Goldsboro, N.C.

On April 11, 2020, the United States celebrated a major victory. Based on public health models,1 April 11 was predicted to be the peak date for use of resources and number of new cases of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 infection (COVID-19) nationwide.

However, in most communities, this victory was not celebrated. Each region, state, county and city would face its own outbreak with varying timelines and severities. Critically ill patients with COVID-19 are presenting not only at large academic institutions with ample critical care facilities, but also at smaller community hospitals. For small- to medium-sized hospitals with limited ICU beds and ventilators, a local outbreak can quickly overwhelm available resources. Thus, it is critical for all hospitals to prepare for local surges to optimize available resources in order to prevent unnecessary loss of life from this pandemic.

Our community hospital was recently threatened with a sudden surge from multiple simultaneous outbreaks in the local community, necessitating conversion of our peri-anesthesia unit into a dedicated COVID-19 ICU. In this report, we present the details of our response, including practical considerations and lessons learned, which can be adapted by anesthesia providers throughout the country as we collectively organize and use our expertise to fight this deadly pandemic.

Setting

Wayne County, N.C., is a rural community with a population of approximately 120,000. Although rural, the presence of a local military base and state correctional facility gives Goldsboro, the county seat, a significant state presence. Wayne UNC Health Care is the local community hospital with 316 beds, 16 ICU beds with two negative-pressure ICU rooms. In the final days of March 2020, clinicians at Wayne UNC Health Care were notified of outbreaks of COVID-19 in two nearby nursing facilities and the local correctional facility. These outbreaks threatened to rapidly overwhelm the existing critical care capacity at the hospital.

However, Wayne UNC Health Care had been preparing for such an outbreak for over a month. At the beginning of March 2020, when COVID-19 cases in the United States were rapidly rising, Wayne UNC Health Care began preparing for a potential surge of critically ill COVID-19 patients. A multidisciplinary team was created to design, equip and staff a COVID-19 ICU using the hospital’s existing peri-anesthesia care unit.

Stakeholders

Conversion of the PACU into a COVID-19 ICU was a multidisciplinary endeavor, requiring input and coordination from a diverse group of stakeholders, including hospital leadership, surgical services, anesthesia, respiratory therapy, critical care, intensivists, emergency medicine, infection control, information services, medical staff, dialysis, biomed and the electronic medical record (EMR) EPIC Op-Time/Anesthesia Documentation team. Initially, this planning was completed with in-person meetings of a COVID-19 task force and designated subcommittees. As social distancing began and in-person meetings were cancelled, planning was finalized using online conferencing and necessary in-person site evaluations by individual stakeholders.

Hospital Layout/Architecture

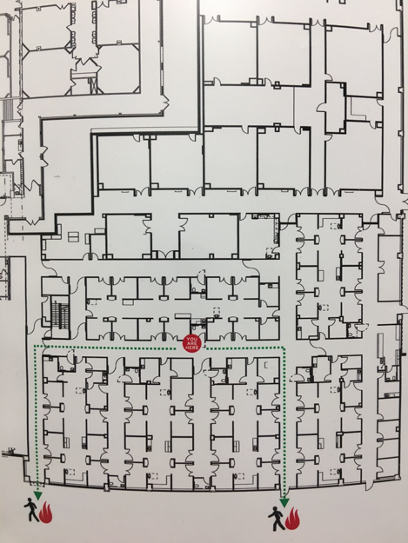

The PACU at Wayne UNC Health Care is configured as six separate pods, each with eight to 12 rooms and a central corridor (Figure 1). Each pod is separated from the others by double doors. A nursing station, medications and supplies are housed in the central corridor (Figure 2). Each room is separated from the central corridor by a curtain. This semi-isolated configuration allows for physical containment and a sequential expansion of COVID-19 ICU beds as the need arises.

Initially, one pod was dedicated to confirmed COVID-19 patients and another for patients under investigation. A total of 52 beds in the PACU could be utilized if needed. Patients being prepped and recovered from surgery are physically isolated from COVID-19 areas and, at the time of publication, had been relocated to the cardiovascular care unit, which is in close proximity to the OR.

Choice of PACU Space

The PACU had multiple advantages as a temporary COVID-19 ICU over other areas of the hospital. First, the PACU is located in close proximity to the emergency room. This allowed for direct transport of patients to the PACU from the emergency room, reducing the possibility of contamination to non-COVID-19 patients or staff. Second, the PACU is isolated from other patient units in the hospital, again minimizing the likelihood of spread to non-COVID-19 patients and staff. Third, each PACU bay has air, oxygen and suction connections, allowing operation of both ICU ventilators and anesthesia machines as well as suctioning of ventilated patients. Finally, PACU bays were deemed to be superior to ORs due to the large amount of equipment and supplies traditionally stored in ORs, which would have necessitated removal, disinfection or disposal if used for treatment of COVID-19-positive patients.

However, conversion of PACU bays also presented many challenges. First, the PACU bays are not negative-pressure rooms and do not have anterooms, with the exception of the two negative-pressure rooms located within the unit. Second, there are no water lines in the PACU bays, which would create problems for patients requiring hemodialysis. Finally, bays are significantly smaller than rooms traditionally used for critical care, resulting in space constraints, particularly when an anesthesia machine, infusion pumps and a full-sized hospital bed are placed in the room.

Personnel

Following the reduction of daily surgical cases to emergent and urgent cases only, the PACU staff was redeployed to cross-train in the ICU. Personnel considered high risk (age >65 years, those with preexisting medical conditions or who were pregnant) were allowed to self-exclude from the COVID-19 ICU. Medical management of patients is directed by a critical care intensivist. Intubations, line placement and management of anesthesia machines are performed by nurse anesthetists and anesthesiologists. Bedside nursing care is split between traditional ICU nurses and the redeployed PACU nurses employing a team nursing model. ICU ventilators are managed by respiratory therapists.

Infection Prevention

While each pod is physically separated by hallways and doors from other units, individual rooms within a pod are separated from the central corridor by curtains. Each pod has a central ventilation system, and airflow was increased to maximize air turnover and create a negative-pressure unit. Following CDC guidelines on personal protective equipment (PPE),2,3 health care providers would don an N95 face shield or powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) in the hallway outside each COVID-19 pod before entering the corridor. N95 masks and eye protection would be kept on the entire time personnel were in the COVID-19 pod. Gowns and gloves would be donned before and after each patient encounter, with appropriate hand hygiene. When exiting the pod, gowns and gloves are first removed with appropriate hand hygiene. The N95 with face shield or PAPR are not removed until personnel have exited into the hallway outside the COVID-19 pod and performed hand hygiene.

A code cart, intubation cart with difficult airway equipment including video laryngoscopy and surgical airway, and invasive monitoring equipment were immediately accessible to each pod. Additionally, resources on COVID-19 patient management and ventilation were printed and placed in binders within each pod corridor for quick access by all personnel.

Ventilation

Patients with confirmed COVID-19 requiring mechanical ventilation were intubated by CRNAs, following Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) intubation guidelines for COVID-19 patients.4,5 Patients were then ventilated using Dräger Apollo anesthesia machines (Figures 3 and 4). These ventilators were managed by CRNAs according to APSF guidelines for using anesthesia machines for critical care ventilation.4 Ventilation modifications by critical care intensivists were based on arterial blood gas analysis, patient oxygenation and end-tidal carbon dioxide (etCO2). To reduce risk for medication error or contamination of rooms with volatile anesthetics (scavenging systems for anesthesia machines were not used), vaporizers were removed from the anesthesia machines. Viral filters were placed at the inspiratory and expiratory limbs of the circuit, as well as at the endotracheal tube near the patient (Figures 5 and 6). Fresh gas flow was kept near the patient’s minute ventilation to reduce condensation accumulation, and CO2 absorbers were replaced frequently.

Electronic Medical Record and Administrative Considerations

Temporary conversion of the PACU to an inpatient unit presented challenges involving admission and documentation. The PACU is not traditionally a unit that can be used for admissions, so our information services department created a virtual unit in our EMR system. When an anesthesia machine is used as a ventilator, the monitor associated with the machine is also used to track vital signs. To enable the anesthesia machine data to flow into the EMR, representatives from BioMed first made configuration changes to the monitors. Once made, the information services department reconfigured the devices to include anesthesia machine vitals to be passed to the patient’s EMR. This allowed personnel to associate the devices with the patients in the room and capture not only the ventilator data but the vitals from the patient’s monitor, as well.

Conclusion

At the time of publication, patients are currently receiving critical care within the newly designated COVID-19 ICU. By quickly organizing and creating a dedicated unit isolated from other units in the hospital and by using anesthesia machines as ventilators, critical care capacity at Wayne UNC Health Care was nearly tripled. It is our goal that other community hospitals will be empowered during this crisis and use our example as a template for their own response. Each hospital is unique and will face different obstacles in combating this virus, but this design can be implemented to varying degrees in many community hospitals during this COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- Murray. 2020. Forecasting COVID-19 impact on hospital bed-days, ICU-days, ventilator-days and deaths by US state in the next 4 months. medRxiv 2020.03.27.20043752. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.27.20043752

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/A_FS_HCP_COVID19_PPE.pdf

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesia machines as ventilators. www.asahq.org/in-the-spotlight/coronavirus-covid-19-information/

- Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. www.apsf.org/news-updates/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.