The American Civil War is almost as much a story of disease as it is one of armies and battles. The numbers are staggering. Current scholarship puts the total deaths in the war at more than 750,000. Over twice as many soldiers died from disease as from battlefield injuries. Huge numbers of troops suffered diseases but survived.

At the start of the war, both sides faced a shortage of a very important medicine: quinine. Each side had to deal with that shortage in a very different way.

Morbidity and Mortality

We know much about the Union army’s medical history due to the publication between 1870 and 1888 of the six volumes of “The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 1861-65” (MSHWR). This massive work contains detailed tabular summaries and case reports from individual surgeons based on their wartime records.

No such equivalent is available for the Confederacy, because records were burned as the government retreated from Richmond, Va., at the end of the war. Some of the South’s medical history has been developed from post-war memoirs and articles by Confederate physicians and nurses. The experience of disease among Confederate troops seems to have been similar to those of the Union’s.

Dysentery and other forms of diarrhea were the most common problems. The Union army suffered a total of 1.6 million cases. Just from July 1862 through June 1863, there were 522,000 cases of dysentery, with 10,554 deaths. These ailments were so widespread that an entire volume of the MSHWR is devoted to them.

Responsible for much of this morbidity were camp conditions and soldier diet. The troops rarely ate fresh vegetables, so scurvy was a frequent problem. Both armies subsisted primarily on pork, beans, coffee and hardtack (6 parts flour, 1 part water). The Confederates had cornbread instead of hardtack. For the Union army, Congress passed a law allowing “desiccated” vegetables. This creation consisted of canned mixed vegetables compressed into bricks 1 inch thick and a foot long. This “food” was used to make a soup that required one to three hours cooking time and tasted terrible. Troops on both sides foraged locally for food whenever possible.

About one-fourth of diseases reported among white Union troops were “malarial.” U.S. Army Assistant Surgeon Joseph Woodward, MD, published “Outlines of the Chief Camp Diseases of the United States Armies” in 1863; much of the book is concerned with fevers. According to the MSHWR, from May 1861 until June 1866 there were 12,199 deaths from malarial fevers among white Union troops. During a shorter period—July 1, 1863, through June 30, 1866—about 3,224 black troops died. In total, there were 1,372,355 cases of these fevers among black and white troops. This aggregate case total did not include soldiers who appeared for morning sick call but were not sent to a hospital or relieved of duty.

Southerners hoped the invading Union troops would be impeded by the climate of their region and malaria and other diseases that were widespread in the swamps and coastal regions of the lower South. In the early months that wish had some truth, but Confederate troops fell to the same sicknesses. In fact, many joined the military already suffering recurrent malaria.

The Battle of Shiloh, fought in southwestern Tennessee on April 6-7, 1862, was the first large battle of the war. The U.S. Army of the Tennessee under Ulysses S. Grant met the Confederate Army of Mississippi up from Corinth and commanded by Albert Johnston. More men were wounded or died in this battle than in all previous American conflicts combined. Yet more soldiers succumbed to disease in the days before and after the battle than died during it.

Troops on both sides were hit by typhoid, diarrhea, scurvy and malarial fevers. A month after the battle, half of Gen. William Sherman’s 10,000 troops were still sick. The soldiers had colorful names for the diarrhea that so many suffered. Southerners called it simply “Confederate disease.” Union forces used “Virginia Quickstep” or “Tennessee Trots,” among others.

After Shiloh, Confederate troops retreated back to Corinth. They became so debilitated with diarrhea and other illnesses that they had to withdraw rather than engage pursuing Union forces. Those Union troops used the same water supply, and then experienced the “Evacuation of Corinth.”

Union efforts to capture the important Mississippi River port of Vicksburg began in the spring of 1862; the final siege ended on July 4, 1863. Union soldiers complained of “gallinippers,” the mosquitoes that were as thick as rain. Troops exploded gunpowder charges in their tents to drive them away. Grant’s troops suffered heavily from malaria during the final siege, from May 18 to July 4, 1863. The insect’s role in malaria and yellow fever would not be discovered for two decades.

History of Quinine

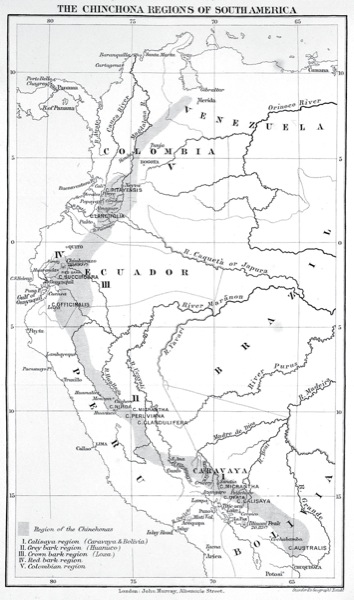

Quinine is the main alkaloid found in some members of a genus of trees and shrubs called Cinchona. These plants were originally found in western South America, especially in what is now Peru (Figure 1). By the 1570s, Spanish conquistadors understood the antifebrile usefulness of cinchona bark ground into a powder and mixed with a drink, such as wine. How the Spanish discovered this quality is disputed.

Figure 1. Map of the cinchona regions of South America.

In the 1630s, cinchona was used to treat fevers in Rome, a place that had long suffered from malarial epidemics, killing popes, cardinals and countless others. Jesuit John de Lugo, who was later named a cardinal, distributed cinchona powder among the poor of the city. In 1677, cinchona was listed in the “London Pharmacopoeia.” Quinine was finally isolated from the bark and named in 1820 by two French researchers, Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Caventou (Figure 2).

By 1850, quinine was widely used around the world to fight fevers from malaria and other diseases. A Missouri physician, John Sappington, MD, was responsible for much of its widespread use in the United States. He tried quinine on himself in 1823 and then used his slaves to manufacture pills that were sold far and wide. His book, “The Theory and Practice of Fevers,” published in 1844, included his formula and patient testimonials. The firm of Farr and Kunzie first manufactured quinine sulfate in the United States in 1823.

The alkaloid was finally synthesized in 1944, the same decade when other drugs to treat malaria were developed. Quinine remains useful today as an ingredient in tonic water (Figure 3) and a treatment for nocturnal leg cramps.

Quinine in the War

At the start of the war, physicians had few effective medicines. The “miracle” ones were morphine, ether and chloroform, and quinine. Also widely used were paregoric, a patent medicine concoction with opium for diarrhea, pain and cough; and Fowler’s solution, which contained arsenic and was used for fevers. In his 1906 article “The Use of Quinine During the Civil War,” physician John W. Churchman, MD, listed the “sinews” of that war: coffee, cathartics, ammunition, whiskey and quinine—in that order. During the war, the Union army purchased over 19 tons of quinine and 9 tons of cinchona fluid extract. By comparison, only 220,000 quarts of castor oil were purchased.

The South had trouble importing needed quinine and had no capacity to extract it from cinchona bark, even if that could have been obtained. Although some medical and other supplies got through, the Union blockade of Southern ports was very effective. Blockade inspectors found quinine in the heads of dolls and intestines of slaughtered animals. The drug could fetch $400 to $600 an ounce on the black market in the South, as demand was not only through the military but also civilians.

The South captured some medical supplies and food—the two most prized items. Opium and morphine were also only available in the South via capture or blockade running. The Union declaration of medical supplies as contraband was protested vigorously not only by the Confederacy but by some Union doctors and others on humanitarian grounds. The blockade continued.

The Confederacy had several “chemical” or drug manufacturing facilities in various states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, North and South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas. These laboratories made ether and chloroform and researched medical uses of indigenous plants.

Because of the shortage, Confederate Surgeon General Samuel Moore, MD, decided to search for quinine substitutes in the plants of Southern fields and forests. He appointed South Carolina surgeon Francis Porcher, MD, to head a survey of Southern flora for potential medical substances, especially quinine substitutes. Porcher had written his medical school thesis on botanical medicine and thus had an interest and expertise in the subject.

Porcher—with help on the manuscript from his mother and wife—produced a book in 1863, “Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests,” that is 600 pages and covers approximately 3,500 plants and trees. Moore and Porcher also published articles about possible indigenous remedies in the Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal.

Soldiers and their officers were asked to dry and forward samples to medical officers. Eventually dogwood, poplar and willow bark powdered and mixed with whiskey were chosen as substitutes. Trial and error in the field was the Confederacy’s only method of testing; Porcher had no way to conduct clinical trials himself.

Moore distributed a recipe he suggested as a tonic and “febrifuge” that included equal parts of dried dogwood, willow and poplar barks. Two pounds of these barks were to be mixed with a gallon of whiskey and steeped for two weeks. Recommended dosage was an ounce three times a day. By early summer 1864, its failure to aid in malarial fevers was apparent. Despite enormous efforts, the Confederate plan to replace quinine came to nothing.

Another problem with use of botanicals was the rejection of any such therapies by some Confederate surgeons. At that time, botanicals were associated with quack medical practitioners, despite the plant origins of many useful medicines, including quinine, digitalis, opium, belladonna and turpentine.

Turpentine, by the way, was used topically on wounds to prevent maggots and orally with castor oil for chronic diarrhea. Confederate doctors used it for fevers as a quinine substitute, a largely ineffective practice that nevertheless continued in the South until after 1900.

The Q-Call

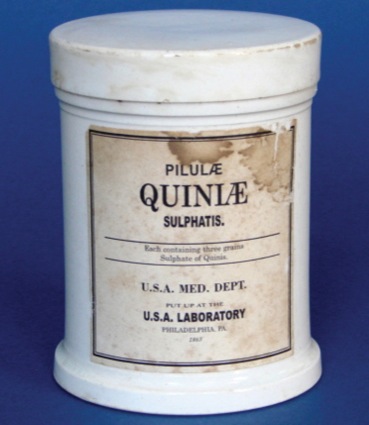

The Union had no such problem developing a supply, but the effort still had to be organized. U.S. Surgeon General William Hammond, MD, created the U.S. Army Laboratory to develop standards and ensure the purity of drug stocks obtained for the army. Hammond appointed John Michael Maisch, an immigrant from Germany, to oversee the lab, which had two locations, in Astoria, N.Y., and Philadelphia (Figure 4). Maisch also developed standard doses and the packaging and labeling of drugs for distribution to army medical depots. By war’s end, the lab had overseen production of 160 different medicines.

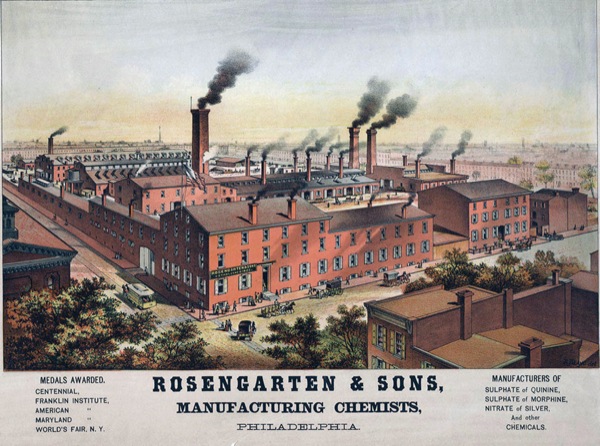

Two commercial firms, both in Philadelphia—Powers & Weightman and Zeitler & Rosengarten (Figure 5)—had been making quinine since the 1830s and manufactured it and the opium needed by the army during the Civil War. This effort—driven by the need to quickly increase stocks of quinine—created the first example of large-scale drug manufacturing and government testing in the United States.

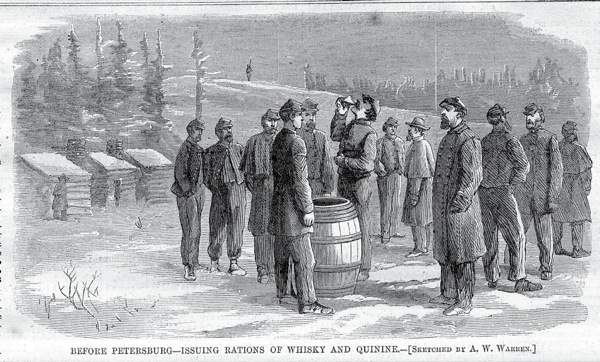

In the field, Union stewards prepared barrels of whiskey with the required amount of quinine, and each soldier took a dose every morning (Figure 6). The practice was so common in the army that songs were written about “quinine call” or “Q-call.”

Figure 6. Union troops being given their prophylactic doses of quinine and whiskey during the Petersburg Campaign, a series of battles in Virginia between June 1864 and April 1865. Andrew W. Warren was an artist from Harper’s Weekly who traveled with the Army of the Potomac during the campaign.

The quinine–whiskey combination as a prophylactic measure against malarial fevers reached a height in the Union army in the spring and summer of 1862. Woodward in his “Outlines” noted that it soon fell out of general use due to its taste, and the army largely limited quinine administration to soldiers actually showing early symptoms. Apparently some physicians kept using it prophylactically, even on themselves. “I continued to take the remedy almost continuously for two years and a half,” wrote one surgeon, “and I never discovered any unfavorable or unpleasant result from it.”

Wars often drive medical innovation, and the Civil War was no exception. Many doctors entered the conflict with little or no experience with surgery and anesthetics; that changed drastically. Medical transport was more efficiently organized using ambulances, trains and boats. Quarantine almost eliminated yellow fever. Specialty and large hospitals were constructed. Faced with shortages of such drugs as opium, anesthetics and quinine, the government and private industry cooperated to meet those needs.

The author served as a librarian in the Department of Anesthesia at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, from 1983 to 2015.

Suggested Further Reading

- Bollet AJ. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Galen Press; 2002.

- Flannery MA. Civil War Pharmacy: A History of Drugs, Drug Supply and Provision, and Therapeutics for the Union and Confederacy. Pharmaceutical Products Press; 2004.

- Jarcho S. Quinine’s Predecessor: Francesco Torti and the Early History of Cinchona. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1993.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.