Anesthesiology News

Introduction

The following case report details the discovery of upper respiratory tract sarcoid granulomas during direct laryngoscopy in a 69-year-old man undergoing spinal surgery. Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT) is a rare subset of sarcoidosis, and although it is often asymptomatic, it may present challenges for the anesthesiologist during airway manipulation. It is essential to be aware of this manifestation and have a contingency plan if conventional laryngoscopy and intubation are not possible.

Sarcoidosis is a rare multisystem disease classically associated with respiratory, cardiac and central nervous system sequelae.1 One of the more uncommon and infrequently discussed presentations is laryngeal sarcoidosis, which manifests as granulomas in the epiglottis, arytenoids, aryepiglottic folds and/or false vocal cords.2 Although often asymptomatic, these granulomas may be a potential cause of a difficult airway for an unsuspecting anesthesiologist. The following case describes the incidental discovery of upper respiratory tract sarcoid granulomas during direct laryngoscopy. Written consent was obtained from the patient for case publication.

Case Description

A 69-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, hypertension and sarcoidosis presented to our institution for a staged spinal surgery. The patient had a previous L1-L5 posterior instrumented spinal fusion but was experiencing intensifying back pain with worsening junctional kyphosis. After failing conservative management, the decision was made to proceed with surgical revision.

On examination, the patient was determined to have a favorable airway, being classified as Mallampati I with normal mouth opening and no restriction of cervical range of motion. On the basis of this information, general endotracheal anesthesia in the prone position was planned, with maintenance to be provided by total IV anesthesia to facilitate neuromonitoring.

The patient was brought to the OR and standard monitors were applied. After preoxygenation, induction was accomplished with 2 mg of midazolam, 100 mcg of fentanyl, 140 mg of propofol and 120 mg of succinylcholine. Direct laryngoscopy was then attempted with a Macintosh 3 blade; however, visualization of the glottic opening was completely obstructed by a soft tissue mass arising from the right hypopharynx.

The laryngoscope was then withdrawn and reinserted in a more midline manner, with additional anterior force applied. The obstructing mass was sufficiently displaced, and a grade 2a Cormack-Lehane view of the glottis was achieved. A 7.5-cm cuffed endotracheal tube was maneuvered around the soft tissue mass and the trachea intubated. The surgery proceeded without incident, and the patient was extubated at the conclusion of the case. He was transported to the PACU in stable condition and did not experience any adverse respiratory sequelae. As per institutional procedure, a patient status modifier and note were entered into the electronic health record, and a wristband was applied to alert providers of a potentially difficult airway.

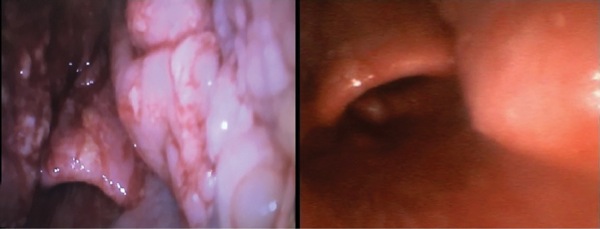

After an uneventful course in the neurointensive care unit, the patient returned to the OR two days later as planned for the second stage of his surgery. There was no change in his condition since the original operation. He was induced with the same regimen of midazolam, fentanyl, propofol and succinylcholine. To better visualize the soft tissue mass in the hypopharynx and avoid potential difficulty, video laryngoscopy using a GlideScope (Verathon) was selected. A size 3 blade was inserted midline and soft tissue masses in the hypopharynx were again visualized (Figure). Advancement of the blade displaced the masses laterally, and an unimpeded view of the vocal cords was obtained. The patient was then intubated with a 7.5-cm cuffed endotracheal tube.

Surgery proceeded as expected, but the patient was left intubated at the conclusion of the case due to hemodynamic instability unrelated to his sarcoidosis. His postoperative course was further complicated by suspected toxic shock secondary to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. After treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics, the patient was successfully extubated and transferred to an acute rehab facility several weeks later.

Discussion

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease with an incidence of only 30 per 100,000.1,3 It is most common in the 20- to 40-year age demographic and preponderantly found in the black population.1 The disease is characterized by diffuse granuloma formation, likely in response to environmental triggers.1 The lung is the most frequently affected organ.3 Respiratory manifestations include cough, dyspnea, chest discomfort and wheezing. Untreated sarcoidosis can lead to pulmonary hypertension from fibrosis or granulomatous infiltration.1

Other affected systems include the neurologic system, manifesting as cranial nerve palsies, headache and seizures; cardiac system, manifesting as dysrhythmias and heart block; and integumentary system, leading to the formation of macules, papules and plaques.1

Laryngeal sarcoidosis is an uncommon and infrequently discussed manifestation, but one that may have significant clinical implications for the anesthesiologist. Laryngeal sarcoidosis was first documented in the 1940s, approximately 70 years after sarcoidosis was first described.4,5 The lag time is presumably due to the rarity of the condition; the exact incidence is unknown but estimated to be present in only 1% to 5% of patients with sarcoidosis.6,7 This may be an underrepresentation, however, as symptoms of laryngeal sarcoidosis may be falsely attributed to pulmonary sarcoidosis, thus preventing the workup and subsequent diagnosis of laryngeal sarcoidosis.8,9

Laryngeal sarcoidosis is characterized by nodule formation in the supraglottic area resulting from granulomatous infiltration.7 The epiglottis is the most common structure affected and has a pathognomonic appearance—thickened, pale and edematous—which is often described as “turban shaped.”9 Arytenoids, aryepiglottic folds and false vocal folds also may be affected, while true vocal cords are typically spared.7,10

Presenting symptoms of laryngeal sarcoidosis include hoarseness, dyspnea, dysphagia, cough and obstructive sleep apnea. Alternatively, it may be asymptomatic.10 Initial treatment is with oral prednisone therapy; if that fails, obstructing lesions may be treated with surgery, carbon dioxide laser ablation or external beam radiation.7

Together with sinonasal sarcoidosis, laryngeal sarcoidosis comprises the classification known as SURT. Sinonasal sarcoidosis often occurs concurrently with laryngeal sarcoidosis, and may present with symptoms such as nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, anosmia and epistaxis.2,10 Lupus pernio, a condition consisting of purple-colored indurated lesions on the face, is frequently associated with SURT; the incidence was found to be as high as 54% in one study of 818 patients.10,11 Thus, the presence of facial lesions on a patient with known sarcoidosis may warrant further workup for SURT.

Laryngeal sarcoidosis can pose challenges with airway management. Granulomas of the supraglottic area may impede the glottic opening during laryngoscopy. Even if the glottis is visualized, passage of an endotracheal tube may require extra manipulation and/or downsizing. In some circumstances, intubation may not be possible. The patient in this case study was fortunate enough to be asymptomatic from his disease and successfully intubated with a slightly modified laryngoscopy technique. However, case reports exist of patients presenting with symptomatic laryngeal sarcoidosis requiring more drastic interventions.

Ryu et al detailed a 37-year-old black woman who presented to the emergency department with acute dyspnea and stridor.12 She was not on steroid therapy for her sarcoidosis; she opted for homeopathic therapies. Bedside laryngoscopy revealed an obstructed airway with the epiglottis retroflexed over the glottis and substantial edema of the arytenoids. She was given high-dose dexamethasone therapy and intubated via direct laryngoscopy in the OR. A tracheostomy was performed thereafter, and she was discharged home several days later on prednisone therapy.12

When conducting a preoperative history and physical of a patient with sarcoidosis, it is prudent to inquire about symptoms that may suggest the presence of SURT, including snoring, dyspnea, dysphagia, cough, epistaxis and anosmia. Purplish indurated lesions on the face, characteristic of lupus pernio, should heighten the anesthesiologist’s index of suspicion for SURT. The absence of symptoms or physical findings does not necessarily rule out SURT, as demonstrated by the patient profiled above.

Additionally, the standard preoperative airway assessment, including Mallampati classification, may not reveal the presence of such lesions due to their deeper location. Therefore, when managing a patient with sarcoidosis, surgical records should be reviewed, if available.

A careful and well-thought-out airway management plan should be devised. Alternate methods of airway intervention, including video laryngoscopy, fiber-optic bronchoscopy or a surgical airway kit, also should be readily accessible. Provider awareness of SURT and its manifestations can prevent a minor inconvenience from turning into a potentially catastrophic event.

References

- Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2153-2165.

- Duchemann B, LavolÉ A, Naccache JM, et al. Laryngeal sarcoidosis: a case-control study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(3):227-234.

- Rosenberg AD. Sarcoidosis. In: Fleisher LA, Roizen MF, Roizen JD, eds. Essence of Anesthesia Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2018:366-366.

- Poe DL. Sarcoidosis of the larynx. Arch Otolaryngol. 1940;32(2):315-320.

- James DG, Sharma OP. From Hutchinson to now: a historical glimpse. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8(5):416-423.

- Wills MH, Harris MM. An unusual airway complication with sarcoidosis. Anesthesiology. 1987;66(4):554-555.

- Polychronopoulos VS, Prakash UBS. Airway involvement in sarcoidosis. Chest. 2009;136(5):1371-1380.

- Neel HB, McDonald TJ. Laryngeal sarcoidosis: report of 13 patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91(4 pt 1):359-362.

- Sims HS, Thakkar KH. Airway involvement and obstruction from granulomas in African-American patients with sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2007;101(11):2279-2283.

- Edriss H, Kelley JS, Demke J, et al. Sinonasal and laryngeal sarcoidosis—an uncommon presentation and management challenge. Am J Med Sci. 2019;357(2):93-102.

- Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein AS, et al. Thalidomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Chest. 2002;122(1):227-232.

- Ryu C, Herzog EL, Pan H, et al. Upper airway obstruction requiring emergent tracheostomy secondary to laryngeal sarcoidosis: a case report. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:157-159.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.