J, Tse C, Chan VW, Perlas A. Bedside ultrasound assessment of gastric content: an observational study. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59:416–423. PMID: 22215523.

- Schwisow S, Falyar C, Silva S, Muckler VC. A protocol implementation to determine aspiration risk in patients with multiple risk factors for gastroparesis. J Perioper Pract. 2022;32:172–177.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.